‘Terror Camp’ Could Be a Glimpse of the Future of Fandom and Scholarship

“It’s academia that feels criminally fun!”

When Hester Blum signed up for Terror Camp, she didn’t know quite what to expect.

A professor of English at Penn State University, Blum had been doing work on the polar humanities, an interdisciplinary speciality focused on the Arctic and Antarctic. “I started following anyone who was tweeting about polar regions,” she says. “And especially about historical polar expeditions.” When she saw several people she follows mention Terror Camp—apparently connected to a doomed polar expedition in the 1840s and a television show about it—she was intrigued. “I took a look and couldn’t quite, at first, tell—is this a fan conference? Who’s involved in this?”

The two-day virtual event was held on a weekend in mid-December 2023. Similar gatherings for another of her specialties, Melville and Moby-Dick, tended to be “mostly be 60-year-old white men with beards,” so she was expecting a similar demographic when she logged on. “So when it was all people in their 20s who are nonbinary, it was this incredible sense of an exploding world of options and possibilities for thinking about these topics,” she says. She describes the event—a cocktail of academic history and pop-culture fandom—as “transformative.” The passion and intelligence of its largely younger attendees, she thought, “could save the humanities.”

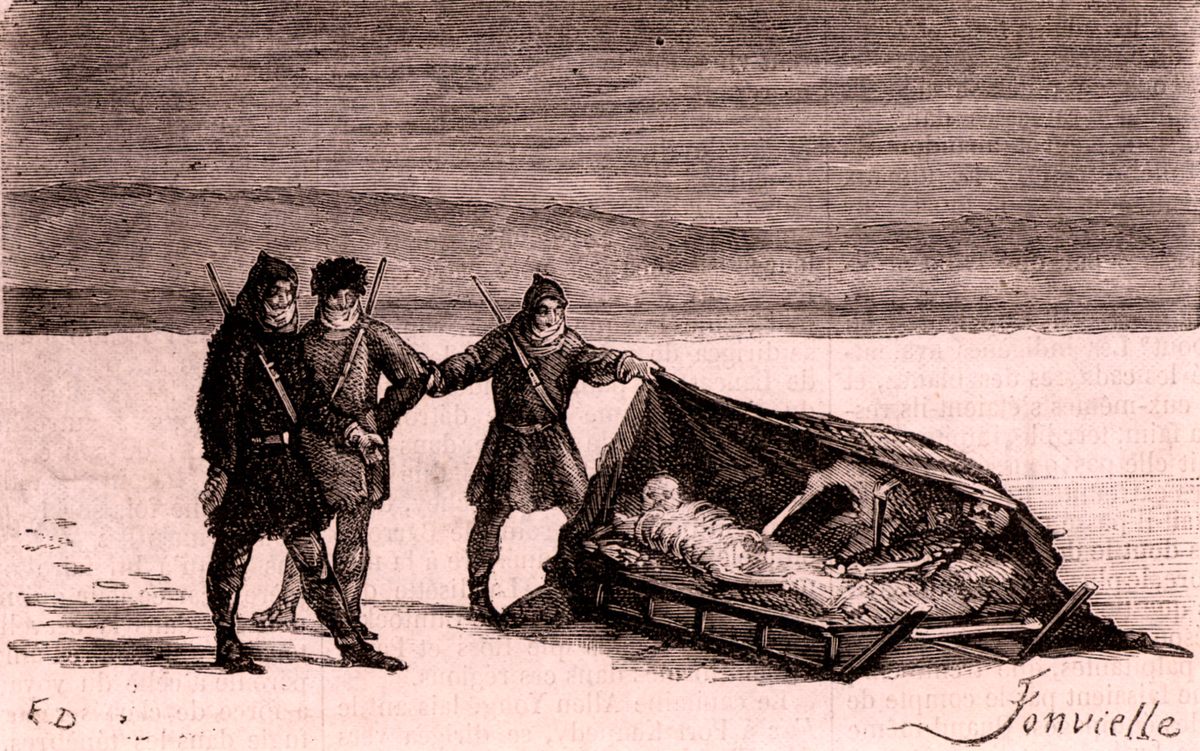

Terror Camp is, at its core, a fan conference centered around the first season of the 2018–19 AMC television series The Terror. It is based on a 2007 novel of the same name by Dan Simmons, a fictionalized account of the ill-fated mission to navigate the Northwest Passage led by Sir John Franklin in the late 1840s. The two ships on the expedition, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, became locked in ice for over a year, and all hands were eventually lost. The event focusing on the show was originally conceived by Allegra Rosenberg, author of the forthcoming Fandom Forever (And Ever) on the history of fan culture—and a member of what she describes as the “small but very passionate fandom” for The Terror.

Rosenberg had first tried to put together a Zoom event with the show’s actors during the early days of the pandemic, but it didn’t pan out. But, like many of her fellow fans, a deep interest in the show—which was fictionalized but based on extensive research—had also led her to a deep interest in polar history. The following year, she noticed a few polar academics were talking about organizing an event to showcase their work for other fans of the show. “I jumped into that conversation and said, ‘That sounds like a cool idea,’” Rosenberg says. “‘Maybe we can combine it with my idea about getting the actors to come talk to us.’”

The result was Terror Camp, where fans go deep on their historical fascination, academics get to share work with a truly devoted audience, and presenters and attendees alike comfortably straddle both worlds. The first conference was a single-day event capped off by a keynote from The Terror showrunner Dave Kajganich; in 2022, it expanded to two days, and mixed interviews with the cast and crew with academic presentations.

And in its third year in December 2023, the event widened its scope even further, splitting the two days between the two poles—Terror Day for the Arctic and Erebus Day for the Antarctic. (The Franklin expedition ships, before being lost in the Arctic, had also journeyed together to Antarctica, and now lend their names to a pair of mountains there.) Year over year, the number of attendees has steadily grown; in 2023, Terror Camp saw more than 900 RSVPs.

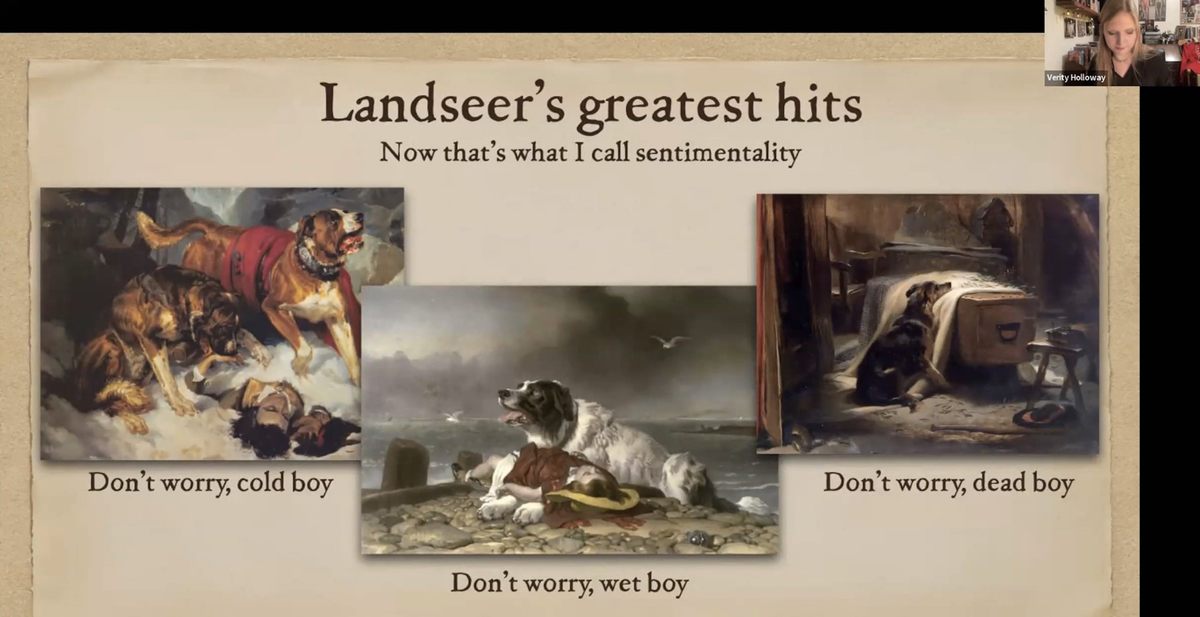

Fan conventions, virtual and in person, have long hosted scholars, and there are, of course, entire subfields of academia that examine pop-culture texts and their audiences. But in its evolution, Terror Camp has become a true hybrid. “We have an artist’s alley, as if we’re a fan convention, but we have a poster alley as if we’re an academic conference,” says Rosenberg. “It’s about taking the best of both of these worlds—the fan con and the academic conference—and putting it into a virtual environment that gives people the opportunity not only to learn, but to express excitement and passion and enthusiasm about what they’re learning, all these emotional states that are sort of looked down upon within the actual academy.”

Johannes, one of the event’s founding moderators, jokes that when they were initially planning Terror Camp, he’d written, “I wouldn’t want to do anything huge, just a low-stakes, low-effort academia LARP [live-action roleplay].” A political scientist working on gender and nationalism, he’d used that lens to analyze The Terror—and his writing in fandom fed back into his academic research. These kinds of intersections—like encouraging fans to present “meta,” an umbrella term for fannish nonfiction writing—are at the heart of the event, which lets participants engage in serious analysis simply because a topic interests them. “To me, giving space to something that is ‘self-indulgent’ is still one of the greatest aspects of Terror Camp,” he says. “It’s academia that feels criminally fun!”

Emma Johanna Puranen, who spoke at this year’s conference, is an academic in another field, or rather, fields. She describes herself as “too interdisciplinary to function;” she uses data science to look at the portrayal of exoplanets in science fiction. She came to Terror Camp via an interest in polar history—she’s even written a LARP reenacting the Discovery Expedition, the early Antarctic mission that brought together upcoming stars of the polar exploration world, including Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. She brought her PhD research into her Terror Camp presentation, “From the South Pole to the Stars,” which she says prompted “really incisive audience questions that made great connections,” such as comparisons between Starfleet in Star Trek and early polar expeditions.

By contrast, Marv, a marketing associate, first came to Terror Camp in 2022 after discovering the show via fanart. Like many attendees, an interest in the fictional led to an interest in the historical. This past year, he presented a poster entitled “A Reliable and Careful Servant: Edmund Hoar,” on one of the show’s minor characters—who was, of course, a real person on the Franklin Expedition. “One of my main takeaways from Terror Camp 2022 had been the devotion of this community to uplifting and engaging with memories of the dead,” he says. “And appreciating the complexities involved in the acts of remembering and presenting information.” By the time he was creating his poster, he was “emailing a dead man’s great-great-great-grand-nephew about the tattoo he had, hoping to share a bit of this real person’s story with the world.”

For Hester Blum, tuning in to Terror Camp and seeing the enthusiasm for her own field was astounding. “In academic circles, there aren’t many superfans of polar exploration,” she says. “I think for anyone in academia, no matter what you work on, the idea that there are hundreds of people in their 20s or early 30s who are passionately interested in your topic is unthinkable.”

Watching the presentations from younger fans also made her reassess the way she and her colleagues approach their students; many academics discuss younger generations’ interest in “relatability,” and how it prevents them from engaging with history and literature. “One of the things that this conference made me realize is how fundamentally we have misunderstood what it means to be ‘relatable,’” she says. “And it’s not simply a lack of critical distance or affinity—but the kind of passionate fan response, as something that is deeply critical and deeply thought-through. It was one of those moments that was like, ‘Oh, this can be the future of engagement.’ This was incredible.”

Academic structures don’t often leave space for this kind of unbridled fannishness—despite the fact that academics might be fans themselves, or fans in all but name. “I think there is perhaps a fear or wariness among academics that fans cannot do discerning research, that they are too clouded by their emotions,” Puranen says. “But I would argue that anybody doing a PhD in a field must be obsessed with it.” Johannes echoed those sentiments. “I do think there’s something deeply fannish about writing a dissertation, at least for some of us,” he says. “The impulse to learn more about my research topic, my case, my methodology feels very similar to rotating my blorbos in my head, if you’ll permit the Tumblr-ism.” (He’s using the Tumblr term for a favorite character.) And for Marv, who dropped out of a graduate program five years ago, being given the space to be enthusiastic about research has him actively applying again. “By situating scholarly research and fandom alongside one another, Terror Camp gave me the spark I needed to feel capable of participating in both of those communities, both of which I’d been feeling alienated from,” he says.

Even though the scope is now far wider than the initial idea to Zoom with some actors—and even though attendees now have many different routes into the event—for Rosenberg, Terror Camp all comes back to The Terror, and how the deep historical research that underpins it actually inspires creativity. “It sort of wakes people up like a sleeper agent,” she says. “And through that fannish mode, to be able to be like, ‘Oh, I think I care about history now. I think I want to do what the show did. I want to be more like Dave [Kajganich] and Soo Hugh, the other showrunner, and go back to this history and find the creative potential in that, just like they did.’ It’s almost like leading by example.”

Whether it’s giving academics permission to be fannish, or making space for fans in the academy, Terror Camp is breaking down barriers. “I think it’s a sort of parable of the persistence of emotion, of affect, of joy—and that’s why it’s so important to bring that to the public,” Rosenberg says. “I want to show people who maybe haven’t had exposure to this way of working the potential that this sort of fannish mode has in terms of real, legitimate research and discovery.” And for fans, she hopes to keep making space for anyone who, in her words, “catches the bug.”

“It’s such a powerful agent of obsession,” she says. “And you find that that feeling can and does persist—and that you can get just as much joy out of trawling through the British newspaper online archives, looking for peoples’ names, as you can scrolling through gifsets on Tumblr.”

Elizabeth Minkel has written about fans and fandom for WIRED, The Guardian, The New Yorker, New Statesman, and many other publications. She’s cohost of the Fansplaining podcast and co-curates the Hugo-finalist newsletter “The Rec Center.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook