Until WWII, Americans in China Had Their Own Special Expat Courts

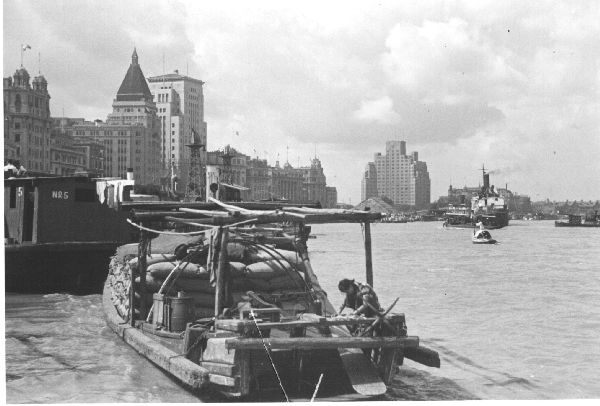

The Bund, Shanghai, 1928. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

On July 2, 1937, a 20-year-old Stanford student visited Shanghai after a year studying abroad in southern China. Curious about the “judiciary complications that would naturally ensue from such a mixed-up city,” Melville Jacoby was looking forward to visiting the chambers of Judge Milton J. Helmick, who presided over a peculiar but powerful instrument of early 20th century American colonialism: the United States Court for China.

Yes, the United States had its own court of law in China.

What neither Jacoby nor Helmick knew was that he would be the last judge to preside over the court. Five days after Jacoby’s visit, Japan and China would exchange the first shots of a conflict that would morph into World War II and ultimately see the end of extraterritoriality.

For decades, the U.S., like Great Britain, France, Japan and a handful of other countries, had enjoyed extensive “extraterritorial” powers in China. Since 1906, the court had been part of these powers. This meant that U.S. citizens in China were subject to American, not Chinese law, even when on Chinese soil. If an American were accused of a crime or sued anywhere in China, Helmick or one of his four predecessors, not a Chinese judge, would have heard her case.

Judge Helmick, appointed by FDR in 1934 and formerly New Mexico’s attorney general, joked that anyone qualified enough to preside over the court “would surely have proved too sagacious to take the job.” In an ordinary day, a judge in his position, Helmick wrote:

“ought to have known most of the substantive law there is on any subject, Federal procedure and practice, state court methods and function, all about extraterritoriality, a little international law, a smattering of the laws of other countries, something of Chinese law, a great deal about China, a lot about international politics, considerable about diplomatic usages, a bit of anthropology and a modicum about bomb dodging. Curiously, he need not know that elusive thing called the Chinese language.”

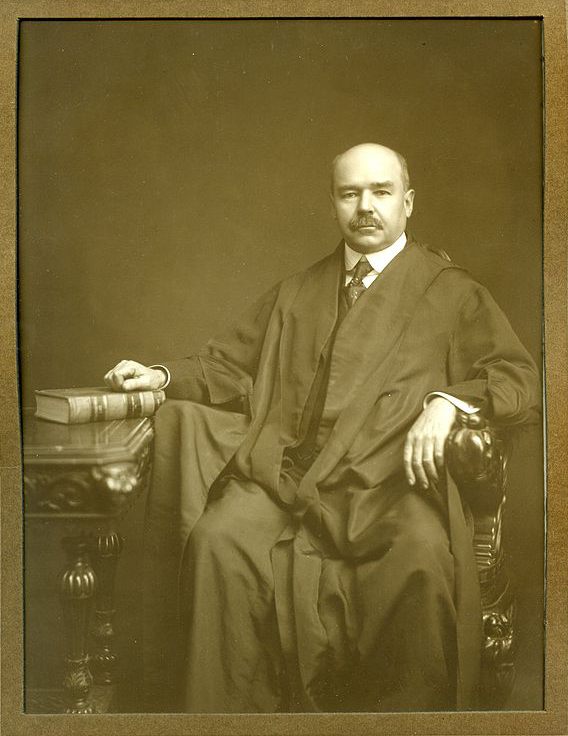

Portrait of Charles S. Lobingier, in judicial robes, c. 1920, a judge of the US Court for China. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

As Jacoby wrote out in a letter to his family after meeting Helmick, one of the Judge’s chief difficulties was figuring out which laws even applied in China. It was unclear whether the United States Court for China was a federal court, a local court, a state or territorial enterprise, or a consular court.

“Obviously–or perhaps not?–China was not a ‘state’ of the United States,” writes Emory University Law Professor Teemu Ruskola. “In the end the only thing truly obvious was that the court was sui generis.”

The 1907 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Decision Biddle v. United States, said that any federal law that applied in any part of the United States could be applied in China. At first, the federal territory in Alaska seemed like the best model, but then the court leaned toward the District of Columbia code to guide its decisions.

“Consequently every American lawyer in China had a D.C. Code on his desk for his number-one law book, just as any lawyer in America would have his own state statutes on his desk,” Helmick wrote in a 1941 article. “American Law” in China on just about every matter, from traffic violations to wrongful death suits came from Washington D.C., though judges tended to interpret the application of D.C. code as it fit China.

“It is odd when you see cases like ‘so and so was brought up for pushing a Chinese into the Huangpu River contrary to the laws of the District of Columbia,” says Eileen Scully, a professor at Bennington College whose book, Bargaining with the State from Afar: American Citizenship in Treaty Port China, deals extensively with the court.

Shanghai harbor in 1937, the year of the Battle of Shanghai. (Photo: SDASM Archives/flickr)

One thing was definitive about the United States Court for China, though. There were no juries. Trials were decided by judges, though a court commissioner handled traffic citations. Only Americans could be tried or sued by the court, though anyone could be a plaintiff. Moreover, non-American witnesses could not be compelled to answer questions, as they weren’t subject to contempt.

For a court with so much power, the U.S. Court for China was little known, even during its time. “It seemed that Congress had to be reminded that the court existed,” says Scully.

Complicating matters yet further, few litigants ever appealed cases heard by the U.S. Court for China. Appeals were heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which sat in faraway San Francisco, and it could take two to three years from the original decision for Ninth Circuit judges to render a new decision. The Ninth Circuit heard only about two appeals a year from the China court, and most of the judgments in those appeals were affirmed.

Even in China, logistics proved a problem. The United States Court for China had the largest jurisdiction of any U.S. court in terms of land area. Though the court’s judges were based in Shanghai, they also sat annually in Tianjin (about 600 miles north of Shanghai), Hankou (about 430 miles west), and Guangzhou (765 miles to the southwest). These were huge distances to travel at a time when China still lacked extensive infrastructure, especially early in the court’s tenure.

“Except for absence of jury trials, the Bill of Rights is otherwise scrupulously respected as a matter of primary American principle and legal policy,” Helmick wrote in 1941. Defendants’ rights to speedy trials were also constrained; sometimes, accused criminals were held for many months before being tried.

“When I first started looking into it I was expecting the court to be kind of a kangaroo court,” admits Scully. Instead, she says, the court was often used as a model of American democracy by progressive-era politicians interested in nation building in China. This was particularly true for the court’s first judge, Lebbeus R. Wilfley, and its third judge, Charles Loebinger, who presided from 1914 to 1924 and often used his position on the bench to advance his own agenda. “He was very good at making this a showcase of Chinese justice,” says Scully.

Zhang Zongchan, a warlord with close ties to Leonard Husar, the U.S. District Attorney for China . (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Not everyone involved with the court portrayed the U.S. positively. During the 1920s, Leonard Husar, the U.S. District Attorney for China–the government’s chief prosecutor in China–ran guns to a powerful warlord named Zhang Zongchang, who also paid him to assist an opium smuggling ring. Husar was finally convicted in 1927 for extorting prostitutes and accepting bribes from Zhang.

Dramatic as Husar’s downfall may have been, most of the cases heard by the U.S. Court for China were decidedly dull. In the 1920s, China was wracked in civil strife as warlords vied for control of the country. But extraterritoriality meant Shanghai (and to a lesser extent, other treaty ports) was a bubble where Americans just wanted to collect their rent or seek damages for a business deal gone sour.

“This was kind of the point,” Scully explains. “They allowed people to have everyday lives while China is falling apart.”

Helmick served as the court’s judge until Japan seized control of Shanghai following its attack on Pearl Harbor. Detained for months with a number of other Americans at Shanghai’s Hotel Metropole, Helmick was finally repatriated to the United States on one of two trips of the Gripsholm, a neutral Swedish vessel used for prisoner exchanges throughout the war.

The Flying Tigers, a volunteer air force in China. (Photo: SDASM Archives/flickr)

The last case the U.S. Court for China ever heard involved a different extension of U.S. power in China: the Flying Tigers, a volunteer air force led by General Claire Chennault.

One night in April, 1942, Chennault’s right hand man, Boatner Carney, a balding flying instructor with a push-broom mustache, shot and killed another soldier, William Reichmann, after a bar fight in southwestern China. Carney’s case was rushed before the court because the U.S. had signed but not ratified a treaty to end extraterritoriality. With Helmick back in the U.S. and Japan occupying Shanghai, Bertrand E. Johnson, a former Oklahoma judge on active duty in the war was summoned to preside over Carney’s case. Johnson convicted Carney of manslaughter and sentenced him to two years in prison. Under pressure from General Chennault and the Senate, though, President Roosevelt pardoned Carney. By then, the treaty had been ratified, extraterritoriality was ended, and the court was dismantled.

“I think by the end [Helmick] was very chagrined at how anomalous the court was, all things considered,” says Scully.

To this day, the U.S. Court for China remains something of a mystery. The National Archives and Records Administration holds some of its files, but most of the records produced by the court were handed to neutral Swiss authorities to protect after Pearl Harbor. Once the war was over, a U.S. consul recovered the records, only to leave a safe containing them under the care of the British Foreign Service in 1950, when Communists seized the Americans’ consulate. When the U.S. tried to recover the records two years later, the U.K. said its diplomats–unwilling to take responsibility for opening the safe the files were stored in–had left them behind.

It’s possible that the last vestiges of U.S. colonialism in China remain somewhere in Shanghai, securely locked inside a safe that no one’s bothered to open for 65 years.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook