The Unexpected Origins of Fecal Transplants: Termites

Termites. (Photo: Bernard DuPont/flickr)

What do termites and fecal implants have in common? It turns out that the little bugs are the unsung innovators in an increasingly popular medical procedure.

Also known by the more scientific-sounding term fecal microbiota transplantation, the practice refers to placing stool from one person into another person. The goal is for recipients to become imbued with healthy gut bacteria, whom are critical endosymbionts in our bodies for efficient digestion. Fecal transplants recently became popular with people suffering from Clostridium difficile infections, a serious and hard to treat health condition. Clostridium infections are estimated to affect dozens of thousands of people each year, killing many of them. For the afflicted, fecal transplants have been a literal life-saver.

Clostridium difficile colonies. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Yet they are also now being promoted as an all-around holistic health practice to combat “dysbiosis,” a perceived imbalance of microbes within the body. This has given rise to the practice of DIY fecal implants, a practice was considered fringe, but has gone mainstream in recent years, with clinics all over the United States and Europe offering this service. Some people are now even debating saving the stool of their pure newborns, in case they need them as defiled adults. As further evidence of its accepted status as a mainstream medical practice, in 2013 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration decided to regulate fecal transplants.

But don’t let the newly formed tech start up or plethora of DIY websites with step-by-step instructions devoted to them fool you. Fecal transplants are nothing new.

And they are most definitely not evidence of human invention and ingenuity. Termites invented them, 251 million years ago.

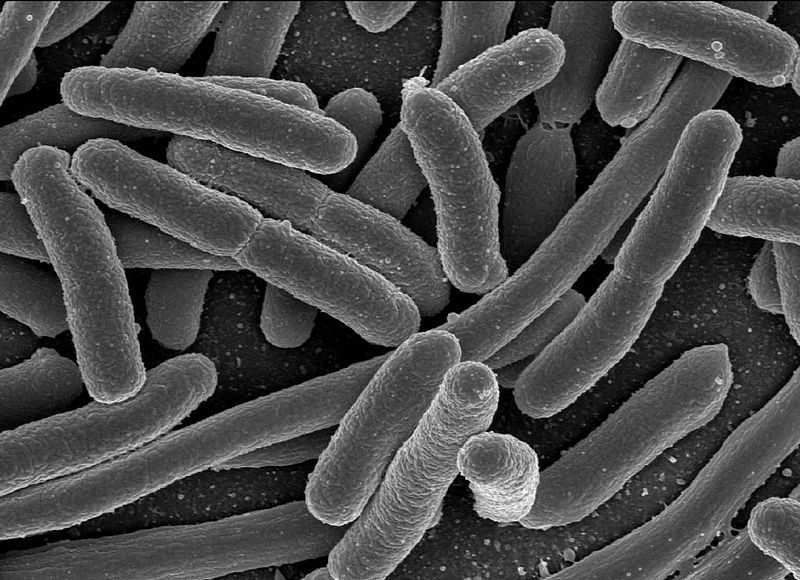

Escherichia coli, one of the many species of bacteria present in the human gut. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Previous accounts have traced the origins of fecal transplants to a journal report from the U.S. in 1958 or ancient Chinese documents from 1700 years ago. But they’re wrong. Termites routinely use this practice. They’re either the original uncredited inspiration for our current craze – or we overlooked an organism we could learn a lot from.

“Termites feed on wood and other plant materials,” says Patrick Liesch, extension entomologist of the Insect Diagnostic Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, “The main ingredient is cellulose, and cellulose is tough for animals to break down.” He has a good point—how edible does a tree look to you? According to Liesch, termites are in a “unique situation” because their gut biome has microbial symbionts, like protozoa and bacteria. Termites ingest the cellulose and when it gets to their guts, the microbes break it down into molecules that can be used by the insect.

Trophallaxis in a weaver ant. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

What does this have to do with fecal transplants? Termites, like many other insects, molt, shedding their outer layer. “When insects molt and shed their exoskeleton, they are actually losing parts of their digestive tract,” Liesch said. “In doing this, they lose their gut symbionts.” This is because termites have their gut bacteria in their midgut, deeper into their digestion tract, unlike other insects, which have gut bacteria in their hindgut. Fecal transplants are a key way that termites are able to get those crucial bacteria back and continue to successfully digest food.

“It’s called trophallaxis,” says Rachel Arango, an entomologist and student trainee with the USDA Forest Service. “Termites will feed mouth to anus; it’s very common and the best way to get their gut symbionts back.” Trophollaxis can also be performed mouth to mouth, as some life stages of termites, like soldiers and reproductive, cannot feed themselves. She’s also seen them resort to more unconventional methods to obtain their needed gut bacteria. “Sometimes they will eat the entire abdomen of another worker or their own discarded exoskeleton,” she added.

Termites in action. (Photo: Aleksey Gnilenkov/flickr)

Arango isn’t merely interested in understanding termite gut bacteria though; she’s interested in the implications and applications for human health. Human gut flora has become a cultural obsession of late: Multiple research groups have sequenced the meta-genome of the community of bacteria living in humans’ digestive tracts. We’ve learned that most of the cells in our body are bacterial, not human. Now our intestinal bacteria have been credited (blamed?) with everything from obesity to brain function.

“Many termites live in the soil, surrounded by pathogenic mold and bacteria—and yet they don’t get sick,” she says. “I’m interested in the antibodies they produce with their gut symbionts. By understanding how the termites defend themselves, we can potentially identify natural properties and potentially use them against human pathogens.” Insights from termites may help us humans understand even more about our nature. “Sharing gut bacteria is thought to help termites recognize their nest-mates and cooperate socially,” Arango added. Maybe sharing stool will live up to the hype after all.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook