For Sale: One of the First and Most Valuable Dollars in U.S. History

You’ll need a lot of pretty pennies to buy it.

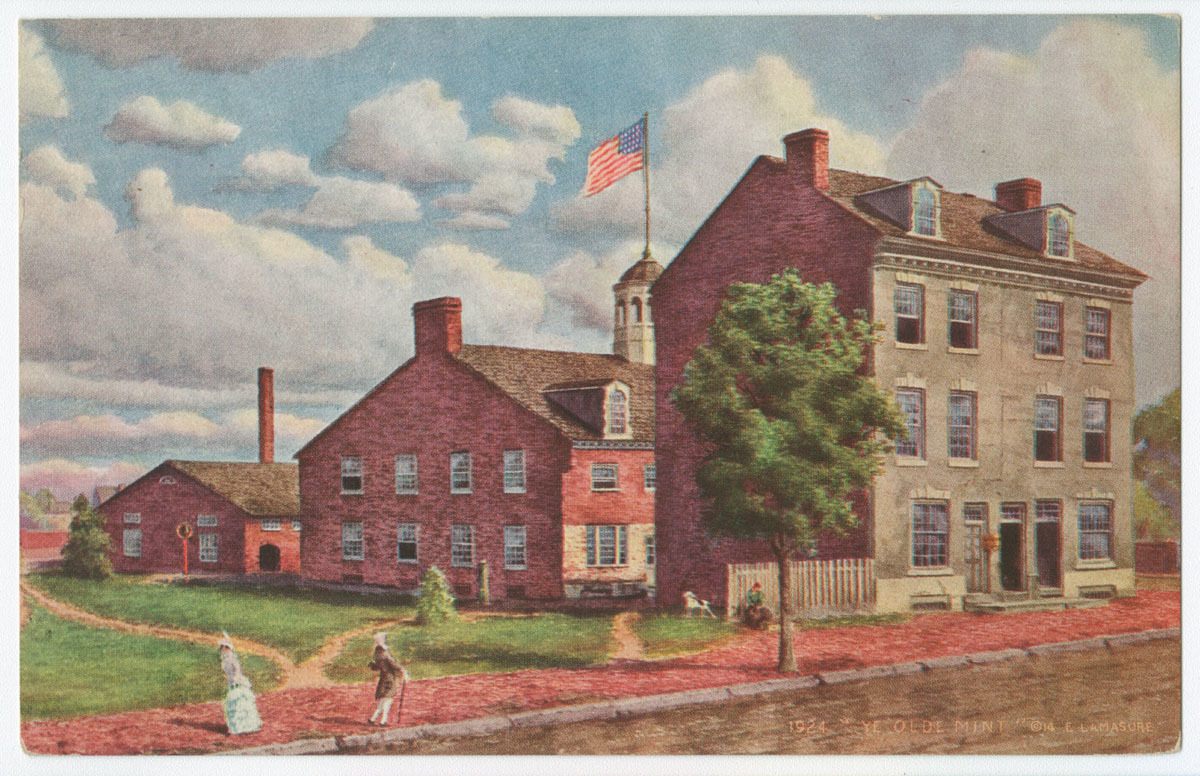

On October 15, 1794, Henry Voigt, the Chief Coiner of the United States, hurried nearly 2,000 silver coins to the desk of David Rittenhouse, the Director of the United States Mint. That day marked a milestone in the making of a country: Two years after Alexander Hamilton established the Mint under President George Washington, the first dollars had been minted.

There’s some debate about what happened next. Some experts say there was a ceremony, well-attended by diplomats and representatives. Others say that despite the historic event, it was all business—no hor d’oeuvres, no party. Still others, including the Smithsonian Institution, say that the coinage was destined for the pockets of the aforementioned dignitaries, as a token of the bright future of the fledgling United States.

What’s certain is that now, over 200 Octobers later, one of those dollars will go up for auction.

“The reason for producing these was to say, ‘We can do this. Let’s get them out to senators, congressmen, and other VIPs, to show them the Mint is moving forward,’” says Douglas Mudd, the director and curator of the American Numismatic Association’s Money Museum. “1794 is the year they say, ‘We’ll start the dollar coin, the linchpin of the system.’ Because our system is built on the dollar, and then multiples of the dollar, and then fractions of the dollar.”

The coins up for auction—15 in total, spanning the decade when this type of silver dollar was minted—are Flowing Hair dollars, so named for the regal mane rocked by the busts on the coins’ front side, or obverse. (On the reverse: a narrow-necked eagle with a furrowed brow.) The antique change makes up the Bruce Morelan Collection, and it’s set to sashay across the auction block in Las Vegas on October 8.

Of particular note is the 1794 one-dollar coin, the most valuable American coin in existence. It last sold for just over $10 million in 2013, usurping the longstanding record-holder, the possibly more-famous 1933 Double Eagle. An 1804 dollar, printed just before the Mint stopped making the coin for over three decades, is also a noteworthy piece.

“The fact that this particular 1794 silver dollar is selling, and the fact that any 1804 dollar is selling, makes this a numismatic event,” Mudd says, using the technical term for the study of coins. “You’re lucky if an 1804 dollar sells every three to four years at most, and this 1794 dollar, because it’s perhaps the first, makes it very special in itself.”

On that mid-October day in 1794, the Mint was still toddling: It lacked a heavy press to mass-produce its coins. The 1,758 dollar coins that Voigt delivered were just an appetizer; the Mint would soon create enough coinage to power one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

The 1794 dollars are valuable in part because of how few are left. Estimates tend to be in the low hundreds, and only a select few ever go to auction. The record-holding 1794 dollar was one of the earliest made, as deduced by the crispness of the coin’s raised edges and lettering, and its “prooflike reflectivity”—a coin so fresh off the press that its flat surfaces could be mistaken for mirrors. (Over time, the “dies” that strike the coins become dulled, softening the features of everything from the Flowing Hair to Kennedy’s chin on the more recent half-dollar.)

The coin that’s now up for auction was apparently cut from the same cloth. “Experts have looked at it and they’ve determined it’s a very early die state,” Mudd says. “It could be the first silver coin struck off the dies. We may never know, unless you have a time machine.”

Before the Mint’s creation, transactions were done through a combination of colonial and foreign currencies and bartering. Even when the first money-making site was up and running in Philadelphia, the Mint struggled with the dollar unit. In early America, dimes made a lot more sense—very few people made a dollar in a day. So in 1804, the coin was temporarily discontinued.

The term “1804 dollar” turns out to be a bit of a misnomer. That year, the Mint was so strapped for cash that it struck dollar coins with a still-usable 1803 die, meaning that dollars made in 1804 nonetheless have “1803” printed on them. Decades later, the Jackson administration resumed the circulation of dollars, and retroactively struck dollars with “1804” on them, as diplomatic gifts to coin-collecting foreign leaders, such as King Rama III of Siam (now Thailand) and the Sultan of Muscat (now part of Oman). So few of the dollars were made, and so private were the collections to which they belonged, that they practically passed into legend—until the King of Siam’s set was sold off, confirming the stories about kingly coin collections housing the rarified coins.

What remains to be seen is whether these coins, especially that very early dollar from 1794, will fetch as princely a sum as the most expensive in history. If the asking price isn’t met for the coins, they will remain in the collection. “The thing it comes down to,” Mudd says, “is that there are two people that want it badly enough.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook