Goldfields Water Supply Scheme

An engineering masterpiece, or “Scheme of Madness?”

During the 1890s, much of the world was struggling economically. Many European countries were just starting to emerge from the “Long Depression” while in the U.S. the “Panic of 1893” had hit the economy hard. In Australia, banks were closing while unemployment soared. But on the Australian west coast, there was a ray of hope: Gold was discovered in Coolgardie, and men flocked to make their fortune on the diggings.

Thus begins the story of an amazing pipeline built to supply water to these Goldfields. Consisting of a source dam, a 310-mile pipeline and eight pumping stations, it was a massive engineering undertaking that, at the time, cost more than the annual budget of the State of Western Australia.

The trip from Perth, the capital city on the west coast, to Coolgardie, more than 500 kilometers (310 miles) to the east, was long and hard. Men (and a few women) walked, pushed barrows, cycled, or traveled by horse or camel through tough, desert country to seek their fortune. Temperatures were hot and the rivers and streams along the way were dry for much of the year.

There were some shallow wells, located about a day’s walk from each other along the route, known as Hunt’s Wells. But while adequate for a small number of explorers, after the discovery of gold in 1892, the wells couldn’t handle the number of travelers seeking gold. What’s more, a new railway line opened that sucked up much of the well water to power the stream trains.

This left no spare water for the gold miners at the Eastern Goldfields in Coolgardie. Entrepreneurs set up condensers to convert salt water from lakes and bores into fresh water, and “dryblowing,” a method to separate gold from the sand without using water, was invented. Bullock carts and then the railway transported water from near Perth to the goldfields, but the cost was exorbitant. The price of a bottle of water was reported to be higher than that of a bottle of whiskey.

Then in 1896, the Premier of Western Australia put forward the idea of a pipeline to transport water from near Perth to the Western Australia Goldfields, and convinced Parliament to take out a loan of £2.5 million to fund a water supply project — at the time, this amount was equal to the annual budget for the colony.

Engineer Charles Yelverton “CY” O’Connor was tasked with designing the pipeline. Water needed to be pumped more than 500 km and raised to an effective “head” of 824 meters. Nothing like this had ever been done before anywhere in the world.

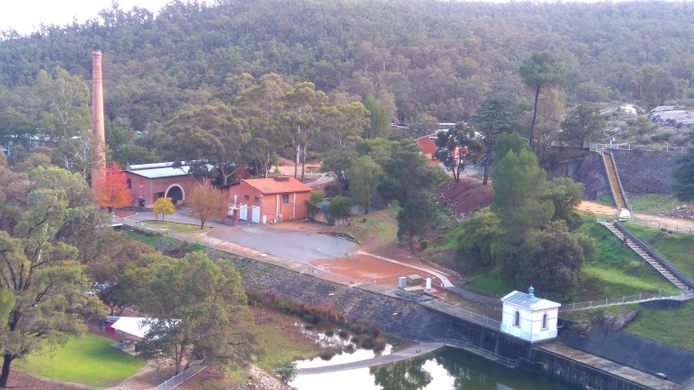

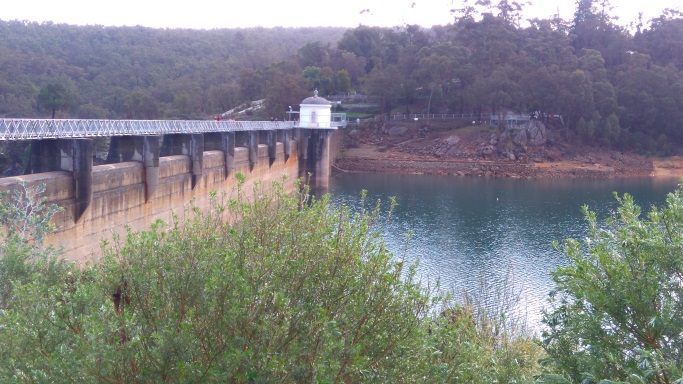

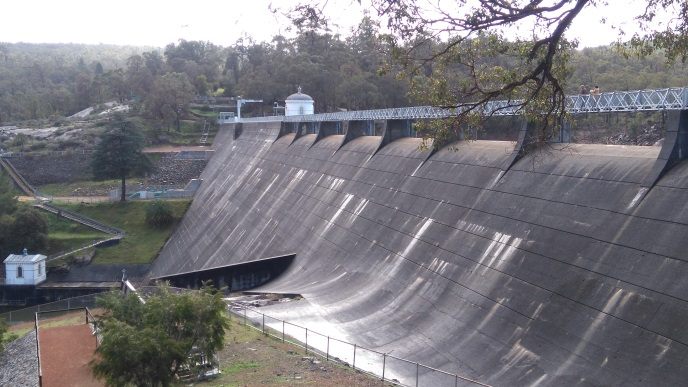

CY O’Connor decided to divide the pipeline into eight sections. It would start at a dam on the Helena River, Mundaring Weir, and would take 530 km (330 miles) of pipe carrying water to eight pumping stations. Construction of the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme began in 1898, and would take five years to complete.

Over the course of construction, O’Connor faced extreme criticism, including personal attacks, from politicians and press claiming the project was too ambitious and would be impossible to pull off. Critics called the pipeline the “Scheme of Madness.”

The extraordinary requirements that arose while constructing the pipeline resulted in a series of innovations. To avoid having to rivet the pipes, locking bars were developed that were made of lighter steel and offered less resistance to the water flow than rivets. Revolutionary caulking machines and ways to control leaks were developed.

But sadly, O’Connor never saw his masterpiece finished, as he took his own life in 1902, a year before its completion. Some blame a newspaper campaign accusing him and his colleagues of corruption and extravagance in the construction of the pipeline, though an official inquiry found no basis for the accusations.

The pipeline has since been extended to supply water to the areas north and south of the original line. About half the original pipes have been replaced, mainly with concrete-lined pipes, and the pumping stations evolved from coal-fired to wood-fired and then electric.

Today you can take a 2-4 day drive following the pipeline on what’s been dubbed the Golden Pipeline Heritage Trail. Maps are available to guide you to signposted stops where you can learn about the building and operation of the pipeline, including all eight pumping station sites, two of which have been converted to excellent museums. You can also learn about the early travelers walking from well to well, the building and maintenance of the railway, and significant events which have occurred in the region.

The Goldfields pipeline still supplies water to over 100,000 people in over 33,000 households, as well as mines, farms and other industries. It is a fitting memorial to one of the greatest engineers of his time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook