After the Vietnam War, America Flew Planes Full of Babies Back to the U.S.

Operation Babylift had some problems, though.

The image is common enough: A passenger plane with human cargo belted snugly into their seats. But look for another second and you’ll see that every passenger is a child, and each one has been bundled up inside an identical cardboard box. Most of them are babies, but some are older and their limbs spill over the edges of their makeshift bassinets. They appear marooned without any adults in the shot.

The image is one of many taken during the chaotic end of the Vietnam War when the United States undertook an operation to evacuate thousands of children from Vietnam in April 1975, just weeks before the Fall of Saigon. Supposedly all orphaned, they were slated to be adopted out to waiting U.S. families. Over 2,500 children were brought stateside on flights manned by volunteers outnumbered by infants. Three processing centers were quickly formed at military outposts on the West Coast—two in California and one in Washington—where children were received before being placed with families throughout the country.

Doubts about some of the children’s orphanhood would bubble to the surface almost immediately, but before such questions could even be posed, those tasked with manning the operation had to grapple with an incredible logistical problem: quickly transporting and caring for thousands of infants during a time of pandemonium.

Bassinets crowd the seats of one of the PamAm flights. (Photo: National Archives/12007111)

Those who accompanied children on flights—including commercial flight attendants who were recruited or volunteered—used the materials on hand to turn planes into makeshift nurseries.

Flight attendant Jan Wollett told NPR that she and others lined the floor of their plane with blankets for the babies, and secured others with cargo netting.

One Pan Am flight attendant recalled stashing babies in cardboard bassinets both on and underneath seats. During the flight she dodged “midget bodies crawling in the aisles” and checked babies with a flashlight:

“We constantly peeked into bassinets to make sure each baby was still breathing. I froze as I flashed my light on each little back, waiting for what seemed like hours to see a ribcage move with the breath of life.”

A nurse and babies arriving into San Francisco as part of Operation Babylift. (Photo: National Archives/23869151)

A nurse who accompanied a planeload of children to Seattle wrote that she was “overwhelmed” as she saw “the endless flow of little ones pouring into the plane filling every available space.” She did not sleep during the 30-hour flight.

Jim Trullinger was doing doctoral research in Vietnam when forced to flee the country. He secured a trip back to the United States with Operation Babylift. “When we got to the airport, I helped carry babies onto the plane, a 747 charter, and strap them into their seats,” he wrote. “There were no baby carriers, so we just had to use seat belts tightened around the babies. There were so many babies that there was no place for me to sit. Before take-off, the flight attendant told me that if there was a crash, I was to get off the plane first and she would toss babies to me.”

Catastrophe was fresh in everyone’s minds, as the first scheduled flight of Operation Babylift flight had crash-landed on April 4th, killing many of the passengers, including 78 children.

Upon arriving in the United States, planes were met by medical teams that triaged groups of children who were suffering from a range of maladies such as severe dehydration, intestinal illnesses, pneumonia, skin infections and even chicken pox. Ambulances rushed the sickest to hospitals. Around half of the children flowed through San Francisco’s Presidio. Now a lush recreation area, the Presidio was an army base at the time and a cavernous football field-sized building called Harmon Hall was transformed into a massive care facility.

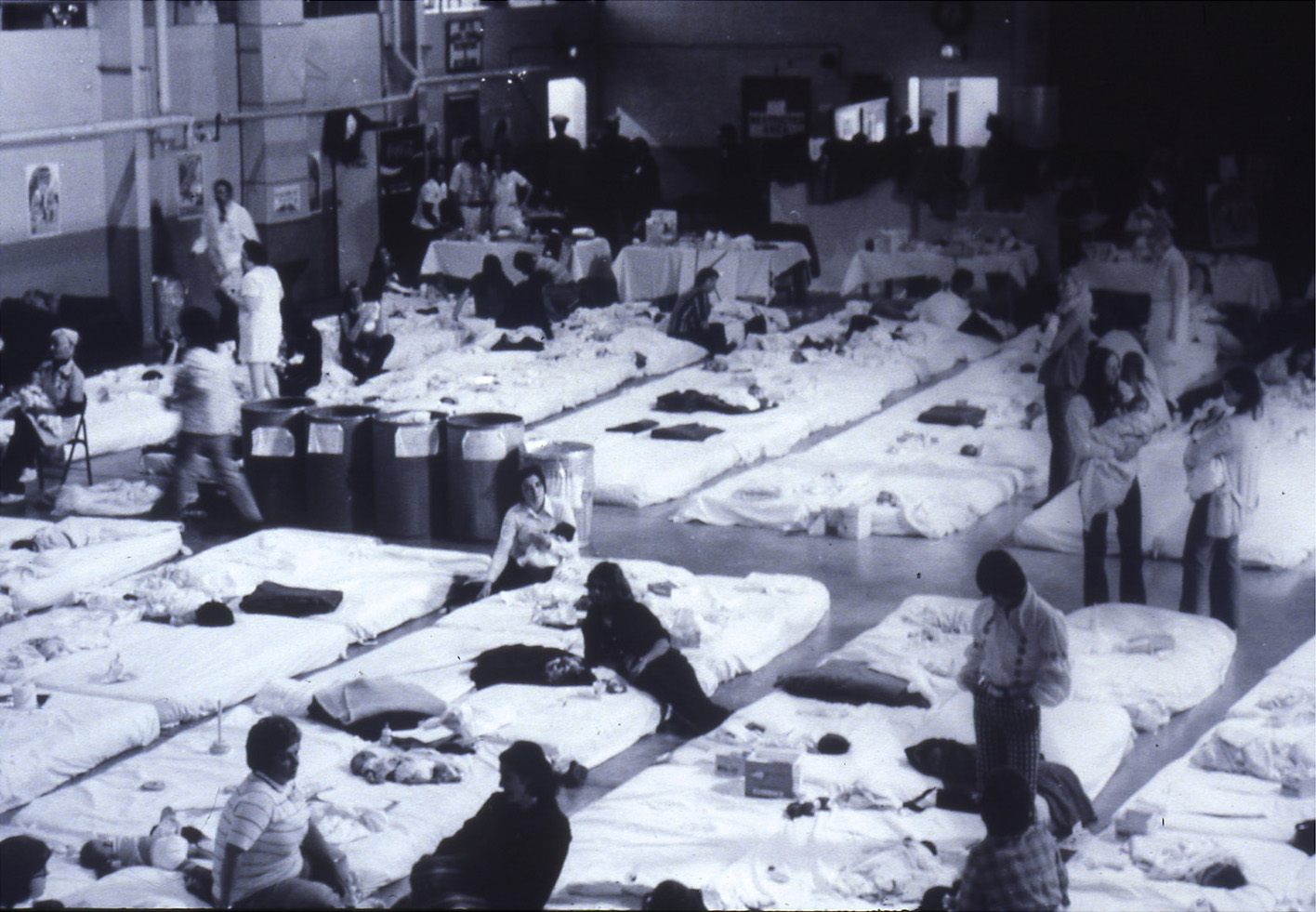

Harmon Hall was turned into a care facility for the babies. (Photo: Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives and Records Center)

Michael Howe was the president of the Bay Area Health Planning Council at the time, a voluntary organization that oversaw the direction of healthcare and hospitals in San Francisco. Organizers tapped him to help, and he became a volunteer coordinator at the Presidio, working with nursing students, Vietnam veterans and others to assist in caring for the children. In 2015, Howe revisited Harmon Hall with a group of fellow volunteers as well as men and women who had arrived as children on Operation Babylift flights. He described the setting as “extraordinary”.

“How did we do this?” he wondered, “Did we really do this?”

When the children started arriving, it was a chaotic scene. “There was really no one in charge and in some way it’s kind of a misnomer to call me or anybody else a leader—we were there doing what we possibly could do in an environment where we really weren’t quite sure what to do, bottom line,” says Howe.

The hall was lined with small mattresses for the babies; when mattresses ran short, children were sometimes placed on layers of blankets on the floor. Half of the facility was devoted to support services for the children; part to feeding volunteers who worked long shifts, sometimes sleeping at the facility. The children were sick, and volunteers fell sick as well. In very rare cases, people who felt they had been promised a child for adoption would show up at the Presidio and try to abscond with a baby.

An April 6, 1975 San Francisco Chronicle article reported that there were “7,886 bottles of formula, at least 10,000 disposable diapers, 2,400 cotton tipped swabs and 750 cotton balls, 1,440 aspirin tablets, gallons of baby powder, ointment by the bushel, toothpaste and towels” on hand at the Presidio. The same article described a plane bound for Seattle “crammed with bassinets, diapers, bottles, and food including hot dogs.”

President Ford carries a baby from one of the Operation Babylift planes. (Photo: National Archives/7839930)

As they marshaled the resources to care for thousands of children, volunteers—who were not involved in the decision to receive or adopt out children—quickly began to doubt whether every child was without family

“There are unquestionably children in the airlift who are true orphans,” Jane Barton, a translator from the American Friends Services Committee told the San Francisco Chronicle on April 13, 1975. “But I talked to a number of children who said they are not orphans.”

Howe, too, had concerns.

“I felt it before we closed out our work,” says Howe. “The word ‘felt’ is important—I had no proof.”

Did the U.S. save kids—or steal them? The legacy of Operation Babylift is a deeply complicated one. Lawsuits were filed on behalf of the children including one brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights in 1975 that sought to reunite adoptees with living relatives. Some have successfully formed relationships with biological family as adults while others are still searching. Many have made the pilgrimage back to Vietnam to reconnect with their roots, reversing the flights they took over 40 years ago, scattered in the cabin of an airplane filled with crying babies.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook