Why Women Pretended to Be Creepy Rocks and Trees in NYC Parks During WWI

Can you find the camouflaged women hiding in these photos?

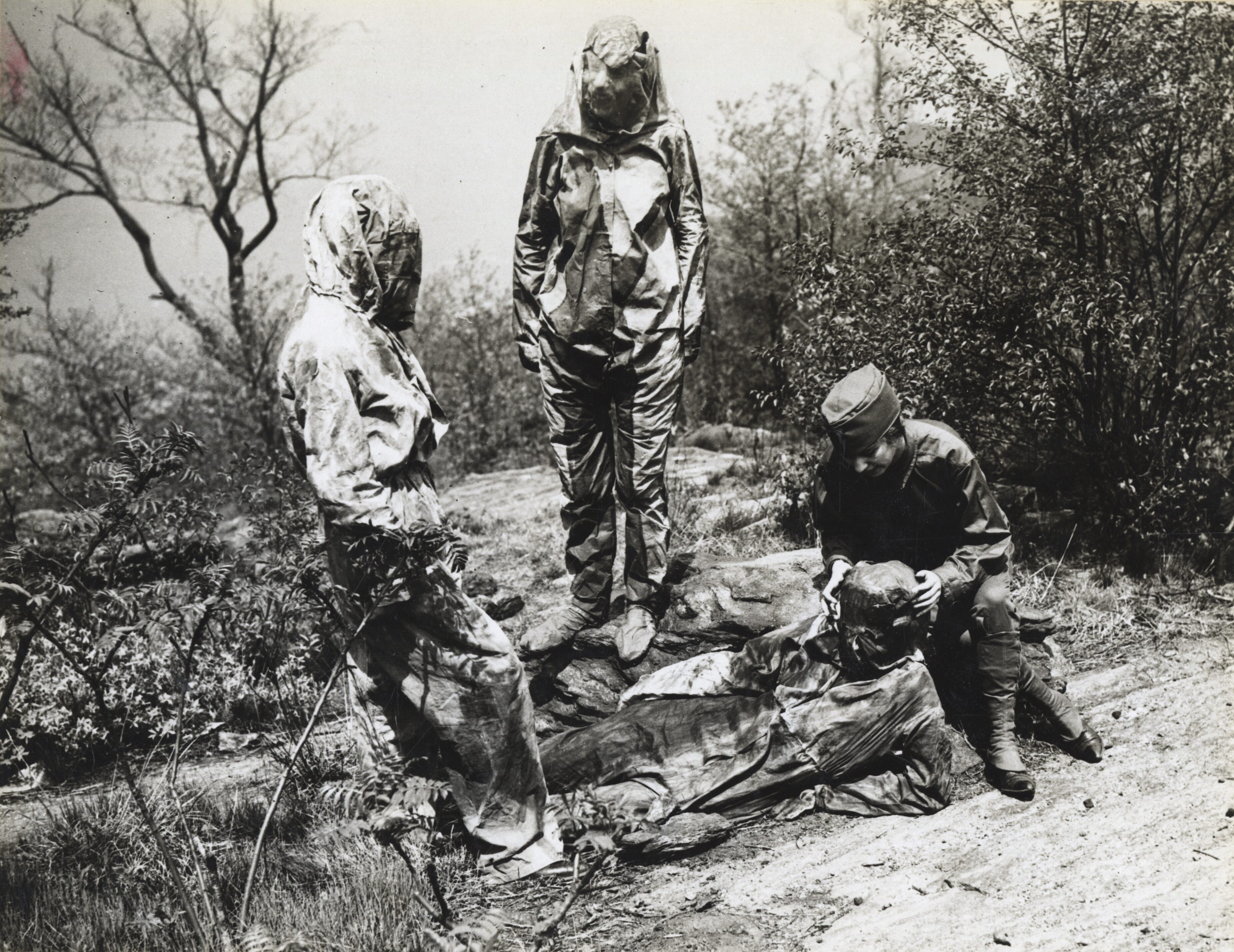

Three camoufleurs in the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps make one woman disappear into the forest floor. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-1)

Imagine taking a quiet stroll through the expansive wilderness of Van Cortlandt Park in Bronx, New York. You’re surrounded by a forest of oak trees, stony ridges, and a tranquil lake—completely isolated and alone in nature. But in 1918, visitors to the 1,146-acre park were unaware that they were in the company of a group of women hiding among the rocks, trees, and grass.

“Weird shapes, the color of the rocks and earth, moved here and there, and from the tops of trees came loud halloos and catcalls from other shapeless objects,” journalist Elene Foster wrote in the April 28, 1918 issue of the New York Tribune. “I stumbled over a hump of grass, which squealed when I stepped on it, and rose before me.”

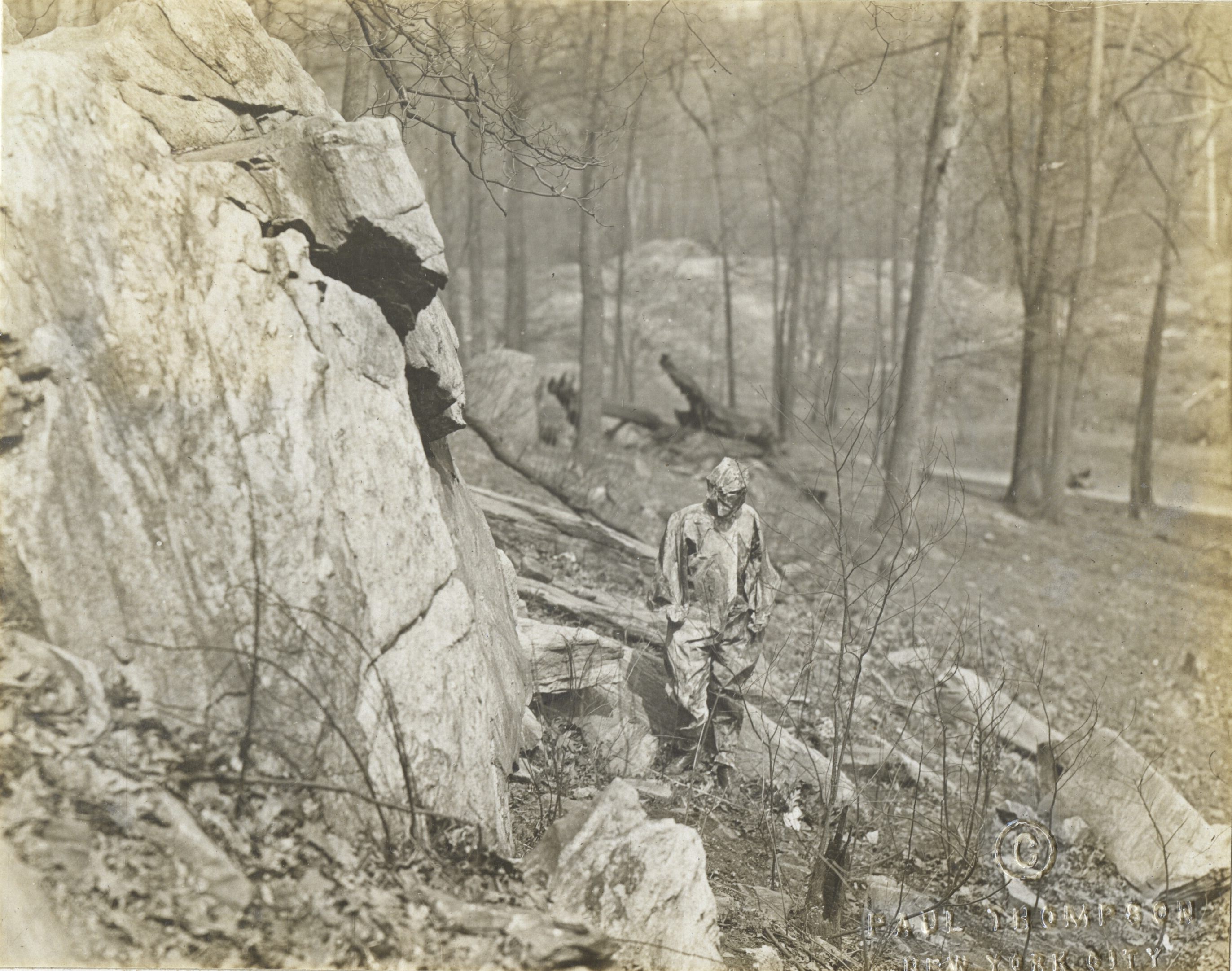

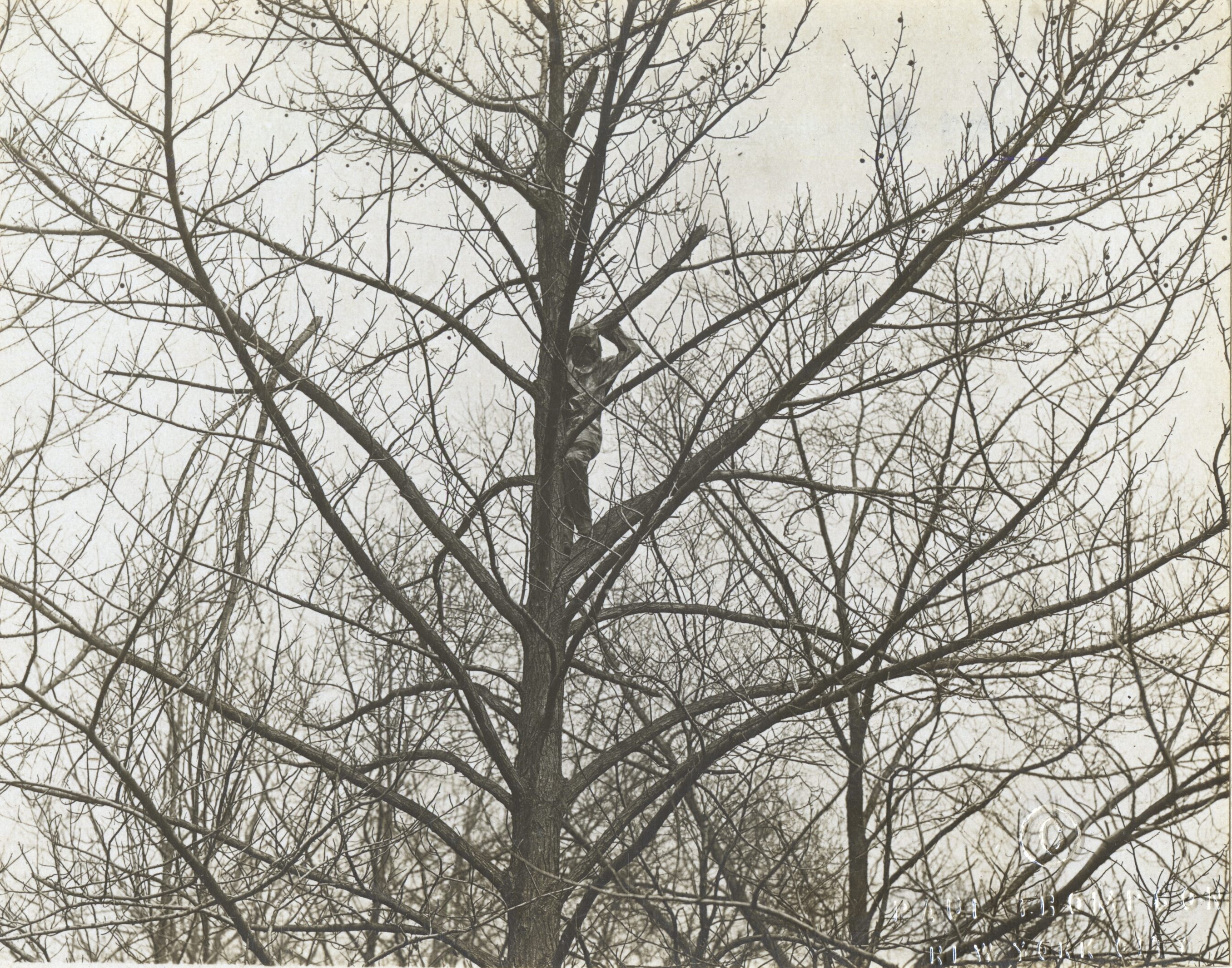

These hooded women were frequent park visitors. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-19)

The women disguised in special (and fairly creepy) dried grass or ”rock suits” were student military camouflage artists, or camoufleurs, of the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps, a forgotten division of the National League for Women’s Service.

Female artists across the United States joined the ranks of this highly specialized military group in New York to help with the war effort during World War I. They used their creativity and crafting skills to develop designs and patterns that mimicked the landscape to provide soldiers with added protection.

Parks were used as laboratories to test different camouflage suits, and city streets doubled as studios for them to paint dazzling, distracting designs on battleships.

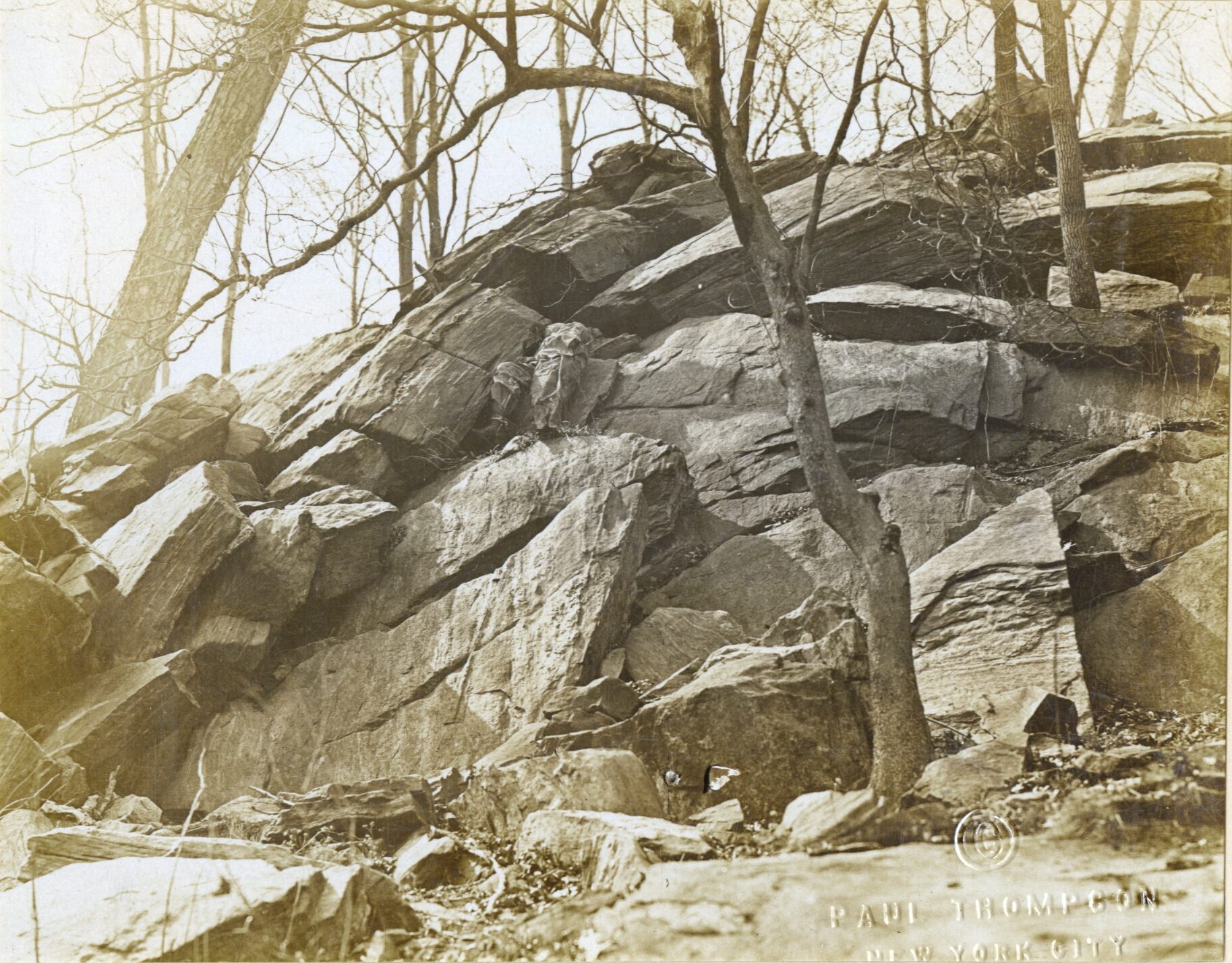

Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps sketch the landscape as a basis for their camouflage work at Van Cortlandt Park. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-23)

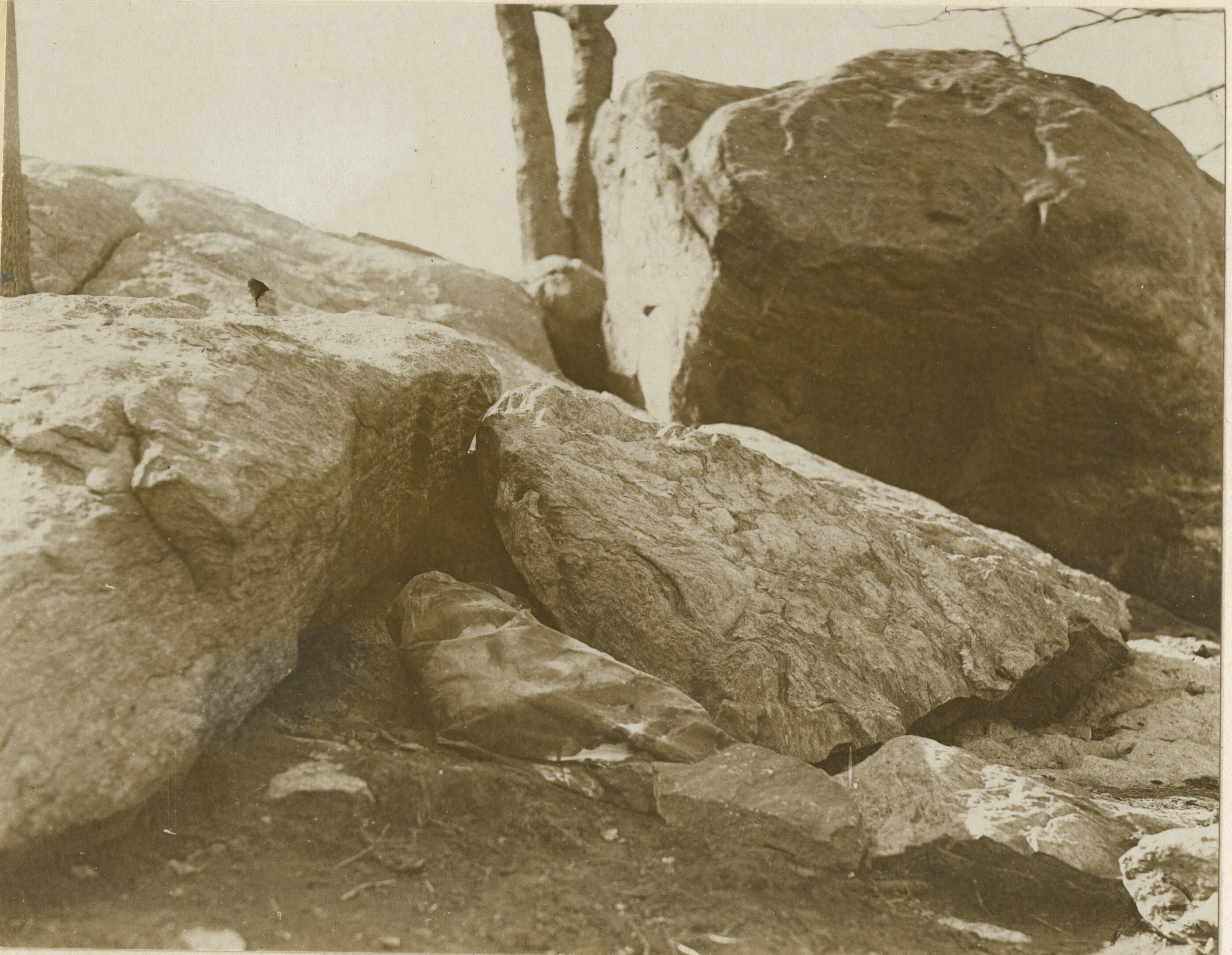

The photos uncovered by the National Archives and Records Administration reveal how the women hunched behind tree trunks or huddled against boulders, suddenly disappearing from view.

“The photos are really some of the most unusual I’ve come across during my time here,” says Richard Green, an archivist who’s worked at the National Archives for five years.

He found the 42 peculiar photos of the women in Van Cortlandt Park while working on the archive’s World War I film and photo digitization project. “There would be a picture of the girl and she would just fall down and disappear.”

Now you see her. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-21)

Now you see her. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-21)

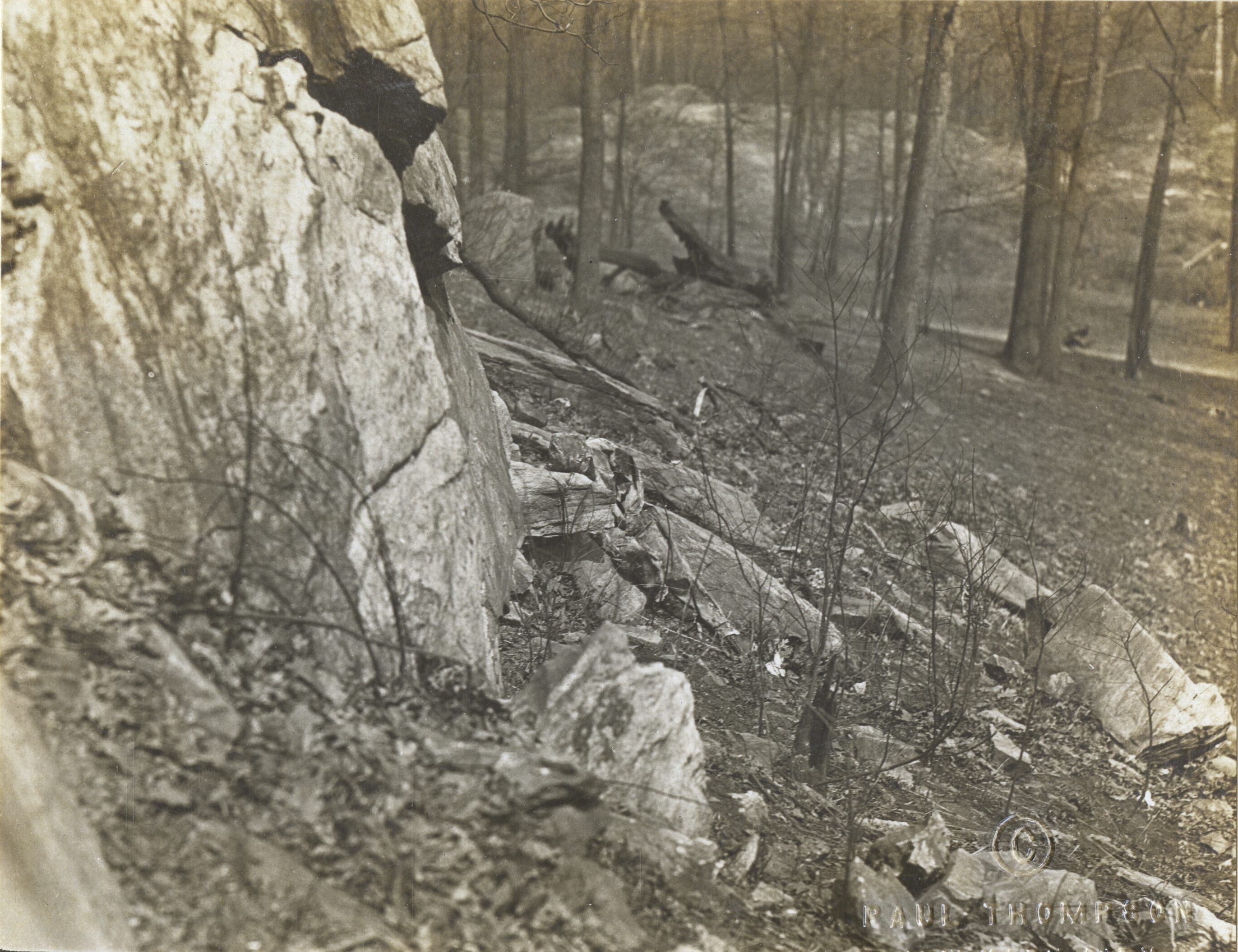

Now you don’t. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-29)

While the photos appear somewhat comical today, they tell of the historical significance of these female camoufleurs, Green says.

Women played a crucial role during the war effort, working in factories, hospitals, machine gun battalions, and many other military organizations. At the same time, camouflage became an increasingly important military tactic during World War I.

French painter and military telephonist Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola is said to be the first to suggest painting artillery earth-toned colors to conceal soldiers from the enemy. In November 1914, the French established a camouflage service and began developing different techniques, and recruiting artists, sculptors, architects, mold-makers, and cartoonists for the group.

It quickly evolved from decoys and dummies to a sophisticated art form of elaborately disguised rooftops and painted battleships.

Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps study camouflage at Van Cortland Part, New York. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-21)

As men had to leave camouflage units to fight at the front, the work was left to women. Following in the footsteps of England and France, the United States began training a group of 40 female artists on April 1, 1918 in New York, forming the first class of the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps.

The first group came from different parts of New York state and from Philadelphia, almost all of them working artists. To become part of the exclusive military unit, women had to have some training in painting, sculpture, photography, or wood carving, and be in perfect physical condition. All the women in the camouflage corps took the regular army physical examination. While there was no age limit, most women were in their early 30s, the oldest member of the first class being 45. After paying a $43 fee ($25 for the uniform, $18 for tuition), the women were ready to learn the art and science of camouflage.

“Camouflage is the sort of work which has a strong appeal to the woman with imagination who at the same time is clever at doing things with her hands,” wrote Foster.

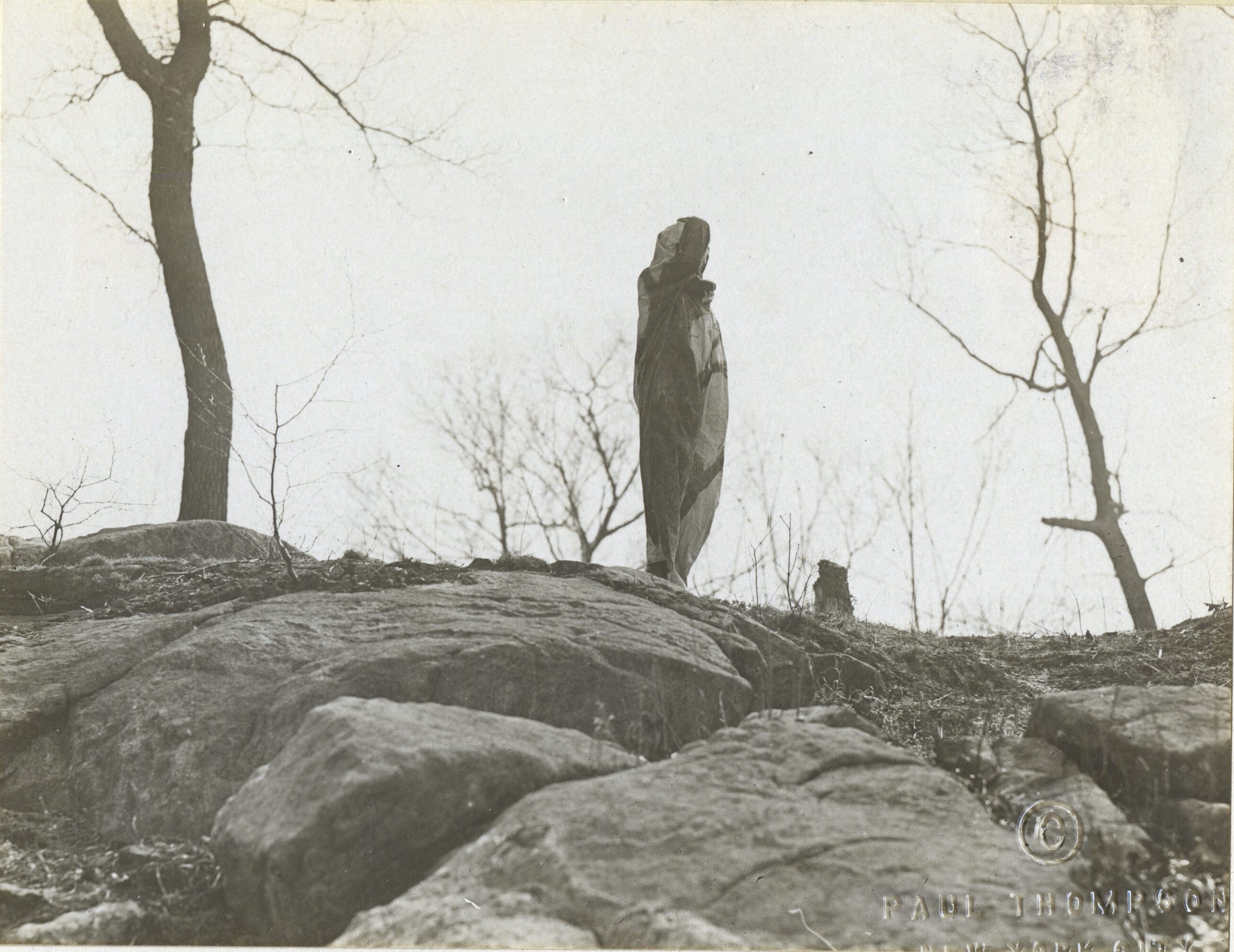

A camoufleur stands alone on the top of rocks. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-39)

The entire top floor of 257 Madison Avenue served as the main headquarters. Lieutenant H. Ledyard Towle of the 71st Infantry, who directed the division, conducted the same training he gave to the men of the New York Camouflage Corps. In order to create the best protection for soldiers, Towle firmly believed that the women should be taught the ins-and-outs of modern warfare, including army formations and maneuvers.

The intensive three-month course consisted of three indoor lectures and two open “field days” per week, where the women would survey the environment and test their designs. The successful camouflage techniques would be sent to the U.S. military.

Climbing up trees and holding fake branches. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-30)

Camoufleurs would don “rock suits” which could keep the wearer safe from detection at a distance of 10 feet, Green wrote in a blog post about the photos. “Observation suits” were colored so the person could blend into the sky, snow, or ice.

Park police were aware that the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps were experimenting in Van Cortlandt Park, but some admitted that they often couldn’t spot them. A policeman informed Foster that he knew they were among the rocks, “but ye can’t see thim till they move.”

A Living Rock. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-13)

They also had to learned how to disguise rail lines, depots, aircraft hangars, supply bases, and trenches. A British zoologist noticed that gray ships were easily spotted, and suggested painting abstract, multicolored patterns to confuse the enemy. So the group mastered a unique form of camouflage for battleships called “dazzle camouflage.”

The United States Navy started using dazzle camouflage in March 1918, painting 1,250 ships with odd patterns. Out of the 96 ships sunk by German U-boats after March 1918, only 18 of them were camouflaged, Green wrote.

Women apply dazzle camouflage to a ship in Union Square, New York City. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-9)

A dazzled battleship in the middle of Union Square. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-8)

All 42 photos of the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps are still in the process of being added to the National Archive catalog, but Green says that they will be made available for everyone’s enjoyment soon. While the women may have spent quite a bit of their time hiding in the forest cloaked in hooded suits, they wanted their work to be taken seriously.

“Please don’t go away with the idea that all we do is make costumes and dress up in them,” the camoufleur dressed as a patch of grass told Foster. “We are going to do every sort of camouflage work that they will allow us to do, from painting a battleship to making a fake tree.”

Try to see if you can find the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps artists in these photos:

Blending seamlessly with the boulders. (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-22)

Can you find the camoufleur? (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-18)

Can you find the camoufleur? (Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-18)

(Photo: NARA/165-WW-599G-21)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook