For Sale: Ricky Jay’s One-of-a-Kind Collection of Magic, Mystery, and Masterpieces

The late, legendary magician and actor always followed his curiosity.

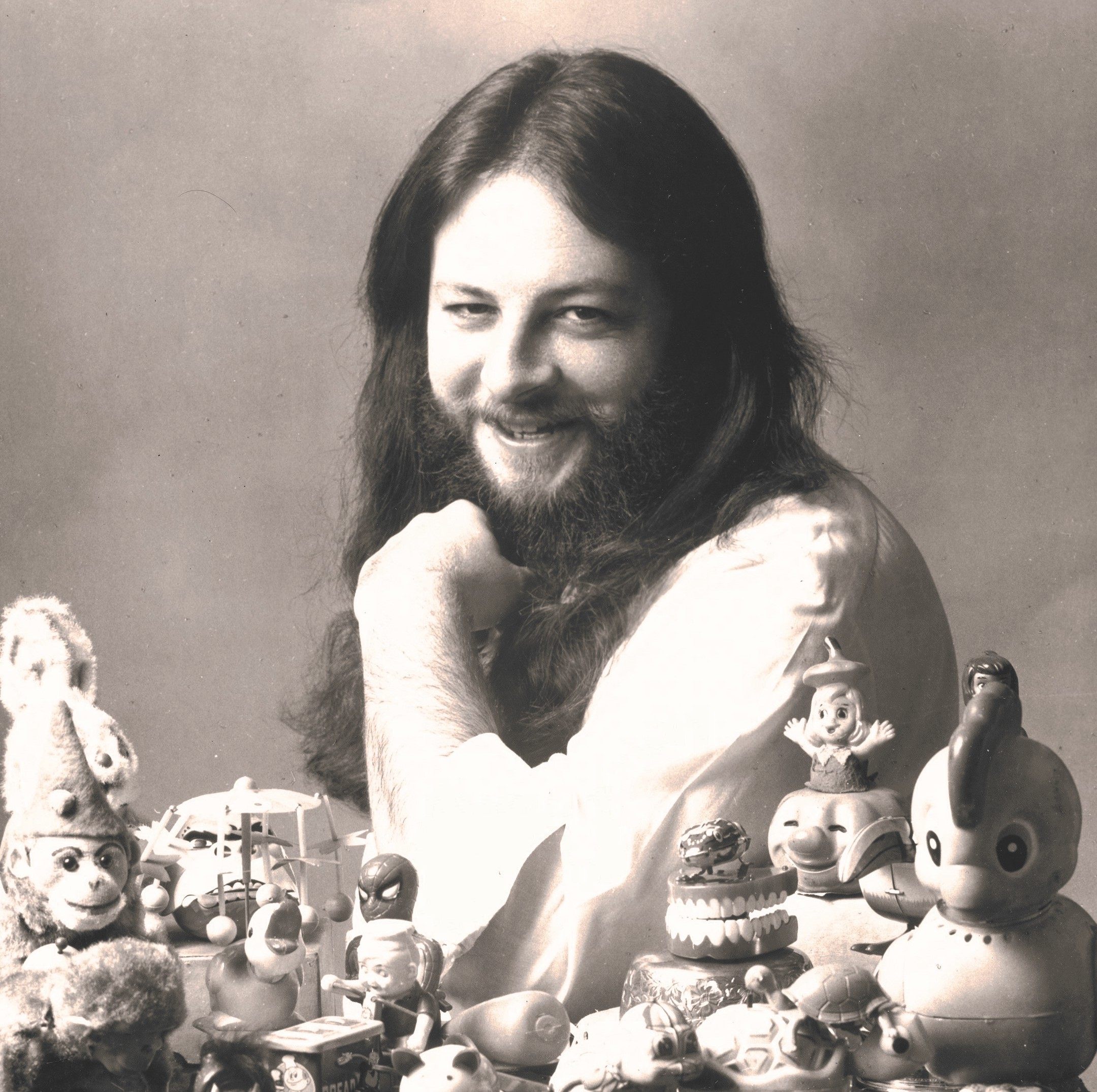

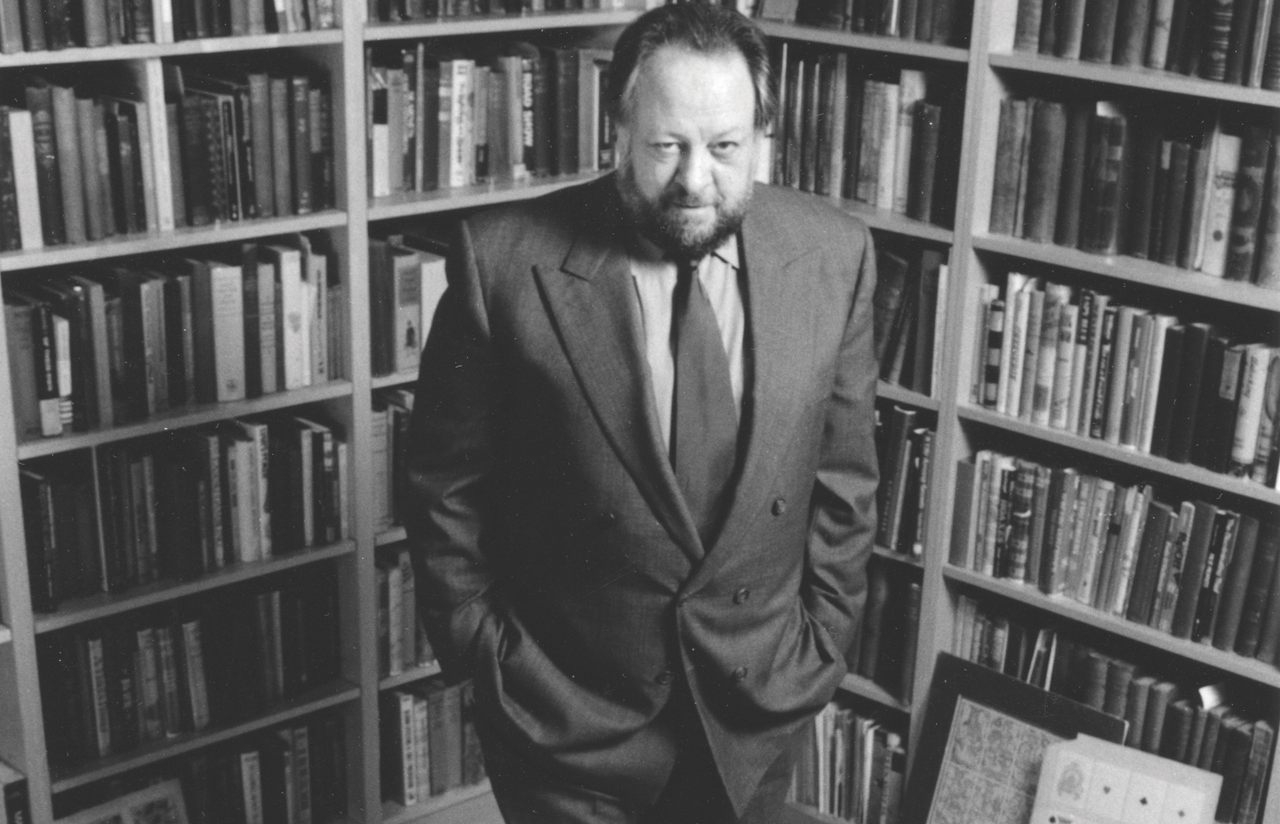

Some knew Ricky Jay as a magician, a renowned sleight-of-hand artist who could manipulate cards with superhuman dexterity. Others discovered him as an actor, in films such as Magnolia or the HBO series Deadwood. What’s more, Jay somehow found time to become an accomplished author—Learned Pigs & Fireproof Women, and Jay’s Journal of Anomalies—guides to the perplexing and chronicles of the world’s more bizarre entertainments.

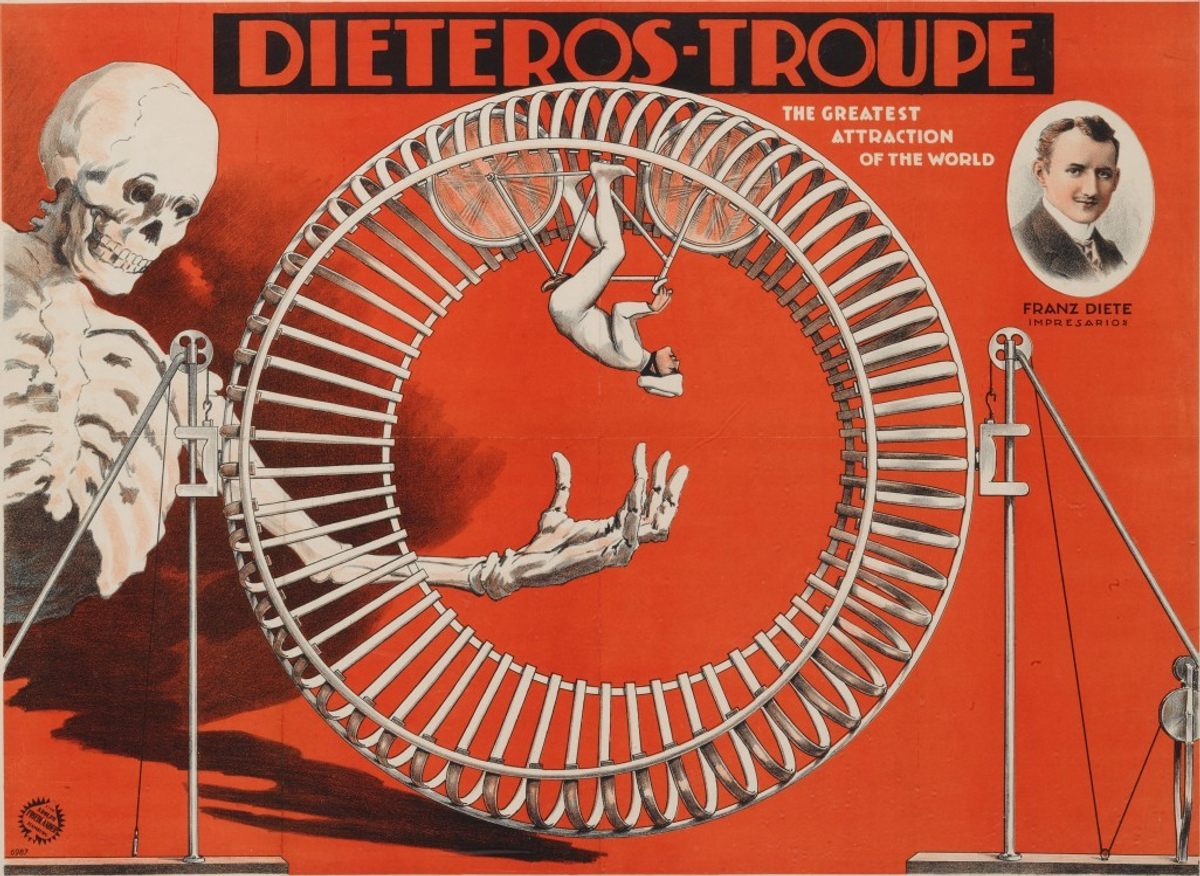

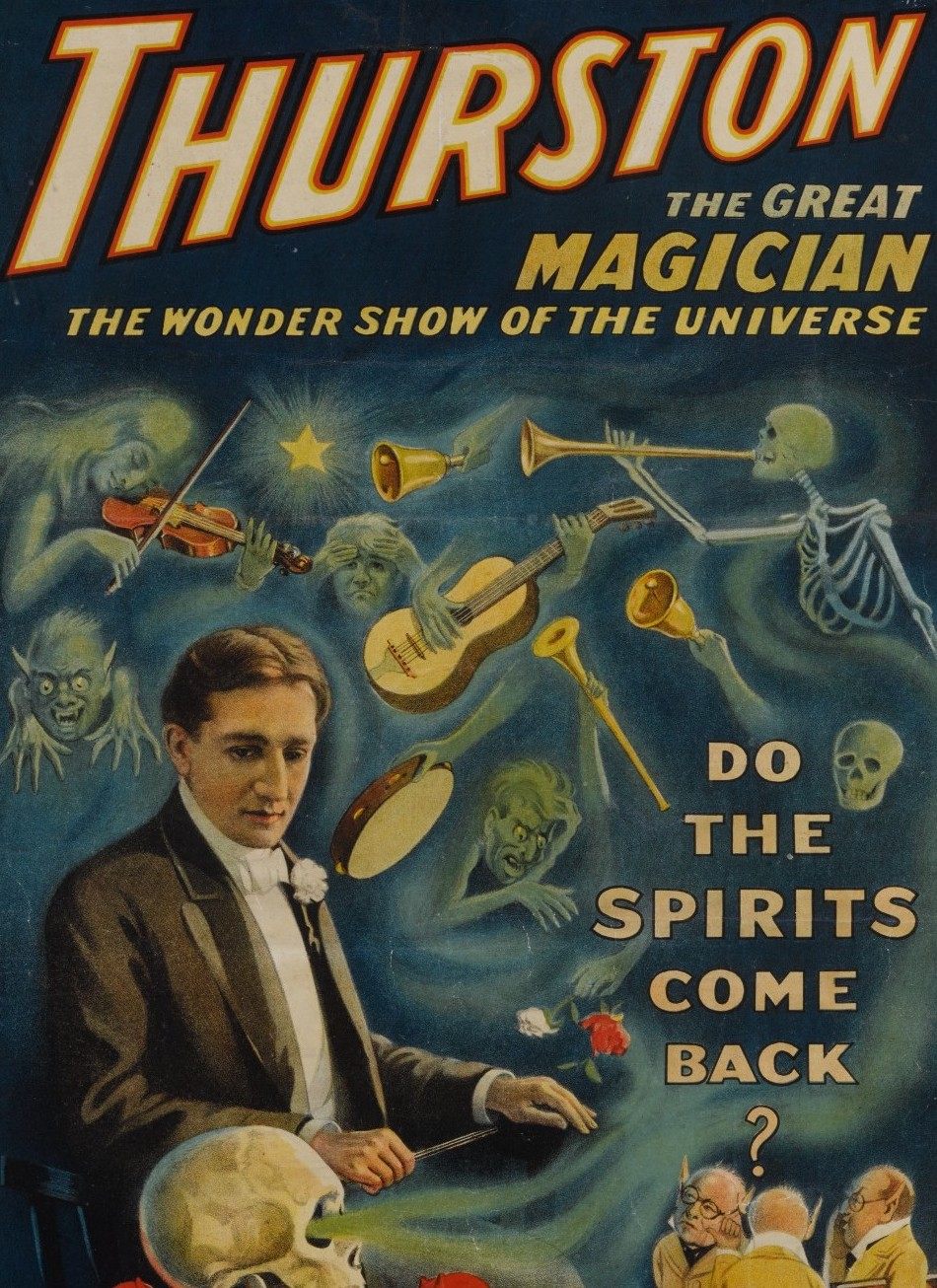

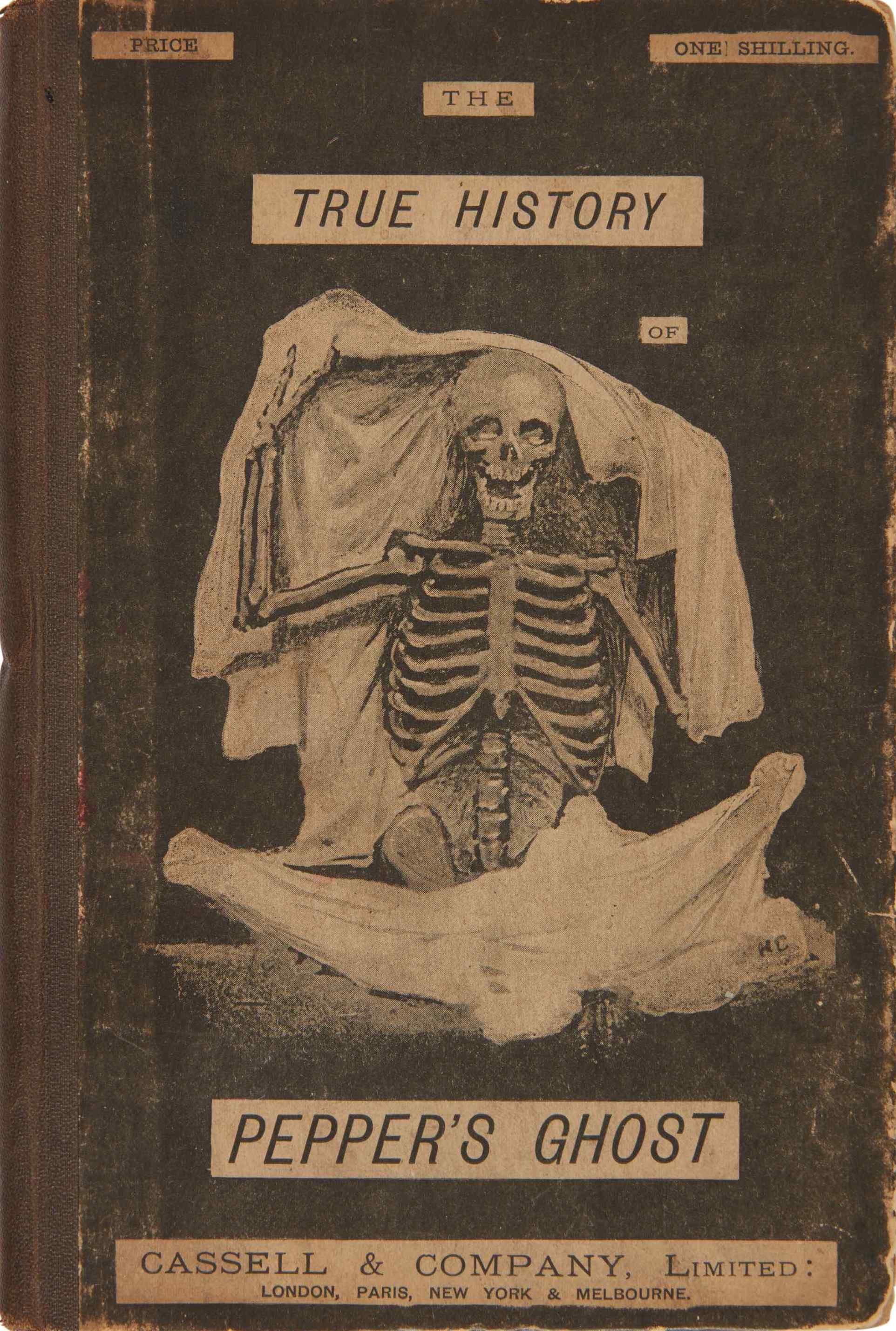

Jay was also—not finally, but in addition—an eminent collector; among the foremost collectors of texts, artworks, and apparatuses related to magic, its history, and all varieties of its curious offshoots. A quick look through Sotheby’s sale of The Ricky Jay Collection—some 634 lots—reveals rare, antique books; historic posters promoting the masters of the magical arts, virtuosic artworks composed of hidden, microscopic writing; an automaton with which Jay performed on stage, and various broadsides claiming to advertise “learned animals,” from a multilingual horse to a card-playing pig. An emporium of the extraordinary, the collection will be auctioned in New York on October 27 and 28, 2021.

Born in Brooklyn in 1946, Jay first performed in public as a magician at the age of four. His grandfather, an accountant named Max Katz, enthused over magic and nurtured Jay’s interest. Katz also personally introduced his young grandson to masters of the old guard such as Tony Slydini and Francis Carlyle. Jay’s first-person immersion in their classical artistry and style of presentation—Al Flosso performed at Jay’s bar mitzvah—made him their torch-bearer among the next generation of conjurers. He viewed the art of magic as sacrosanct and personal, not as merely fun or diverting.

In a lengthy 1993 New Yorker profile, Jay recalled an admirer gleefully explaining that he’d incorporated one of Jay’s routines into his act. “Audiences just love it,” the admirer said. Jay did not. “Suppose I invite you over to my house for dinner,” Jay replied. “‘We have a pleasant meal, we talk about magic, it’s an enjoyable evening. Then, as you’re about to leave, you walk into my living room and you pick up my television and walk out with it. You steal my television set. Would you do that?’ He says, ‘Of course not.’ And I say, ‘But you already did.’ He says, ‘What are you talking about?’ I say, ‘You stole my television!’” When asked why he didn’t lecture at magic conventions, Jay would answer: “Because I’m still learning.” He approached collecting with the same seriousness, through his death in 2018 at the age of 72.

Expected to draw the highest final bid—perhaps six figures—is a collection of nearly 500 portraits depicting “Remarkable Characters,” compiled in two volumes by 19th-century English collector William Esdaile. Among this cast of characters are “Cheats, Forgers, Imposters,” “Bawds & Courtezans,” and more. Focused mostly on the 17th and 18th centuries, the set captures—in one piece—the range of Jay’s interests and the extent of his curiosity. Profiled and portrayed therein are “Murderers” such as Elizabeth Brownrigg; “Curious Poetical Genius’s” such as Phillis Wheatley, the first Black American woman to publish a book of poetry; and, delightfully, “Persons Remarkable for One or More Circumstances of their Lives,” including a London-based manufacturer of razor-sharpeners and Mother Damnable, who ran a brothel in 19th-century Seattle.

The book’s categorial thesis is confounding: Why associate murderers with poets, or even “Persons Remarkable” for completely different “Circumstances of their Lives”? In its messiness, however, it clarifies something essential about Jay. His fascination was simply with the fascinating—whatever form that might take.

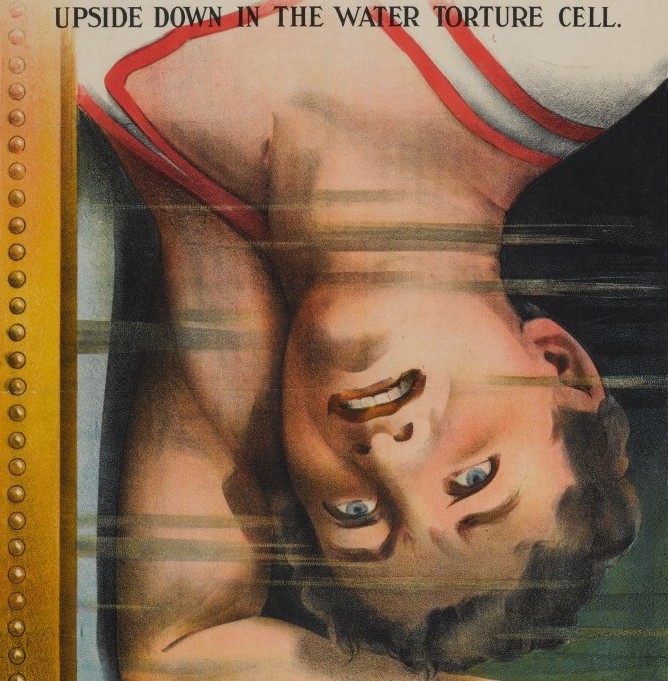

Jay’s collection also boasts a considerable amount of Houdiniana, including a poster depicting the escape artist’s “most famous, dangerous, and dramatic” escape from the Water Torture Cell; slides Houdini used in a touring lecture that asked, “Can the Dead Speak to the Living?” (his conclusion: no); and a book off of Houdini’s own shelf, containing his annotations. One hopes that the next owner will also be a legendary magician, to keep the chain intact.

Though Houdini may be the marquee name from Jay’s collection, few historical figures captured Jay’s imagination like Matthias Buchinger. Born near Nuremberg in 1674, Buchinger mastered the impossibly intricate art of micrography—microscopic writing that forms a larger image—even though he was born without hands or feet. Standing 29 inches tall, he traveled through Europe, dazzling audiences not only with his drawings, but also with his abilities on several musical instruments, and, of course, with magic tricks. Jay spent years searching for Buchinger’s elusive works and building a collection. He even documented the chase in a 2016 book, Matthias Buchinger: “The Greatest German Living”. Its publication coincided with an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, entitled Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger’s Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay.

The auction includes a full 39 items by or about Buchinger, one of which—a possible forgery—Jay pursued for over 20 years. For an authentic appreciation of Buchinger’s virtuosity, meanwhile, look no further than his 1718 portrait of the late Queen Anne. The curlicues surrounding the Queen’s portrait are, in fact, three chapters from the Book of Kings, manually rendered at near-microscopic scale. Using just his appendages, Buchinger achieved a similar effect in the family trees he drew, such as this one, in which the fruits contain not only names, but also detailed accounts of the family’s history. A handbill announcing a Buchinger visit to London, also for sale, claims that “all that see him, say, he is the only Artist in the World.”

It was not unusual for similarly high praise to be showered upon Jay himself. In the New Yorker profile, journalist Mark Singer described Jay as “perhaps the most gifted sleight-of-hand artist alive.” Molly Bernstein, director of the 2012 documentary Deceptive Practice: The Mysteries and Mentors of Ricky Jay, recalls attending a performance of “Ricky Jay & His 52 Assistants,” Jay’s hit card-magic show, in New York in 1998. There were “lines around the block, even in snowstorms” to get tickets, says Bernstein. She was struck by seeing people in “a sophisticated, adult, New York audience” who were literally “gasping” at the magus’ sleight of hand.

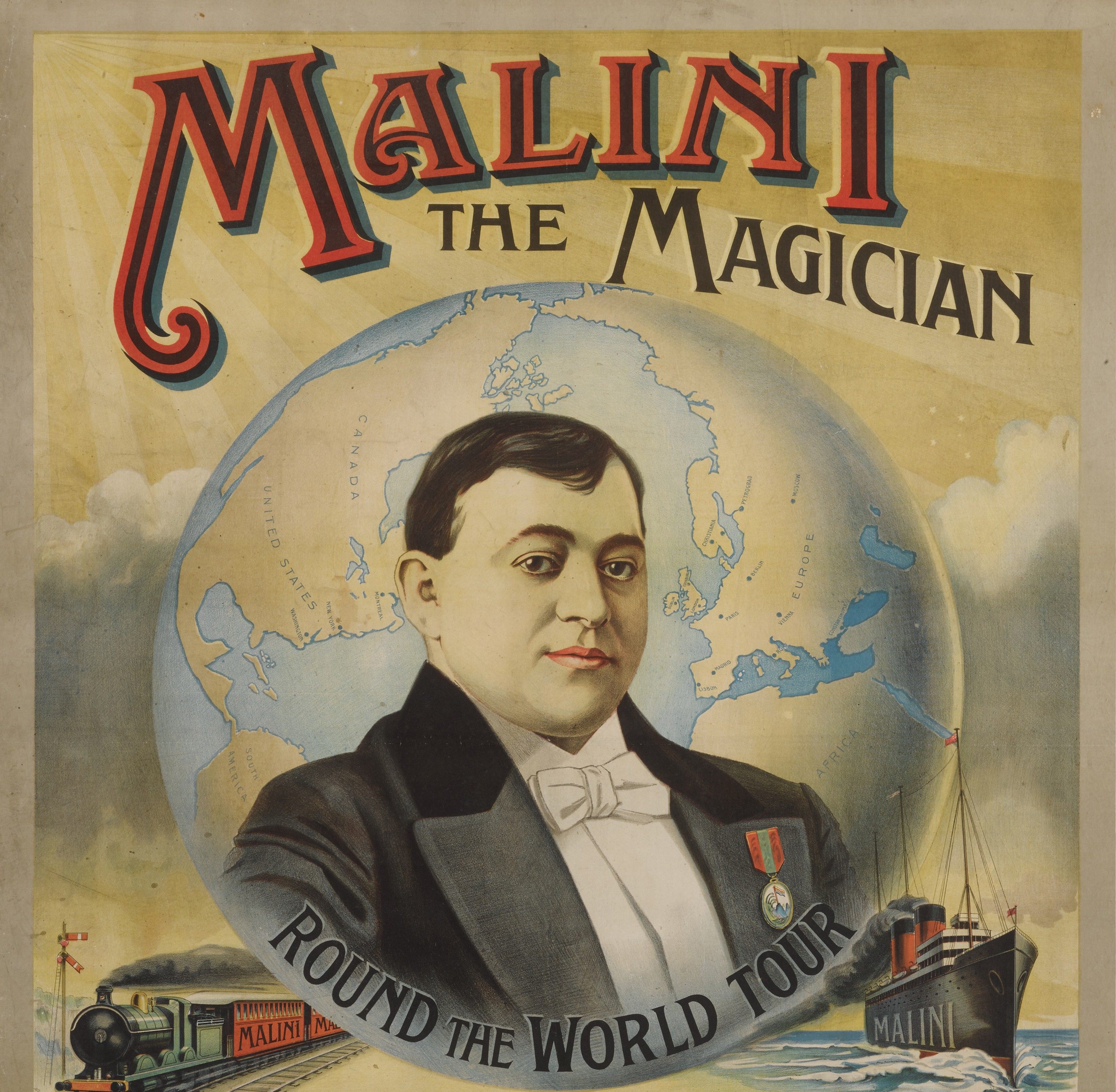

In Deceptive Practice, journalist Suzie Mackenzie recalls going to lunch with Jay in 1995, on assignment to interview him for The Guardian. He began to tell her about a signature trick done by one of his greatest influences, Max Malini, who could make a large block of ice appear under his hat while seated at a dinner party.

“He started to tell me the story of Malini at the dinner party,” Mackenzie remembers. As he spoke, she became aware that he had his tall lunch menu open in front of him. As he spoke the words, “and Malini lifts up the hat,” Jay lifted his menu, revealing a huge block of ice. “I mean it was about a foot square,” Mackenzie said, her voice quavering. “Later, when I picked it up, held it with two arms, I remember I burst into tears. And I think that shocked him a bit, actually. Cause it was such a kind of violent reaction—you know, I just sobbed …”

Jay attempted to console her: “I deceived you, it’s what I do for a living.” But for Mackenzie, it was beyond sheer deception or entertainment. “I mean, it’s a moment I’ll never have again,” she said. “I’ll never forget it. I mean, it was a kind of supreme piece of artistry, that I witnessed, that was done for me. That’s what it felt like at the time. He had produced this extraordinary effect for me.” She explained that it was a “fantastically hot” day, with the sun beaming through the restaurant’s glass walls, and that the ice was melting fast in front of her. “It was the most extraordinary thing I’d ever seen in my life,” she said. Part of what made it so, in her telling, was its generosity. Bernstein says that that was the only time that Jay ever performed Malini’s ice block deception—in private, for an audience of one.

“It’s a little sad looking at all this stuff” up for auction, says Bernstein. She remembers seeing it meticulously arranged in Jay’s home library.

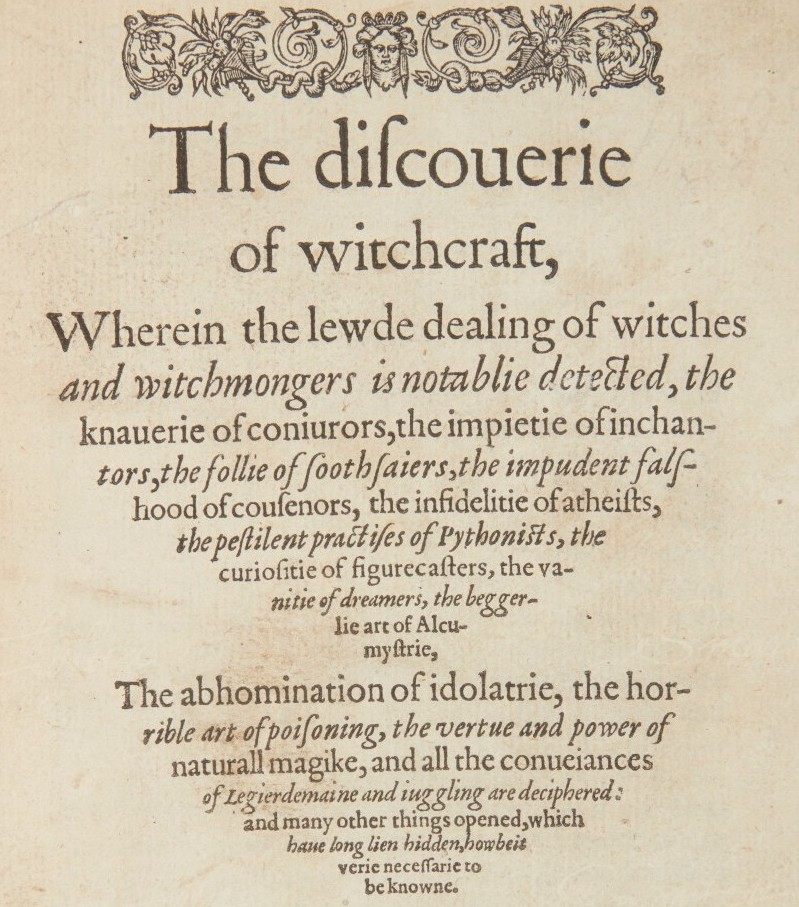

One of the rarest items from that library, now one of the auction’s top lots, is a first edition of Reginald Scot’s 1584 treatise, The discoverie of witchcraft. In it, Scot lays out his theory debunking the existence of real witches: If something bad happened after a begging woman was denied assistance, people would attribute it to a curse she had cast. She had no actual magic powers, Scot insisted; people just believed she did.

There’s something interesting about a magician like Jay acquiring this book, which might seem to undermine the credibility of the profession. But as Jay admitted to Mackenzie, he “deceived” her—he did not claim to literally conjure the ice out of thin air. Magic may not be supernatural at all, but in the hands of a virtuoso like Jay, it is a high art, an essentially, sublimely, human form of expression.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook