The Damnable Dames Who Helped Shape Seattle’s Character

The madams of Puget Sound were spitfire entrepreneurs who lived dangerously and died young.

A group of women, thought to include Lou Graham, at a Seattle brothel in the late 1800s. (Photo: Public Domain)

The names Mother Damnable and Zella Nightingale may not sound like they belong in Seattle’s municipal history books, but these two high-spirited madams, and many more like them, played a significant role in shaping the character of the city.

Seattle began its life in the mid-19th century as a timber port. Young men flocked to the city to mine, log, and fish the waters of Puget Sound. Though natural resources were plentiful, the new residents noticed a troubling shortage of female companions—a lack of amenities and the dangerous conditions of the West Coast didn’t appeal to the civilized women back east.

Fortunately for the settlers, a handful of ruthless, ambitious pioneer women saw the scarcity and sought to fill it—for a price. These ladies started gentleman’s clubs, crib houses, and brothels in Seattle’s red light district, sometimes called the Tenderloin, Lava Beds, or Skid Row, and became some of the most prominent residents of the fledgling city, using the lawless, trailblazing spirit of the Wild West to write themselves into the history of early America.

Men cutting shingle bolts near Seattle. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-67618)

The first of these ladies was Mary Ann Conklin, born Mary Ann Boyer in Pennsylvania in 1821. She married the captain of a whaling ship, David “Bull” Conklin. After a falling out, he stranded her in Port Townsend, a settlement 50 miles northwest of Seattle. Thus ditched, Mrs. Conklin trekked solo to Seattle to eke out a living on Puget Sound.

Mrs. Conklin was hardly a damsel in distress. Soon after she was abandoned she became the manager of the Felker House, a hostel owned by Captain Leonard Felker. Her sailor’s tongue and hot temper were renowned by travelers throughout the West Coast. Seattleites began to call her Mother Damnable (later Madame Damnable when she opened a brothel above the hotel), claiming that “her profanity was equally colorful in English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Portuguese, and German.”

In her hostessing, Mother Damnable was as fiery as she was ambitious. Any unused rooms at the hostel she rented to the Territorial Court for $25 a day—the equivalent of about $750 today. She was reported to have defended Felker’s private garden from soldiers looking to build a road during the 1856 Battle of Seattle by loosing attack dogs and throwing rocks at the construction crew. She became such a prominent figure in the city that Felker’s hotel came to be called the Conklin House, or Mother Damnable’s, by residents.

After her death in 1873, Mother Damnable was buried in the Lakeview Cemetery in Seattle. Ten years later, contractors responsible for relocating the deceased dug up her casket and discovered that it weighed at least 400 pounds. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported these eye-opening details in 1884:

on removing the lid to the coffin we found that she had turned to stone. Her form was full sized and perfect, the ears, finger nails and hair being all intact. Her features were, however, somewhat disfigured. Covering the body was a dark dust, but after that was removed the form was as white as marble and as hard as stone.

Local historians use her calcification as proof that her notorious hard-headedness was severe enough to live on after her death.

Just after Mother Damnable’s passing, a new madame turned up in Seattle. Lou Graham, born Dorothea Georgine Emile Ohben in Germany in 1857, arrived in Seattle in 1888. The city had just experienced a period of reform due to the institution of women’s suffrage, and the economy had tanked due to the mass closure of brothels and revoking of liquor licenses. Graham, then a prostitute, saw the depleted economy and lack of competition as the perfect business opportunity. She approached banker Jacob Furth and a number of other prominent businessmen for funding to start a high-end brothel on the corner of Third and Washington, in what is now Pioneer Square.

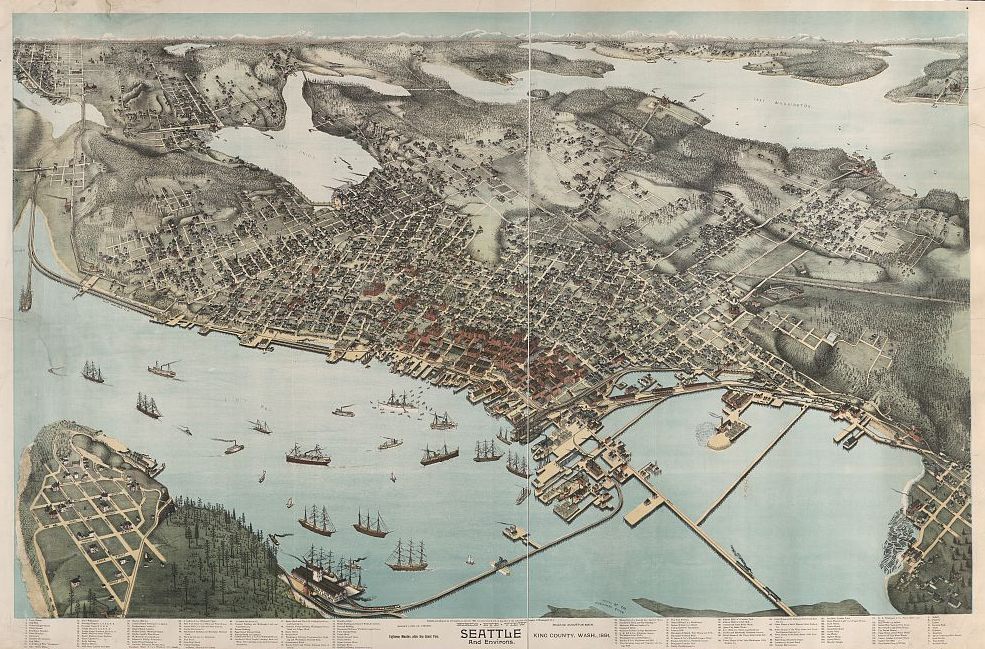

An aerial view of Seattle, 1891. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-10761)

Graham imagined a brothel that cost as much as the finest hotels, and provided high-profile businessmen with the company of the most beautiful, educated and cultured women in the city. She offered comparatively safe living quarters and schooling for her employees. Though her brothel burned in the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, she had already made enough profit to rebuild a larger, stone building on the property long before other businesses recovered from the disaster.

Seattle historian Bill Spiedal describes Graham as “regal.” She wore plumed hats, traveled in elegant carriages, and “stood for integrity in her field … and a kind of class that couldn’t be matched outside of the other major cities of the world like San Francisco, New York, London, Paris.” Graham provided high-interest loans to entrepreneurs, invested heavily in the stock market, and soon became one of the city’s richest residents. Perhaps because of her wealth, or perhaps because of rumors that “the pleasures of her house were free to government officials,” Graham weathered a series of morality campaigns in the city, shutting down for only days a time before promptly reopening her doors.

Graham left Seattle in 1902, after particularly stifling laws were put in place that made it difficult to perform business. She traveled to San Francisco and died two months later of mysterious causes—newspapers reported an ulcer as the cause of death, while other accounts claim she died of suicide, drug overdose, or syphilis. Before her death, she contributed huge amounts of money to city projects and children’s education, and saved many wealthy families and their businesses from bankruptcy.

The Washington Court Building in Seattle, former site of Lou Graham’s brothel. (Photo: Joe Mabel/CC BY-SA 3.0)

These celebrated madams paved the way for later figures—Nellie Curtis started her career by opening the Camp Hotel in 1933. She later purchased the LaSalle, a 57-room majesty on Pike and First, from the Kodama family when the government placed them in interment camps in 1942. Curtis had as many as aliases as she had costumes, going by Zella Nightingale, Yetta Solomon, and Nellie Gray, among others. She was said to rent two rooms in the hotel: one to keep her hats in, and the other for her money.

In the 1950s, Nellie left Seattle to open the Curtis Hotel in Aberdeen, a small city in Grays Harbor county. Nearby, another historical madame, Ruth Rucker, was operating a number of crib houses in Centralia, Washington. Rucker married the police chief of Centralia, who helped control prostitution and bootlegging operations in the small town while his wife helped down-on-their-luck women earn money in a way that maintained their dignity and decorum. A burgeoning entrepreneur and champion for working girls at a time when women still could not own businesses, Rucker was a free-spirit who had six lovers at the time of her death in 1978.

Though major figures in a dark and still troubling history, Seattle’s first ladies were spitfire entrepreneurs who lived dangerously, died young, and transformed themselves into opulent society women along the way. It can be a challenge to separate their biographies from their mythic reputations, but the ambition and business-sense that drove these women to fame and fortune, and the contribution they made to the early history of the region, remains indisputable.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook