The WWI Plan To Turn America’s Trees Into Telephones

George O. Squier’s Floraphone was set to transform the country’s forests into communication hubs—until it didn’t.

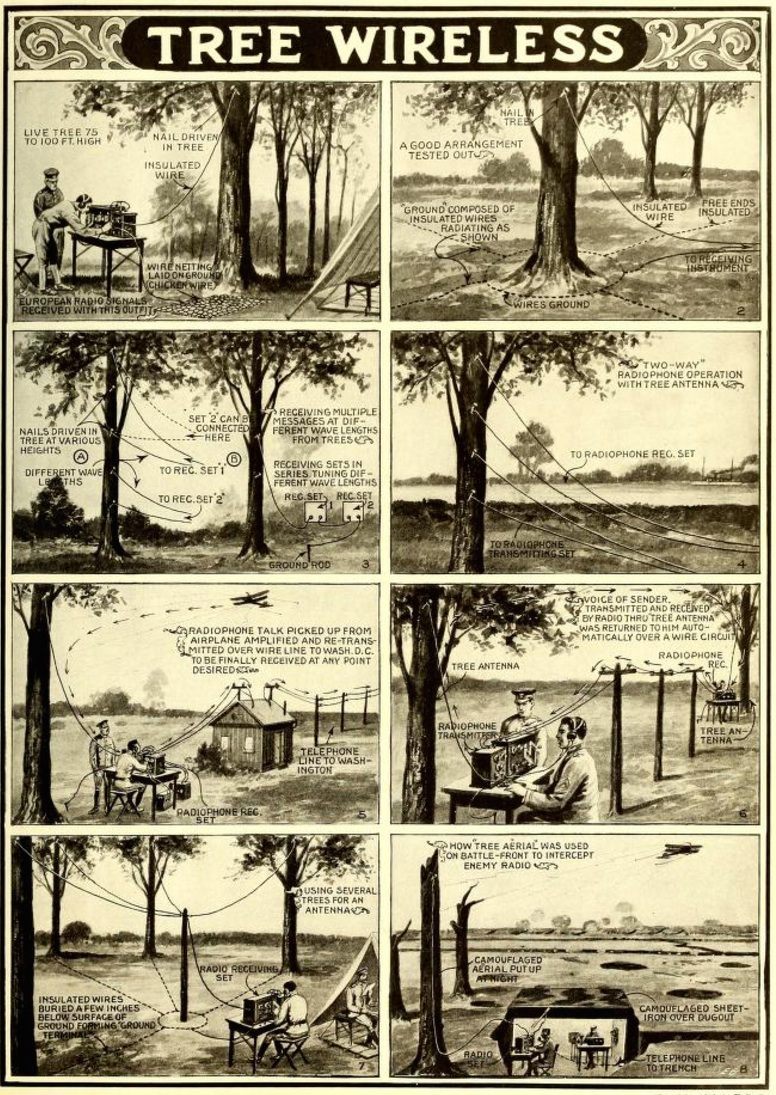

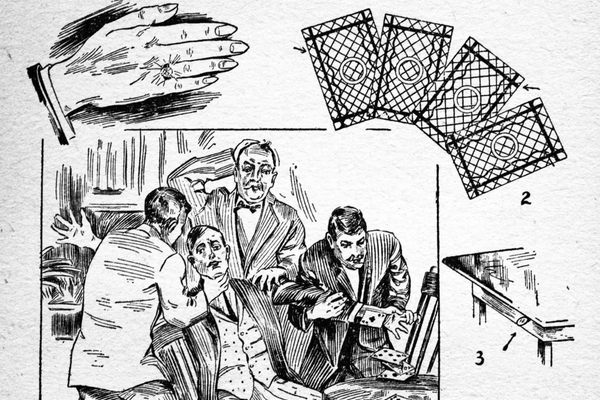

A step-by-step guide to floraphoning your tree. (Image: Smithsonian Libraries/July 1919 “Electrical Experimenter”/Public Domain)

Every late-night park walker has been through it. You’re lost in thought, passing beneath a line of trees, when you hear a distinct rustle. It’s no ordinary rustle—it seems to have tone, diction, syntax. You pause: did that maple just say something? Then you shake your head and move on.

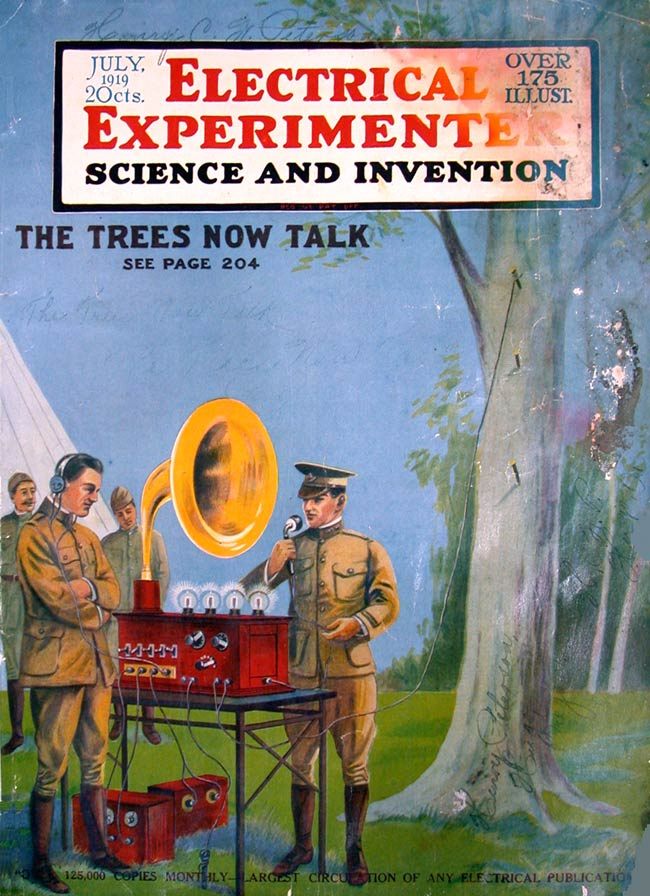

In the early 1900s, though, you might have been right. For a brief period at the beginning of the 20th century, America’s trees didn’t just talk—they intercepted enemy intelligence, beamed political speeches to the far-flung populace, and tuned into baseball games. Someday, it was thought, they’d transform everything from military strategy to media broadcasting. In a growing country that wanted nothing more than to be connected, the great green hope of instant contact lay with Major General George O. Squier’s unassuming, super-economical floraphone.

Squier was a short, redheaded Duluth, Minnesota native who somehow transformed a distaste for authority into an astoundingly successful military career. He was also the early 20th century’s go-to guy for ideas so crazy, they just might work. The first American West Point graduate to also hold a Ph.D. (from Johns Hopkins University, in electrical engineering), he dedicated his entire adulthood to zapping life into otherwise straitlaced institutions. He developed remote-control cannons, and convinced the army to add an aviation unit. Late in his life, he invented Muzak. As a 1922 Boy’s Life profile put it, “When people say that ‘it can’t be done,’ General Squier is inspired to do his best.”

George O. Squier’s floraphone, illustrated on the cover of July 1919’s “Electrical Experimenter.” (Image: Smithsonian Libraries/Public Domain)

In 1904, Squier was stationed at Camp Atascadero in California. It was a particularly hot, dry summer, and the soldiers’ Army-issued buzzer telegraph and telephone kits, which relied on moisture to receive and transmit signals, were pretty much useless. Squier quickly grew tired of being stranded out in the field, cut off from everyone, so he mixed his engineering skills with his military instincts and started tinkering with the resources he had available.

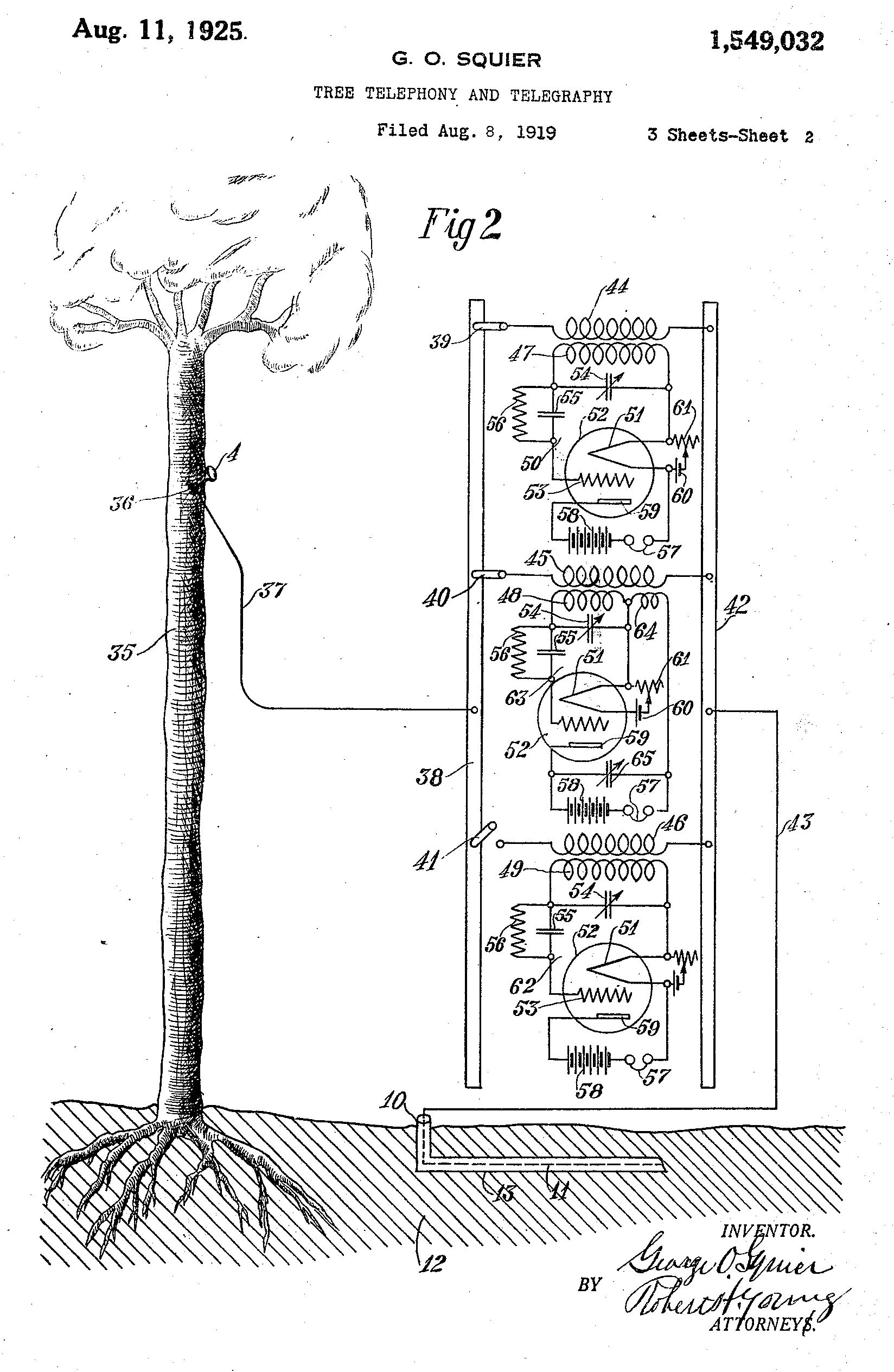

Soon, he hit on a simple fix: wire the kits to a nearby eucalyptus tree, and the messages come through fine. Further experimentation revealed the best configuration: a long, insulated wire, nailed two-thirds of the way up the trunk, attached to a receiver and grounded by a few more wires buried in a radial configuration around the roots. “[Squier] has found that trees may serve the purpose of Marconi’s metal feelers or antennae, as they are called,” reported The Search-Light in August 1905, adding that Squier had successfully used his innovation to send messages “between Goat and Alcatraz Islands, a distance of three miles and a half.”

Squier obtained a patent for “Tree Telephony and Telegraphy” in 1905, noting that the use of trees would drastically cut down on aerial costs. (He would later come up with a catchier brand name—the “floraphone.”) But he was a busy man, and it took another decade before he would revisit the arboreal antenna.

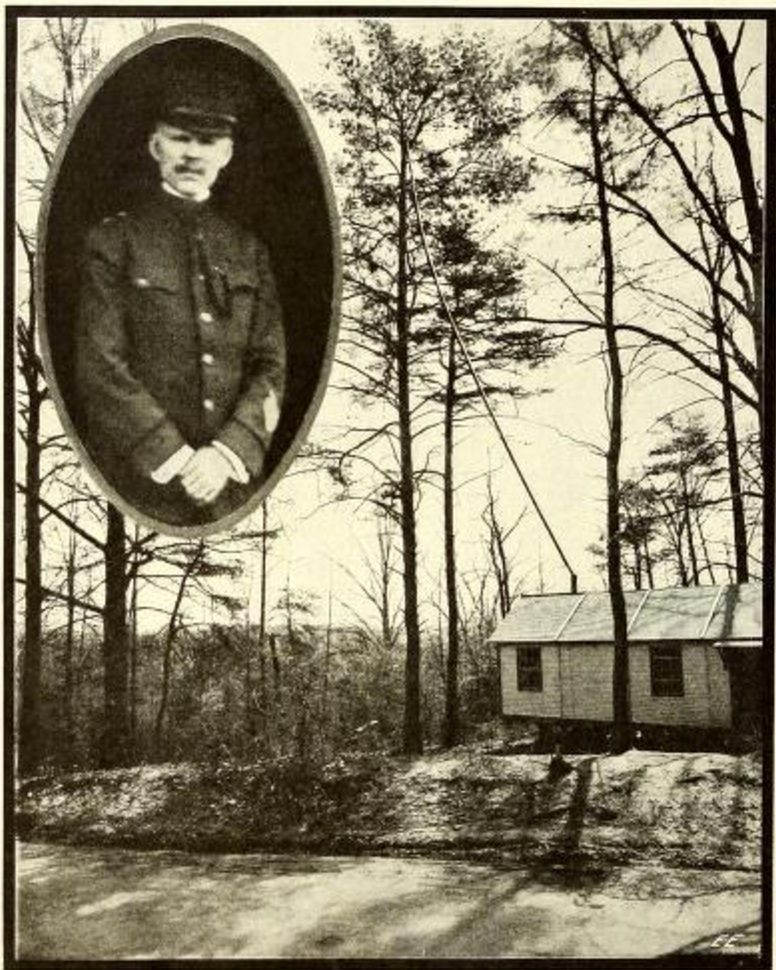

Major General George O. Squier, and the portable house he experimented out of (note the hooked-up oak). (Image: Smithsonian Libraries/Public Domain)

By this time, World War I was in full swing, and the U.S. military was looking for a large-scale backup communication system in case its submarine cables failed. Squier, now the Chief Officer of the US Army Signal Corps, decided to put the country’s trees to the test.

He set up an experimental station in the woods outside of Washington, D.C.—a small portable house manned by a few soldiers at a time, equipped with amplifiers and receivers and surrounded by acres upon acres of potential antennae. In July of 1919, Scientific American sent a writer to check it out. The soldier on duty hooked up a nearby oak, twiddled the knobs, and handed over the headphones. There was static—and then, suddenly, German. Messages were streaming from the giant antennae of Nauen Transmitter Station in Brandenburg, pulsing through the air for over 4,000 miles, and getting pulled back down to earth by this humble D.C. oak.

The soldier went outside, switched to a pine, and began surfing channels: dispatches from Lyon, from Cornwall’s Poldhu station, from mid-Atlantic ships, and from the incoming NC-4 transatlantic plane all came through cleanly. “It is not a joke nor a scientific curiosity,” the reporter concluded, breathlessly, “Trees—all trees, of all kinds and all heights, growing anywhere—are nature’s own wireless towers and antenna combined.”

An illustration from Squier’s 1919 Floraphone patent. (Image: George O. Squier/Public Domain)

Devotees let their imaginations branch wildly. Scientific American’s correspondent described soldiers armed to the teeth with nature’s communicative potential, a carrier pigeon in one hand and a tree wireless set in the other. In such a world, he extrapolated, whole forests posed a Macbethian military threat: “The armies of the future (if there be such) will in action consider all trees as dangerous enemy aerial stations,” he wrote.

Others were more interested in peacetime applications. A Popular Science reporter predicted a new era of connectivity, in which floraphone stations could be used to keep up with international news and sports scores, and everyone from rural farmers to lost pilots could make quick human contact, provided they were “in the neighborhood of a good-sized tree.” In August of 1919, in an attempt to broadcast a Vice Presidential address to as many nearby homes as possible, “several large trees [were] equipped with Gen. Squir’s florophone,” the Washington Post reported.

Despite such triumphs, the floraphone’s heyday was short-lived. Quickly outpaced by more portable and effective antennae, it now lives alongside bat bombs, iceberg airbases, and artichoke ink in the annals of war technology made goofy with time. The technology remains solid, and the idea is occasionally resurrected by jungle platoons, ham radio enthusiasts, and eco-art collectives. Something of its aesthetic echo can be found in the laughable camouflage of those gargantuan cell phone towers certain companies try to pass off as trees.

Tree antenna testing for #ageofwonder with Bioartlabs pic.twitter.com/aD4llL6JV7

— Baltan Laboratories (@baltanlab) March 23, 2014

These days, though—as we grapple with the fact that our ability to transmit words, thoughts and information at near-instantaneous speeds doesn’t necessarily make us feel any less lonely—it might be a good time to revisit the floraphone, whose appeal, as Squier knew, was not merely technological. “All through the ages there is shown in literature a feeling of reverence, sympathy and human intimacy with trees,” he wrote in 1919. “It is significant that this practical thing possessing utility and natural strength, architectural beauty of design, and endurance far superior to artificial structures prepared by man, should be able yet further to minister to his needs.” Next time you want to call in a takeout order or catch the Mets, you may want to consider looping in a tree.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook