Everything You’ve Heard About Chastity Belts Is a Lie

Including their very existence.

What was the chastity belt? You can picture it; you’ve seen it in many movies and heard references to it across countless cultural forms. There’s even a Seattle band called Chastity Belt. In his 1969 book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), David R. Reuben describes it as an “armored bikini” with a “screen in front to allow urination and an inch of iron between the vagina and temptation.”

“The whole business was fastened with a large padlock,” he writes. With this device, medieval men going off to medieval wars could be assured that their medieval wives would not have sex with anyone else while they were far, far away, for years at a time. Yes, it sounds simultaneously ridiculous, barbarous, and extremely unhygienic, but … medieval men, you know? It was a different time.

This, at least, is the story that’s been told for hundreds of years. It’s simple, shocking, and, on some level, fun, in that it portrays past people as exceedingly backwards and us, by extension, as enlightened and just better. It’s also, mostly likely, very wrong.

“As a medievalist, one day I thought: I cannot stand this anymore,” says Albrecht Classen, a professor in the University of Arizona’s German Studies department. So he set out to reveal the true history of chastity belts. “It’s a concise enough research topic that I could cover everything that was ever written about it,” he says, “and in one swoop destroy this myth.”

Here is the truth: Chastity belts, made of metal and used to ensure female fidelity, never really existed.

When one considers the evidence for medieval chastity belts, as Classen did in his book The Medieval Chastity Belt: A Myth-Making Process, it becomes apparent pretty quickly that there’s not much of it. First of all, there aren’t actually all that many pictures or accounts of the use of chastity belts, and even fewer physical specimens. And the few book-length works on the topic rely heavily on each other, and all cite the same few examples.

“You have a bunch of literary representation, but very few historical references to a man trying to put a chastity belt on his wife,” says Classen. And any literary reference to a chastity belt is likely either allegorical or satirical.

References to chastity belts in European texts go back centuries, well into the first millennium A.D. But until the 1100s, those references are all couched in theology, as metaphors for the idea of fidelity and purity. For example: One Latin source admonishes the “honest virgin” to “hold the helmet of salvation on your front, the word of truth in the mouth … true love of God and your neighbor in the chest, the girdle of chastity in the body … .” Possibly virgins who took this advice went around wearing metal helmets and keeping some physical manifestation of the word “truth” in their cheeks, like a wad of tobacco, in additional to strapping on metal underwear. Or, possibly, none of this was meant to be taken literally.

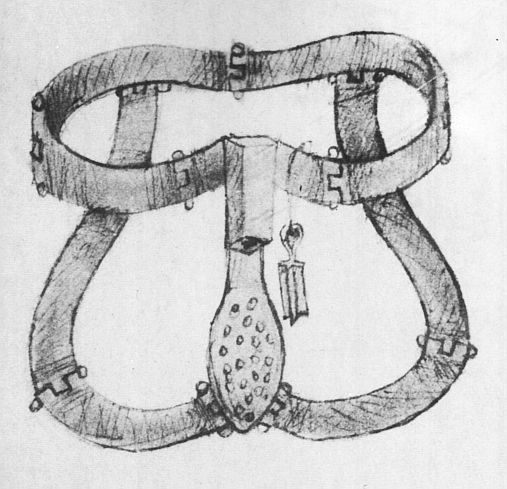

The earliest extant drawing of a chastity belt showed up in 1405, in a work on military engineering called Bellifortis, among detailed designs for catapults, armor, torture devices, and other instruments of war. Here’s how the belt was depicted:

But not everything in the book was serious. Included in the codex are what Classen calls “highly fanciful objects” for making people invisible. The author, Konrad Kyeser, also makes a couple of fart jokes. Though the chastity belt is depicted in a fair bit of detail, no one has ever found a physical example dating back to this period. Most likely, this image, too, is a joke.

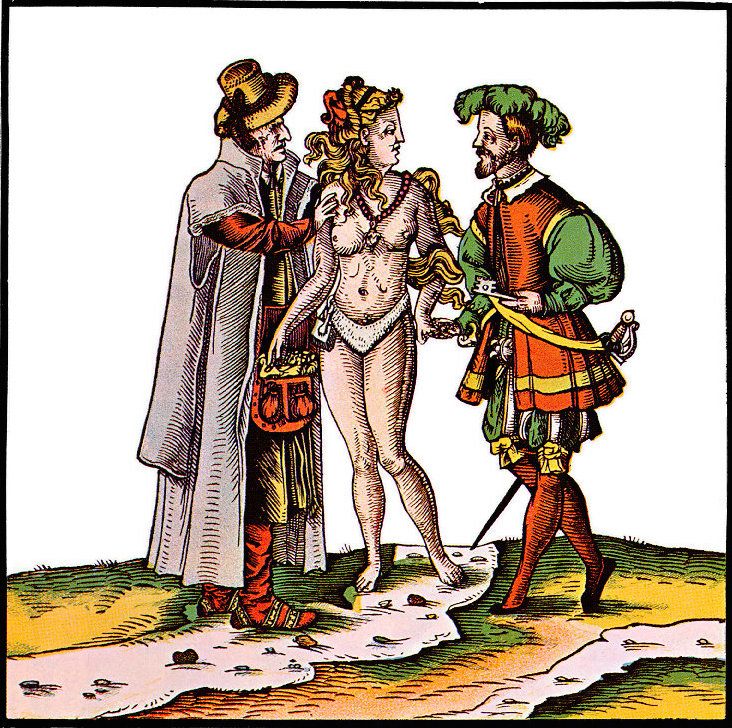

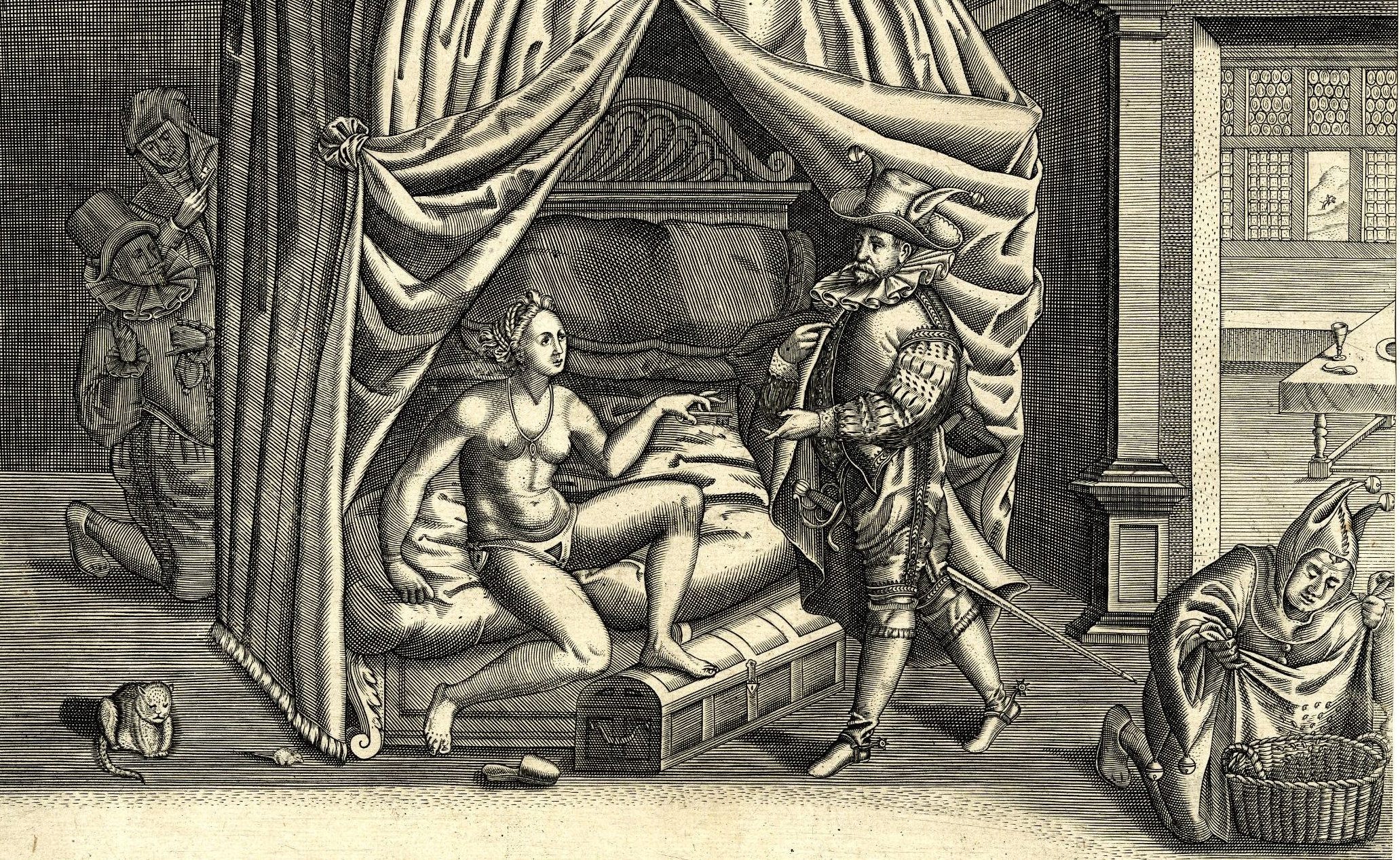

Starting around the 16th century, the chastity belt started showing up more regularly in illustrations, engravings, and woodcuts. Typically, a scene looked something like this. A husband, often an older husband, was leaving on a journey. His wife was pictured, often partially naked, wearing metal underwear. But somewhere in the picture, her lover was already waiting for the husband to leave—with a copy of the belt’s key in hand.

What accounts for the persistence of this story? “Male fear,” according to Classen. “There’s always a lover in the background who already has the duplicate key, he says. In other words, even in the 1500s, no one took the idea of locked-up metal underwear very seriously as an effective anti-sex device. When chastity belts were depicted, it was in the Renaissance equivalent of Robin Hood: Men in Tights—and the audiences for those pieces of art probably thought the idea of a metal chastity belt just as giggle-worthy as late 20th-century teenagers did.

There are physical examples of chastity belts that have been displayed in museums. But most scholars now think that these metal objects were made much, much more recently than the Middle Ages, and are fantasy objects referencing a past that never really existed. Or, as the British Museum puts it: “It is probable that the great majority of examples now existing were made in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as curiosities for the prurient, or as jokes for the tasteless.” (These were the Victorians, after all—obsessed with sex and often very wrong about it.)

One of the examples in Classen’s book, for instance, has a little heart punched out of the metal front, and a hole that’s apparently meant to allow defecation is in the shape of a flower. It’s too cute to be real.

Why has the myth of the chastity belt endured? It’s hard to disprove an idea once it’s firmly lodged in people’s minds. As a result, the same scant information has repeatedly convinced generations that medieval men locked up their wives’ nether regions. Even the practical difficulties of such a device—as one historian wrote, “How could such a mechanism have been designed to permit the normal activities of urination, evacuation, menstruation, and hygiene, yet prevent both anal and vaginal penetration?”—have not dissuaded people from believing in chastity belts.

“People delight in delving into sex. They can say they only have a historical interest, but in reality they have a prurient interest,” says Classen. “It’s a fantasy.”

For men, the chastity belt is a fantasy about female sexual appetites—women are so horny that only locking them up can keep them in check. For women, it’s a fantasy about male cruelty and control. But for many people, it’s simply a fantasy about sex. Even if chastity belts used to enforce medieval fidelity were not real, modern chastity belts, sold as fetish objects, definitely, definitely are.

This story originally ran on August 17, 2015.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook