For Hundreds of Years, People Thought California Was an Island

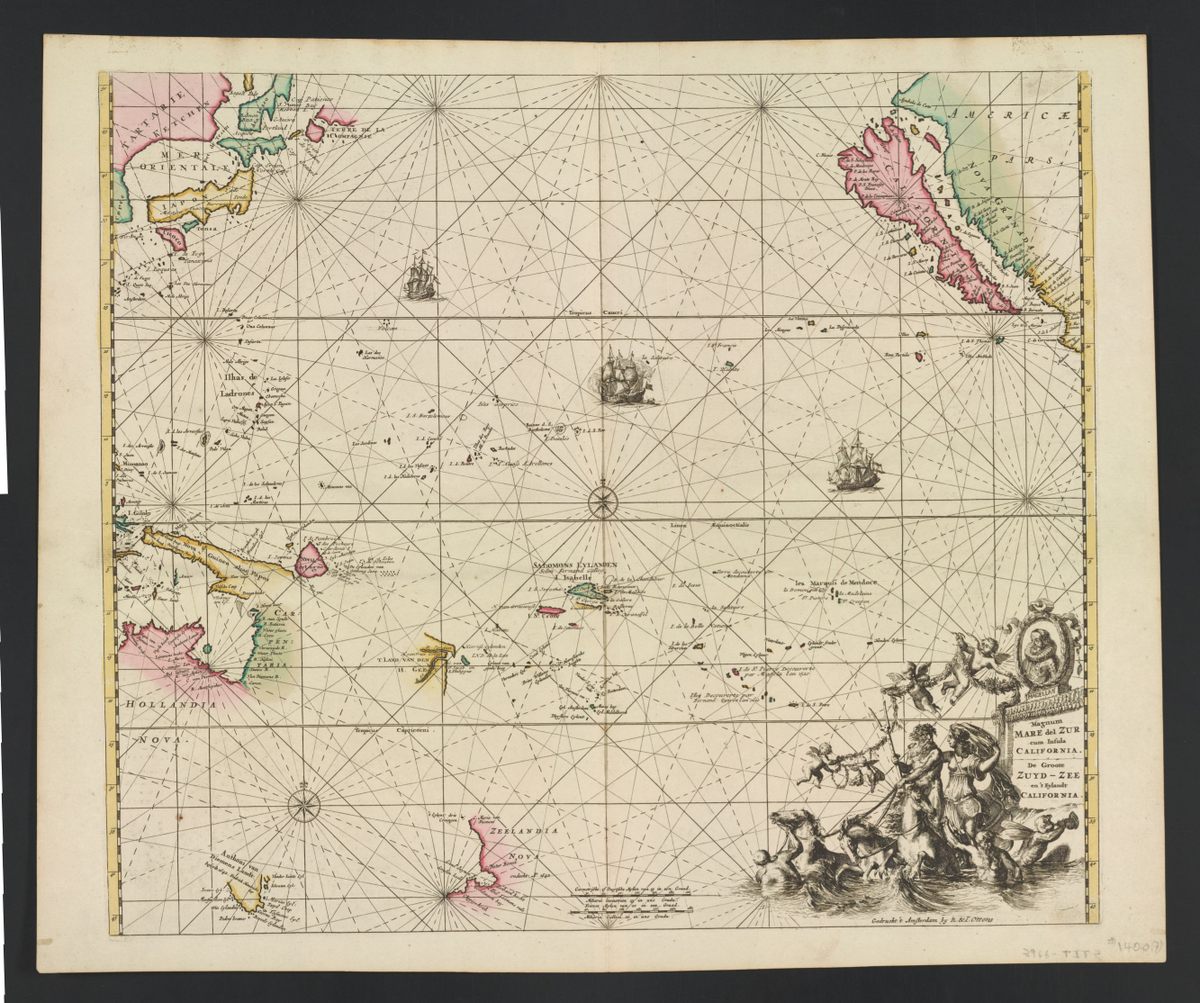

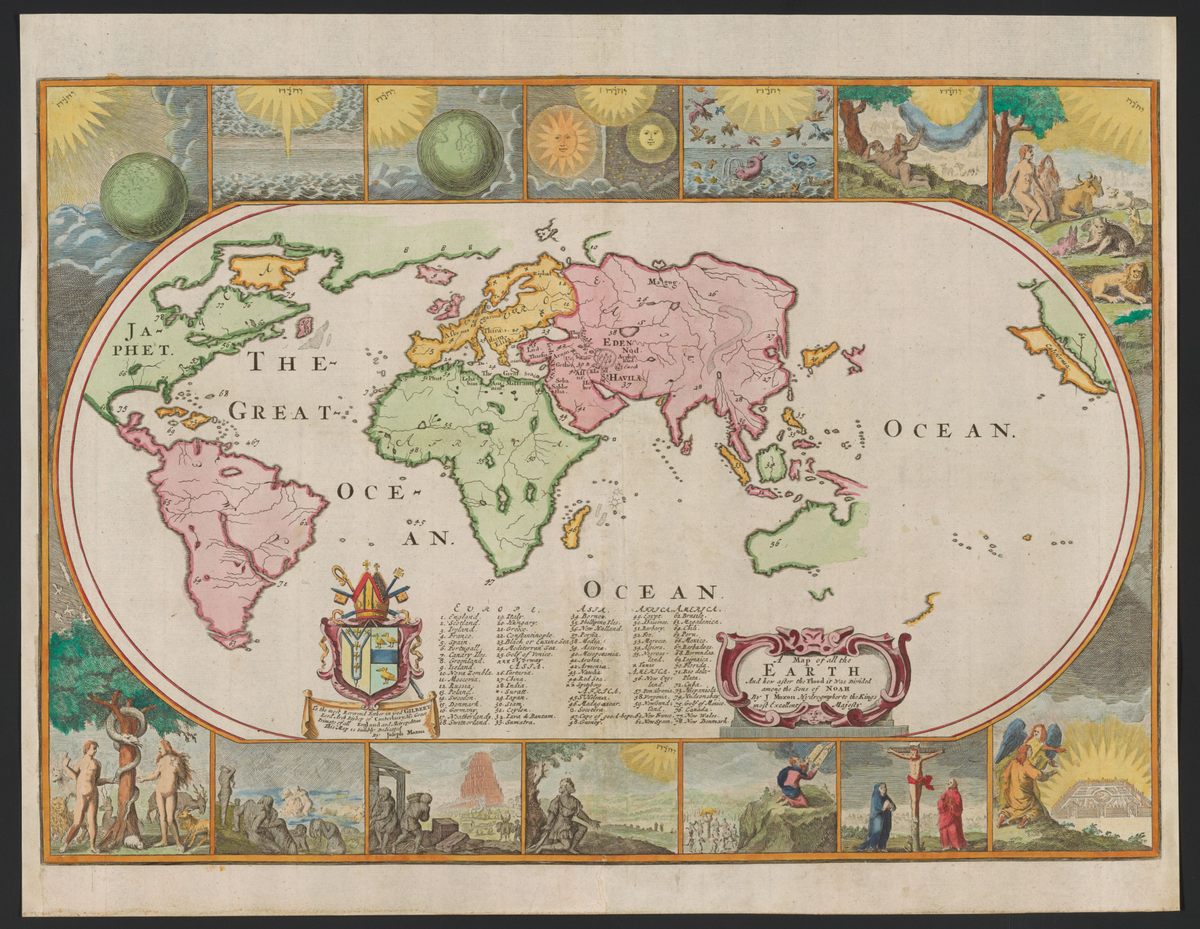

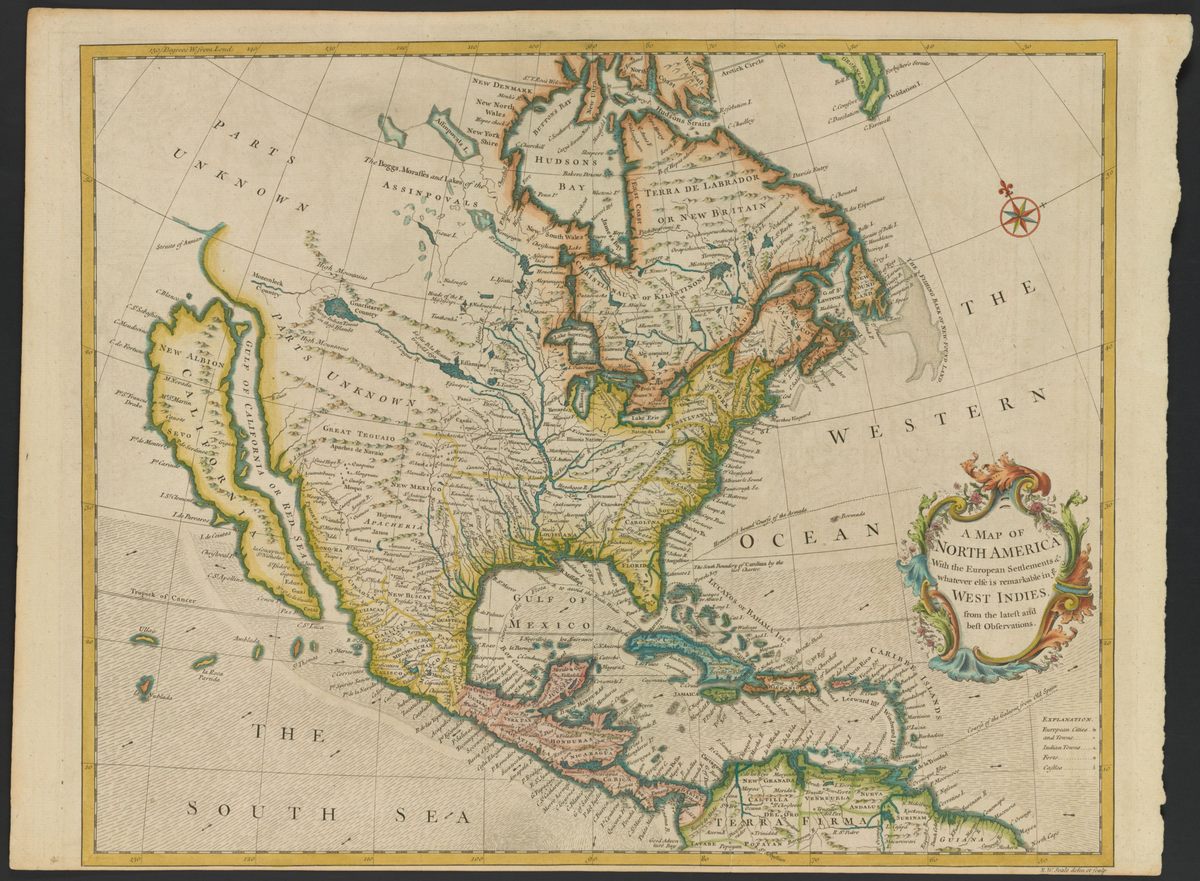

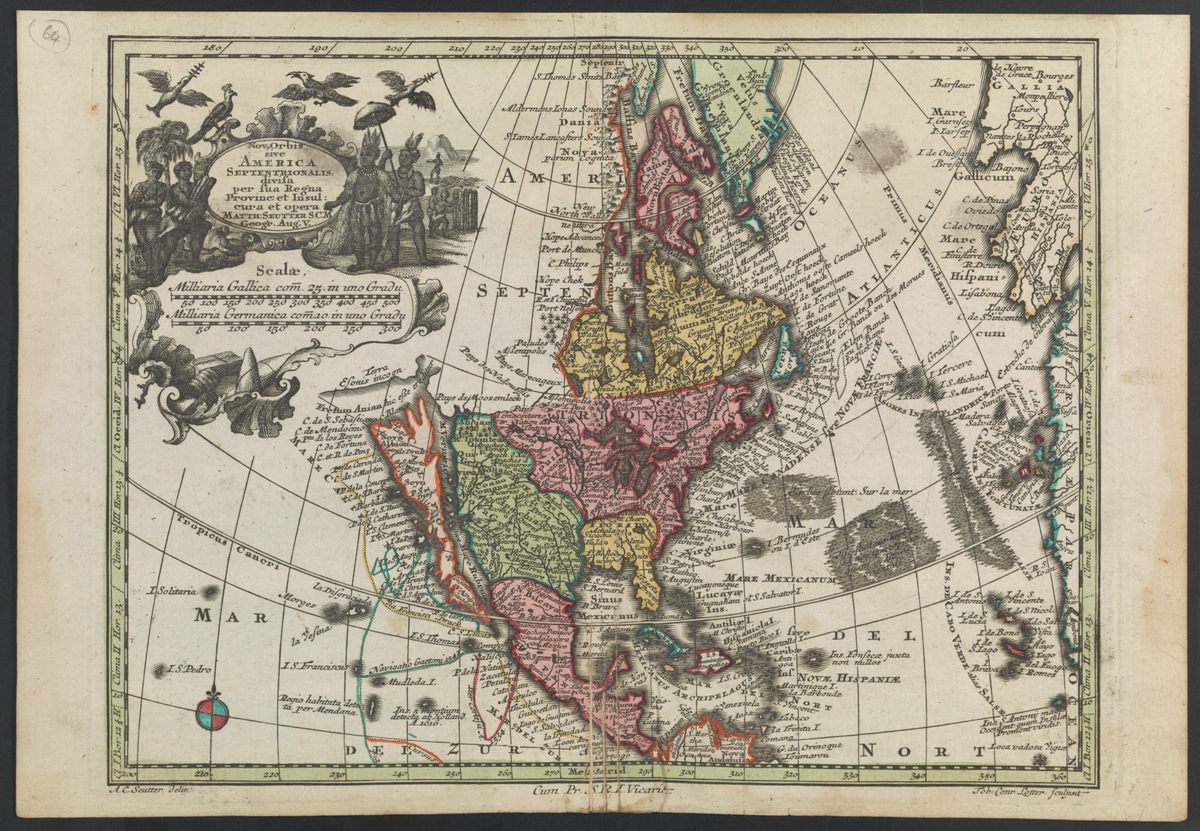

Dozens of maps show cartography’s most persistent mistake.

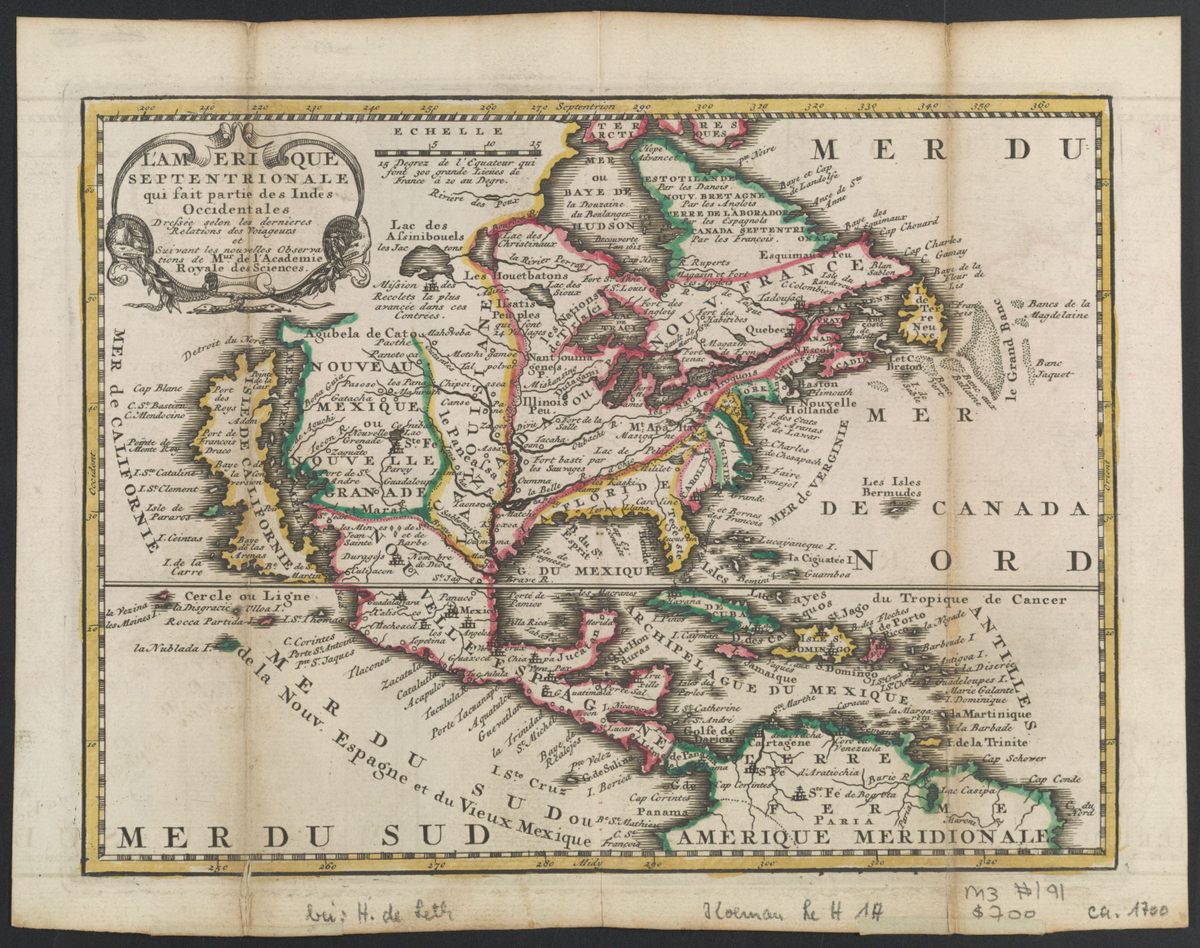

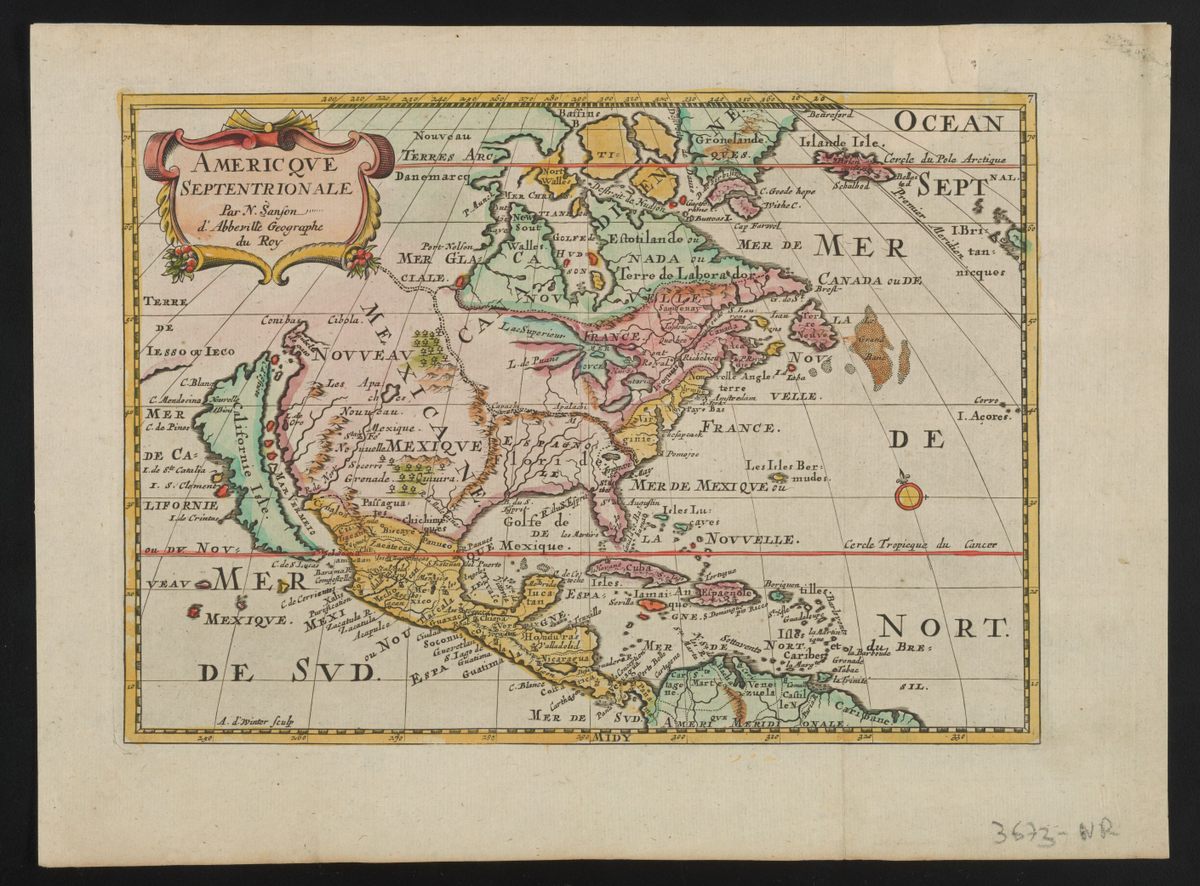

In 1971, Glen McLaughlin came across a strange map in a London map shop. Americæ Nova Descriptio, produced by Anne Seile (1) in 1663, showed California as a big, carrot-shaped island, floating off the coast of North America.

McLaughlin, a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley, bought the map and hung it on a wall at home. It turned into a popular talking point with visitors, and California-as-an-island became McLaughlin’s decades-long obsession.

Over the next 40 years, he collected more than 700 maps, charts, and other cartographic objects on the topic, building up a visual library of what is one of history’s most persistent cartographic fallacies.

First mention

Perhaps that persistence and McLaughlin’s obsession spring from the same source. Even though California geographically isn’t an island, it does tend to feel like a place separate from the “mainland.”

Indeed, in more ways than one, California is a one-off. Some metrics are obvious. It’s so vast and varied that it could easily be a country on its own, let alone an island. California is the largest state by population (40 million) and GDP ($3 trillion, 15% of the U.S. total). It’s home to both the highest and lowest points in the contiguous United States: Mount Whitney (14,505 feet; 4,421 meters) and Badwater Basin in Death Valley (-282 feet, -86 meters).

But the Golden State is special in a more intangible way as well. It’s where America’s westward expansion met its ultimate physical barrier: Manifest Destiny, say hi to Pacific Ocean. Both the 1849 Gold Rush and the birth of Hollywood, half a century later, merely confirmed the image of California in the popular mind as the final destination of the American Dream—there to flourish or wilt.

Amputation, CA

It’s fitting that a state so synonymous with storytelling should have started out as an invention itself. California is the only state that was named after a fictional place. Bound up with its name was the misconception that California was an island—and so it would remain on many maps, until as late as 1865.

In 1533, a mutineer from Hernan Cortez’ expedition into Mexico landed on a peninsula so elongated that he mistook it for an island. He named it after a fictional island in Las Sergas de Esplandian (‘The Deeds of Esplandian’), a romantic novel then popular in Spain. It says that:

“[O]n the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of the Amazons.”

The women were gorgeous, brave, and strong, and their weapons were all made of gold—the only metal available on the island.

American Caliphate

Though the name “California” can be traced to a specific novel, its etymology remains disputed. In the novel, the island is ruled by Queen Calafia. Her job title suggests a derivation from the Arabic caliph (“ruler”)—“California” would thus mean something like “Caliphate.”

Another theory pinpoints the name’s origin to “Califerne,” a place mentioned in verse CCIX of the medieval Song of Roland (and also deriving from “caliph”), while a third one posits a derivation from Kar-i-Farn, Persian for “Mountain of Paradise.” One more: calit fornay, Old Spanish meaning “hot furnace.”

As early as 1539, an expedition by Francisco de Ulloa demonstrated that the area (near the southern tip of present-day Baja California, Mexico) was a peninsula after all. But fiction proved stronger than fact. Even though the earliest maps do show California attached to the mainland, the name for the place stuck.

Spanish vs. English

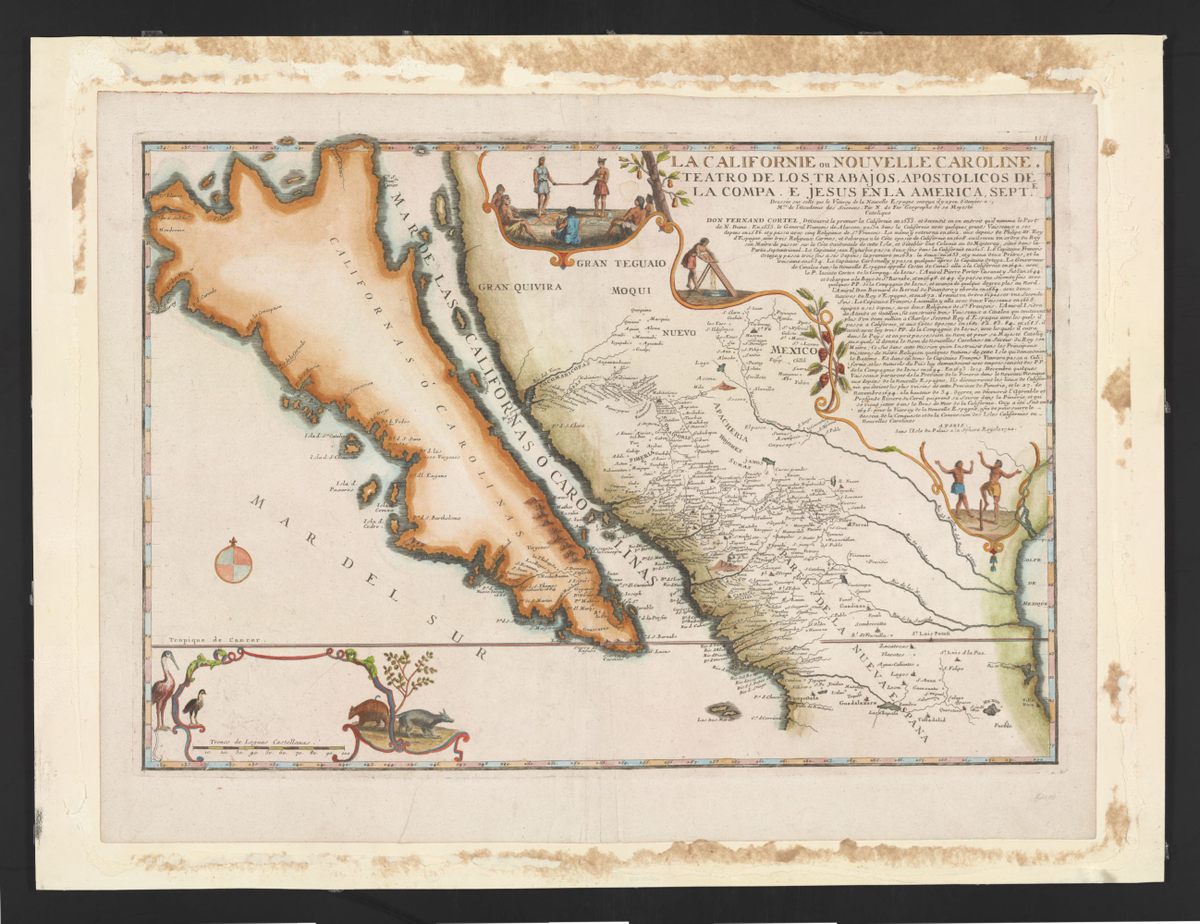

But the idea of the island of California proved pretty tenacious too. After an 80-year period of continental attachment, California started to appear on maps as an island, from 1622 onward and far into the 18th century.

California’s insular revival is generally ascribed to Antonio de la Ascension, a Spanish clergyman who had sailed along North America’s West Coast in the early 1600s and yet, contrary to the evidence, claimed California was an island.

Perhaps this was to invalidate the English claim on the continent. In 1579, Sir Francis Drake had landed at a place he called “Nova Albion” (today known to be Point Reyes, California), and claimed the region for England. If Drake’s landing could be situated on an island, De la Ascension seems to have thought, Spain’s claim to the mainland itself would remain undisputed.

Geography, “rectified”

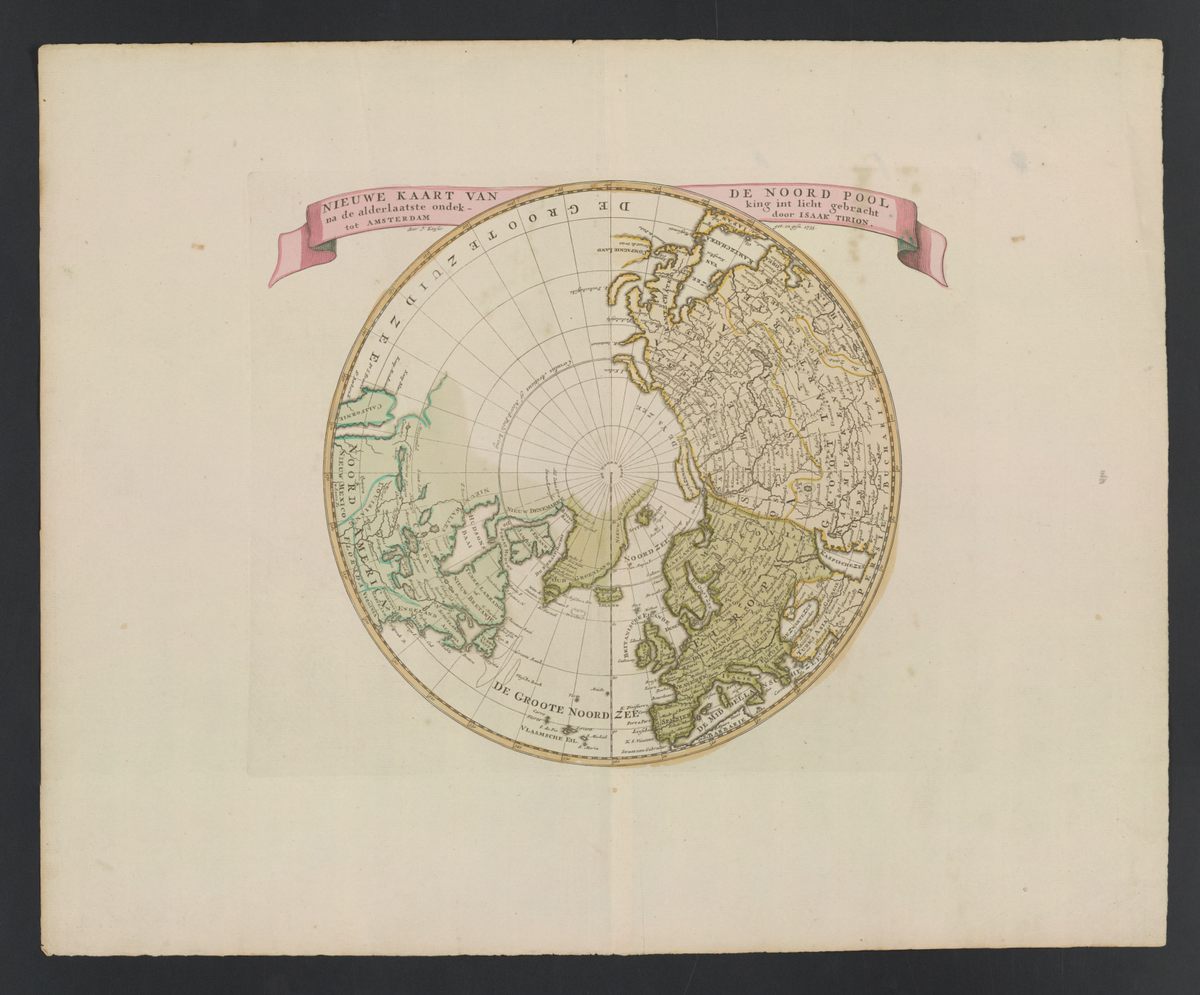

That it would take more than a century to set the record straight again speaks to California’s by now semi-legendary status. Other famous cartographic legends on the map of the Americas include Norumbega, El Dorado, and Siete Ciudades.

Father Eusebio Kino’s expedition (1698-1701) proved—again—that California was connected to the North American mainland. The title of his report left no doubt: “A passage by land to California”. Still, not everyone was prepared to give up the ghost of California Island.

However, by 1747, King Ferdinand VI of Spain had had enough. Tiring of the persistent falsehood infesting his maps, he simply decreed that “California is not an island.” Only after this was reconfirmed by the expeditions of Juan Bautista de Anza (1774–1776) was the fiction definitively laid to rest.

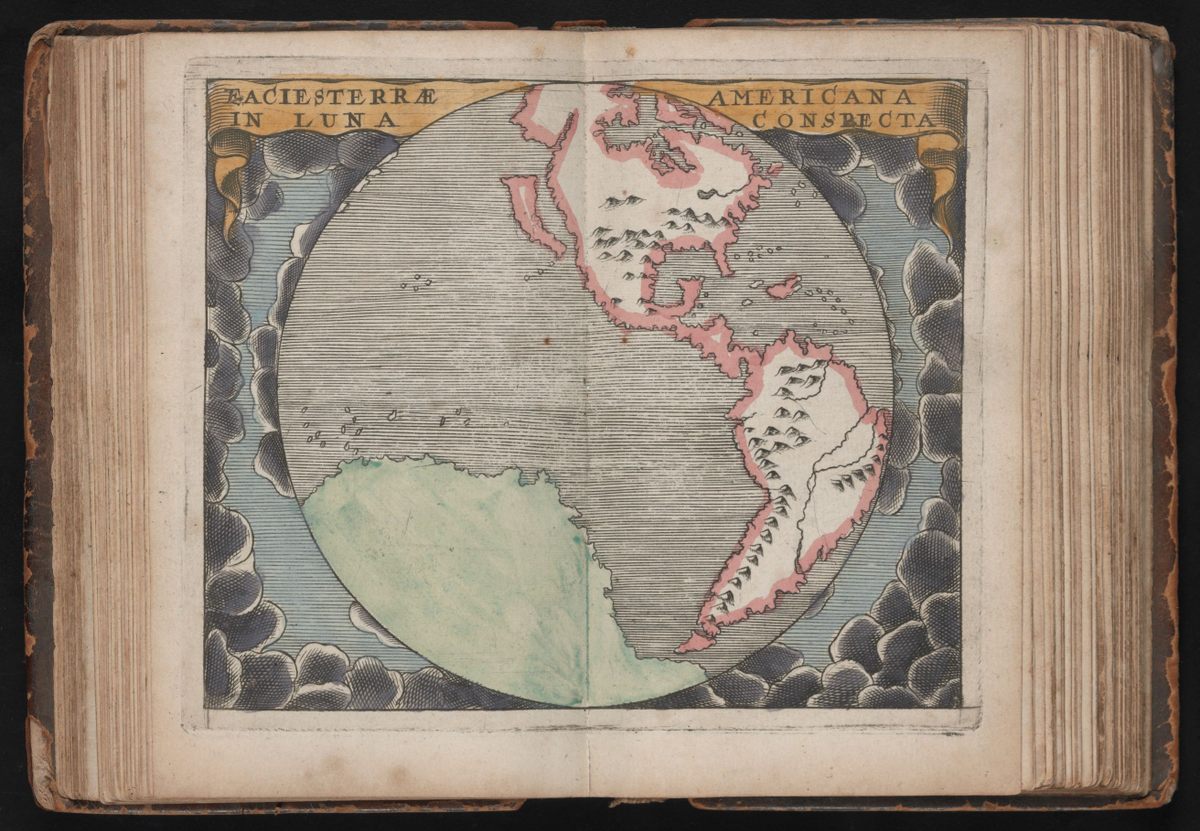

A lunar view

But it’s hard to kill a ghost, and cartographic specters are particularly persistent. Even as the rest of the world caught up with the facts on the ground, a Japanese map in 1865 showed California—by then thoroughly explored, well described, and increasingly populated—as an island nevertheless, the last such occurrence in cartographic history.

Glen McLaughlin’s collection is testament to the mesmerizing power of map mistakes, over other cartographers and over collectors like himself. In 2011, and by then in his 80s, he had had enough, though: He parted with his collection, which was acquired in its entirety by Stanford University. It’s now online in its entirety, featuring these maps and many others.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook