Wendover Air Force Base

The air force base that served as the secret training grounds for a B-29 bomber with a mission that would change the world

Enola Gay is a name that will forever bring a somber resonance.

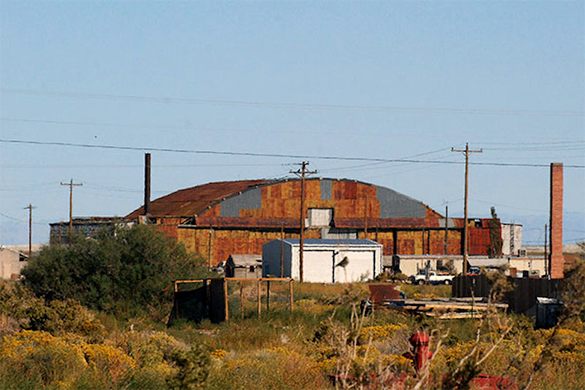

(via wikipedia) “Wendover Air Force Base is a former United States Air Forcebase in Utah now known as Wendover Airport. During World War II it was a training base for B-17 and B-24 bomber crews. It was the training site of the 509th Composite Group, the B-29 unit that dropped the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs. In 2009, a hangar at the base dubbed The Manhattan Project’s Enola Gay Hangar was listed as one of the most endangered historic sites in the U.S.[2]”

I’m in the Utah/Nevada border town of Wendover, 50 feet from the control tower of Wendover Field, where, in 1945, a B-29 bomber named after pilot Paul Tibbet’s mother Enola Gay departed on its way to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan.

Wendover was established in the 1920s by a fellow named Bill Smith, who built a gas station along the then-two-lane road. High atop a tall pole, he installed a single light bulb. Motorists approaching from the east across Bonneville Salt Flats could see the tiny beacon of light for miles.

Ever since I started taking road trips back in my college years, Wendover has been a welcome sight. It’s not much of a town — never has been — but for the last few decades it’s been a good place to escape the summer heat in a casino, gas up, or grab a hot turkey sandwich. Today, it’s growing like asparagus with a golf course, tract homes, and a half-dozen king-sized casinos. If you’re looking for a fancy hotel at a price cheaper than Motel Six, this is the place.

It’s sort of a strange feeling to be at Wendover Feld. In the summer of 1946, Colonel Paul Tibbets and his crew lifted off from here in a B-29 named the Enola Gay on their way to Tinian Island. From there, they went on to Hiroshima, Japan. At 8:15 a.m., August 6, bombadier Thomas Ferebee released an atomic bomb nicknamed “Little Boy,” destroying the city and marking the beginning of the end of World War II.

Tibbets and his crew trained in Wendover. So did a lot of other World War II bomber crews in their B-19s, B-24s

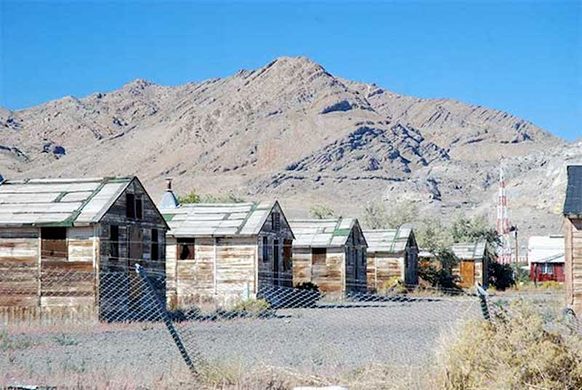

The barracks where World War II bomber crews stayed are still intact, but fading fast. and later in the king-sized B-29 Super Fortresses.

Early on, Tibbets didn’t know the specifics of his important mission. His crew never knew. In their first meeting, Tibbets told his men:

“You have been brought here to work on a very special mission. Those who stay long enough will be going overseas. You are here to take part in an effort which could end the war. Don’t ask what the job is. That’s a sure fire way to get transferred out. Do exactly what you are told, when you are told, and you will get along fine. . . .Never mention this base to anybody. This means your wives, girls, sisters, family.”

To make sure the crewman obeyed their leader, their phone calls were tapped and their mail censored.

Tibbets and his crew trained in Wendover for much of a year. In the surrounding desert, they dropped “orange pumpkins” shaped like A-bombs.

After four months of training, they flew to Cuba which they used as a base tofly overwater missions to practice targets near Bangor, Maine.

Wendover was chosen for the top secret mission (and for training other airman of the 8th Air Force) because it was so remote. By 1944, a total of 668 buildings were erected, and the base population was nearly 20,000. Twenty-one heavy bombardment groups were trained in Wendover. The 509th, Tibbet’s group, was formed December 14, 1944, and had as many as 1,700 members.

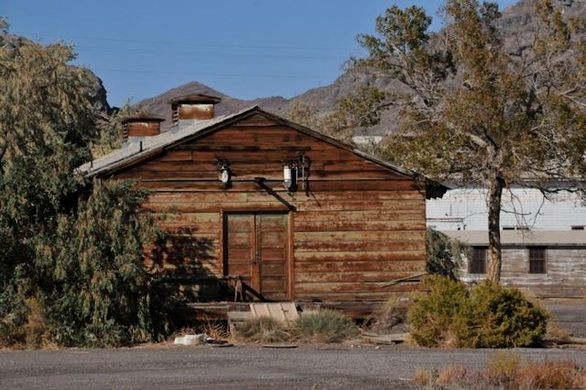

Today, you can visit Wendover Field, where many of the now-historic buildings are still intact, including the Enola Gay’s hanger. The plane, as I said, was named for Colonel Tibbet’s mother. I wonder how she felt about having her name attached to a plane associated with such a massive weapon of death.

The old Flight Operations Building contains scale models of the war years’ field, and is still in use for civil aviation.

If you want to explore the airfield, stop by the Visitor’s Center in Wendover, Nevada, for a free self-guided tour brochure. While you’re there, check out the display about the Enola Gay and the airfield, which is about a mile away across the border in Utah.

Wendover Air Force Base’s history began in 1940, when the United States Army began looking for additional bombing ranges. The area near the town of Wendover was well-suited to these needs; the land was virtually uninhabited, had generally excellent flying weather, and the nearest large city (Salt Lake City) was 100 miles (160 km) away (Wendover had around 100 citizens at the time).[3] Though isolated, the area was served by the Western Pacific Railroad, and many of its citizens were employed by the railroad.

Construction of the base and ranges began in September–November 1940.[4] The first military personnel arrived in August 1941. Facilities were Spartan, with a few barracks, officer quarters, and a mess hall. There were also some warehouses, a theater, a medical facility, and a few other buildings located on the airfield. By the end of 1941, Wendover airfield had been expanded with additional buildings and paved runways.

Wendover Air Base became a subpost of Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City on 29 July 1941. By that time a total of 1,822,000 acres (737,300 hectare) had been acquired for the base and associated gunnery/bombing range.[4] The gunnery range was 86 miles (138 km) long and 18–36 miles (29–58 km) wide. To provide water, a pipeline was run (1943) from a spring on Pilot Peak (Nevada) to the base.

Toward the end of 1943, Manhattan Project scientists at a secret mountain laboratory complex at Los Alamos, New Mexico, began to see the final form of their new creations. The bombs that could reduce whole cities to radioactive rubble were so large and complex that they would have to be delivered by special bombers and specially trained crews. So secret was the training operation that the crewmen themselves weren’t told exactly what they were training to do. It was run out of a tiny border town in northwest Utah.

Harvard physicist Norman F. Ramsey led the bomb delivery effort. (Ramsey would later share a Nobel Prize in physics for unrelated work.) “It was apparent,” he wrote later in a paper about the project, “that the only United States aircraft in which such a bomb could be conveniently internally carried was the B-29…. Except for the British Lancaster, all other aircraft would require such a bomb to be carried externally unless the aircraft were very drastically rebuilt.”

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress, which was first flown in September 1942, marked a quantum leap in bomber design. Because its fuselage was pressurized, crews could operate in shirt-sleeved comfort. A flight engineer tended the airplane’s systems, freeing the pilots to concentrate on flying. The big ships handled well, although the controls sometimes required a bit of muscle. But the B-29 was imperfect. In the labored climb to the stratosphere, the 2,200-horsepower Wright R-3350-13 Duplex Cyclone engines overheated dangerously. An engine fire, fed by the magnesium used to lighten the crankcase, could sever a wing.

Still undergoing tests at Eglin Field in Florida, the bomber would become operational in the summer of 1944.

In January of that year, on orders from General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, a B-29 from Smoky Hill Army Air Field in Kansas arrived at what is now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, to be secretly modified. Six thousand man-hours later, the airplane’s two 12-foot bomb bays had become a single bay 33 feet long, allowing the longer of the Los Alamos bomb designs to be tucked into the fuselage under the wing spar. The modified aircraft was to be the first of a very limited number of B-29s rigged for nuclear combat. The program was called Silver Plated, which was eventually shortened to Silverplate. There would be 65 Silverplate bombers in all.

In March 1944, the prototype Silverplate B-29 flew to California’s Muroc Army Air Field (now Edwards Air Force Base) to begin drop tests of full-scale dummies of the first two Los Alamos nuclear devices: the 17-foot-long Thin Man and the 10-foot-long, five-foot-diameter Fat Man. During these tests, a Thin Man replica escaped from its shackles before the bomb bay doors were opened, severely damaging the aircraft. “With this accident,” Ramsey wrote, “the first Muroc tests were brought to an abrupt and spectacular end.”

While the B-29 was repaired and the accident investigated, a team led by Navy Captain William S. “Deak” Parsons, inventor of the proximity fuse, worked on the detonation devices and bomb design. When the plutonium acquired for Thin Man was found to contain impurities that could trigger a premature detonation, the bomb was reconfigured to use uranium-235 instead. The new design, called Little Boy, was more compact—not quite 10 feet long and about two feet in diameter—and weighed about five tons. The Los Alamos scientists thought the bombs could be ready for combat by August 1945.

The prototype airplane, meanwhile, was restored to its two-bomb-bay configuration and re-fitted with the shackle and release mechanisms the British used to hang 12,000-pounders in the Lancaster. In September 1944, the prototype flew to the Glenn L. Martin modification center in Omaha, Nebraska, to serve as a template for bringing 24 B-29s up to the Silverplate configuration, which was still evolving.

At about the same time, Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets Jr., 29, was chosen to command the tactical unit created to deliver the special bombs. A B-17 commander with combat experience over North Africa and Europe, Tibbets had spent a year as a B-29 test pilot and knew the big, temperamental bomber inside and out. He believed that, once over Japan, the airplane’s performance would be more important than its protection. So he stripped his bombers of their state-of-the-art fire-control system, and of all guns and armor except those in the tail. The change pared more than 7,000 pounds from the aircraft, adding several thousand feet of operational altitude and improving maneuverability. At 34,000 feet, these stripped-down B-29s could out-turn a P-47.

Even as the Silverplates gave up their guns, the first standard B-29s touched down on Saipan, an island in the Northern Marianas that U.S. forces had taken in June 1944. Seabees (the Navy’s Construction Battalions, or CBs) were soon turning Tinian, Saipan’s southern neighbor, into a vast complex of airfields. North Field, with four 8,000-foot runways, would eventually be the world’s biggest airport, with hundreds of B-29s leaving to strike Japan.

The first military contingent arrived on 12 August 1941, to construct targets on the gunnery range.[4]

World War II[edit]With the entrance of the United States into World War II, Wendover Field took on greater importance. For much of the war the Wendover AAF and the Alamogordo AAF (in NM) provided the Army Air Force’s largest bombing and gunnery ranges.

In March 1942 the Army Air Force activated Wendover Army Air Field and also assigned the research and development of guided missiles, pilotless aircraft, and remotely controlled bombs to the site. The new base was supplied and serviced by the Ogden Air Depot at Hill Field.

Control Tower at Wendover

Abandoned World War II housing units at Wendover Army Air FieldIn April 1942, the Wendover Sub-Depot was activated and assumed technical and administrative control of the field, under the Ogden Air Depot. The Wendover Sub-Depot was tasked to requisition, store, and issue all Army Air Forces property for organizations stationed at Wendover Field for training.

By late 1943 there were some 2,000 civilian employees and 17,500 military personnel at Wendover. Construction at the base continued for most of the war, including three 8,100’ paved runways, taxiways, a 300,000-square-foot (28,000 m2) ramp, and seven hangars. By May 1945 the base consisted of 668 buildings, including a 300-bed hospital, gymnasium, swimming pool, library, chapel, cafeteria, bowling alley, two movie theatres, and 361 housing units for married officers and civilians.

South of the main airbase and runways, a facility was built for development of the technology necessary to drop the first atomic weapons. These buildings were known as the “Technical Site”, and were located as far as possible from the rest of the base for security and also for safety in the event of an accident. Today they are abandoned but still standing.

Heavy Bombardment Group training[edit]Wendover’s mission was to train heavy bomb groups. The training of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator groups began in April 1942, with the arrival of the 306th Bomb Group flying B-17s.

From March 1942 through April 1944 Wendover AAF hosted twenty newly formed B-17 and B-24 groups during one phase of their group training. In March 1942, heavy bomber training was a two-phase program, with each phase being six weeks. Later, the training was changed to a three-phase program, and each stage lasted four weeks. Wendover would do the second-phase training.

At Wendover, these groups utilized the huge Wendover Bombing and Gunnery Range southeast of the airfield.

Postwar use[edit]The training of B-29 aircrews and the testing of prototype atom bombs was the last major contribution of Wendover Field during World War II. After war’s end, some crew training continued, but at a reduced level. For a while, B-29s which had returned from the Marianas were flown to Wendover for storage. In the summer of 1946 the Ogden Air Technical Service Command assumed jurisdiction over all operations at Wendover Field except engineering and technical projects.

Wendover played a key role in the postwar weapons development industry. Three areas were being developed. The first were further testing of the JB-2 Loon flying bomb. The B-17 Flying Fortress, obsolete as a combat aircraft, was being tested to fly remotely. Gliding bombs, based on captured technology from the wartime Henschel Hs 293 German radio-controlled glide bomb were being developed that could be controlled by radar or radio. The third consisted of bombs that could be controlled by the launching plane. The historic GAPA (ground to air pilotless aircraft) Boeing project resulted in the first supersonic flight of an American Air Force vehicle on 6 August 1946. [6]

In March 1947, the Air Proving Ground Command research programs were moved to Alamogordo Army Airfield, New Mexico. as a result, 1,200 personnel from Wendover Field were moved to New Mexico from Utah and were relocated to Alamogordo to conduct guided missile research projects. Three ongoing projects were transferred: Ground-to-Air Pilotless Aircraft (GAPA), JB-2 Loon flight testing, and ASM-A-1 Tarzon gliding bomb.

Transferred to the Strategic Air Command (SAC) in 1947, Wendover was used by bombardment groups deploying on maneuvers. With the establishment of the U.S. Air Force as an independent service, the installation was renamed Wendover Air Force Base in 1947, inactivated in 1949 and retained in a caretaker status. It was transferred to the Ogden Air Material Area at Hill AFB in 1950 and the range continued to be used for bombing and gunnery practice.

Tactical Air Command (TAC) reactivated the base in 1954 and tactical units deployed there for exercises, utilizing the base for the next four years. TAC invested several million dollars renovating facilities. Wendover was transferred back to Ogden in 1958 and renamed Wendover Air Force Auxiliary Field, while the range was renamed Hill Air Force Range in 1960.

By 1965 the airfield was closed. The non-flying components were inactivated in 1969 and the entire facility was declared surplus in 1976.

In July 1975 the base was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1977 the federal government deeded much of the airfield to the City of Wendover, including the runways, taxiways, flight line, former hospital complex and hangars. Some acres, including the radar site, were retained by the military.

Beginning in 1980 the 4440th Tactical Fighter Training Group (Red Flag), Nellis AFB, Nevada, used Wendover for exercises, but they were discontinued after 1986.

Current uses[edit]Main article: Wendover AirportToday this former Air Force Base is used as a civil airport, with an unusually long runway for such a facility (there are two 8,000’ long runways). The facility was turned over to the town of Wendover as a municipal airport, named Decker Field.

Many of the buildings are leased for storage, and there is a daily charter flight (using Boeing 737 jetliners) into the airport carrying casino gambling charter passengers. A few General aviation aircraft are based at the field. Located at the west end of a corridor running between two restricted USAF gunnery ranges, the field is a convenient refueling and lunch stop for light planes traveling between Salt Lake City and Nevada or Northern California.

Wendover is one of the most intact World War II training airfields. It is also one of the most historic. The airfield is very isolated in northwest Utah, sitting in the middle of a vast wasteland miles away from any major population center. It is probably for this reason, and the dry hot climate, that much of the airfield remains today.

Still-extant facilities include the vast runway system, numerous ramps, taxiways, dispersal pads, and most of the original hangars (including the Enola Gay B-29 hangar). Most of the hospital complex and many barracks remain, as does a chow hall, chapel, swimming pool and many other World War II-era buildings. The control tower is still in use. A local group, “Historic Wendover Airfield”, is attempting to preserve the former base.

Numerous films and television shows have been filmed using Wendover Field.

One of these was the 1973 TV-movie Birds of Prey, in which stunt pilots flew and maneuvered helicopters inside one of the large hangars, possibly the first time this had been performed.

In addition to a post-war military base backdrop for the 1996 film Mulholland Falls, Wendover Field also stood in for the exteriors of Area 51 in the 1996 film Independence Day. Several flying scenes for the 1997 movie Con Air were filmed at Wendover, using Fairchild C-123K Providers, one of which was modified into a nonflying “prop” mounted on a bus chassis. Donated by the producers of the film, it now remains on the ramp as an attraction for visitors.

The northeast/southwest runway (3/21) has been pulverized and was used for base course material for the new 8/26 runway. The old east/west runway (7/25) was used by USAF engineers training for runway demolition and repair and is unusable. A joint program with the Utah National Guard will attempt to turn this into an assault training landing strip for C-130 and other aircraft. The mid-field east/west runway (8/26) is new, constructed in 1998 and is used as the main precision runway for the commercial Boeing 737 flights.

The base is also host to the Wendover Residency unit of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, as well as several exhibition spaces and workshops that resident artists and researchers use.

The Wendover airfield control tower is no longer in use. Visitors may ask permission to visit the now-empty tower cab for a panoramic view of the field.

The base is also used by Civil Air Patrol as the home of Desert Hawk Encampment.

The Atlas Obscura Podcast is Back!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook