The Novel That Imagined a Nazi Future, Before WWII Even Began

In the long-forgotten “Swastika Night,” Hitler is a god, women are subhuman, and love is dead.

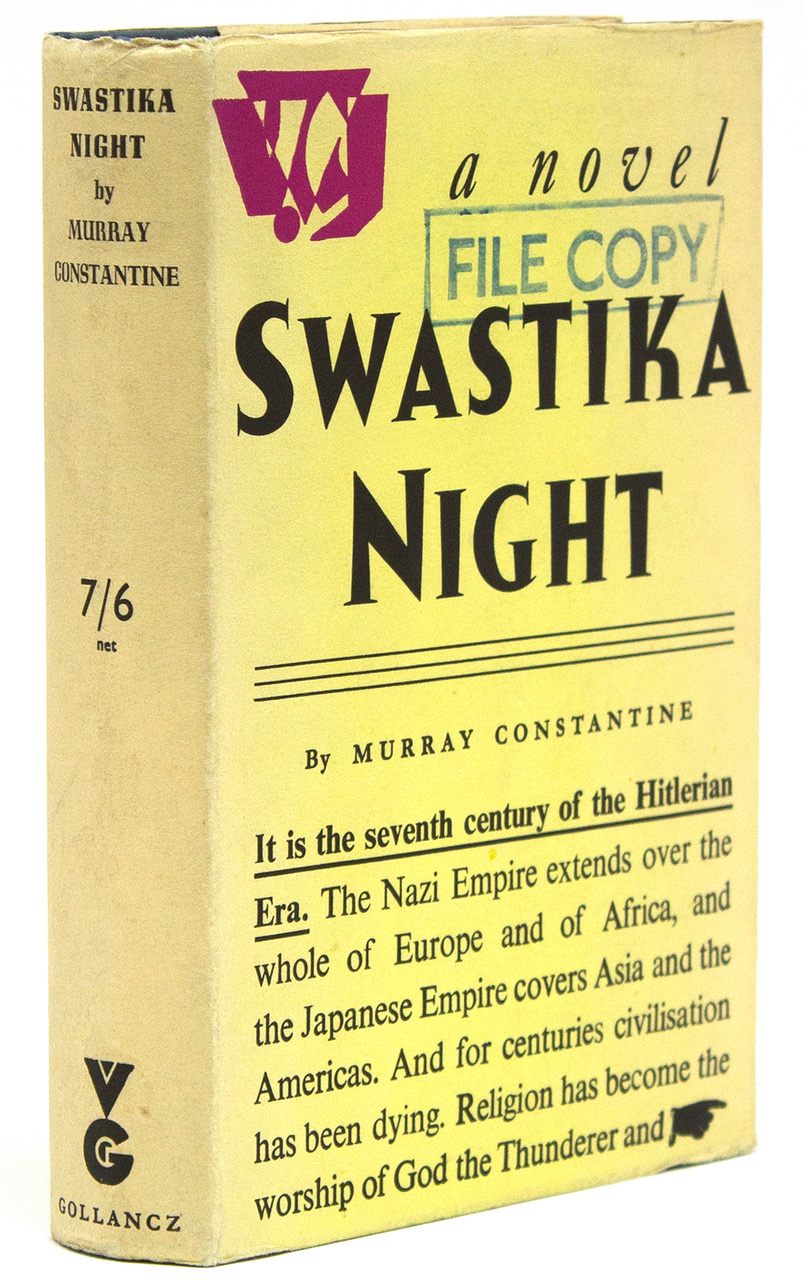

The most remarkable thing about the book Swastika Night is the fact that it was published in 1937. Neville Chamberlain was still pursuing a policy of appeasement toward Germany and its führer, and war was still a couple of years away. But British writer Katharine Burdekin was already imagining a future 700 years after the Nazis had triumphed and the world was divided into spheres of German and Japanese influence.

In this future, Hitler is considered divine, and women are considered less than human—little more than “talking animals,” as one character puts it. Writing under the pseudonym Murray Constantine, Burdekin laid out the dangers of racial and male superiority, not just for non-Germans and women, but for even the most privileged men.

This month, the book will be featured in the first exhibit of speculative fiction at the Grolier Club, a New York society dedicated to book arts and book lovers, alongside classics including H.G. Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau and a first American printing of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Works of speculative fiction—especially alternative histories—usually reveal some deeper anxiety from the time of their creation. But Swastika Night, which was forgotten for most of the 20th century, has an unusual resonance with the late 2010s, when the concerns of the 1930s—authoritarian leaders, racial ideologies, and the nexus of sex and power—have been reanimated.

The book begins in the “Holy Hitler chapel” of a swastika-shaped church. Hitler has become a religious icon, portrayed as a towering paragon with blue eyes and long, golden hair, who was “not born of woman” but exploded fully formed from the head of God the Thunderer. Sometime in the decades after winning what they call “The Twenty Years War,” the victorious Germans realized that it would be easier to control their subject populations with religion rather than force (although force is omnipresent, too). Their society has been organized into rigid strata. At the top are Knights, the direct descendants of 3,000 men handpicked by Hitler. Below the Knights are all other male Germans, known as Nazis, and below them are foreign-born, male “Hitlerians.”

Below all men are women, who live in separate, caged-off districts. At their religious services, they are indoctrinated on two main points: They should never oppose any man (rape, as a concept, no longer exists), and they must hand over their male babies without fuss. The book’s hero, Alfred, an Englishman on a pilgrimage to Germany, is a free thinker who does not believe that Hitler is a god or that Germans are superior to him. But even he has not considered the possibility that women are worth a second thought.

While there had been short-lived rebellions of Englishmen and Scotsmen hundreds of years prior, most people have adapted to this society. Within its rigid system, the state provides housing, food, and care in old age. Men like Alfred can afford small luxuries—the occasional cigar, perhaps—and don’t need to worry about the basics of survival.

But when Alfred meets the Knight Friedrich von Hess, who has his own secret ideas about their society, the limits of racial and male superiority, even for those at the top of this pyramid, start to become clear. This isn’t a subtle book, and that point is made most explicit when von Hess explains that, under German rule, no one —not even Knights—has been able to write new music (at least none that’s any good) or make new art. The structures that give men power bind them too.

Burdekin was born in 1896 in Derbyshire, England. Her parents wouldn’t allow her go to Oxford, as her brothers had, so she married an Olympic rower, had two daughters, immigrated to Australia, started writing, left her husband, and then returned to England. The 1930s were her most fecund creative period, when she wrote 13 novels, six of which were published. She was interested in rationality, time travel, and gender; her book Proud Man features a time-traveling hermaphrodite. Her earliest works were published under her own name, but Murray Constantine appeared in 1934, as her work became increasingly political, to protect her from any blowback. Murray’s identity wasn’t discovered until the early 1980s, when literary scholar Daphne Patai badgered the original publisher of Swastika Night into revealing the book’s true author.

Swastika Night has some obvious successors, notably George Orwell’s 1984, published 12 years later, Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. In Burdekin’s imagined future, though, women are so beaten down that they wouldn’t be able to rebel, as Atwood’s Offred does. Their resistance, such as it is, is biological. They have stopped giving birth to female babies, threatening the end of the German race altogether.

Burdekin’s strength lies in her understanding of the powerful lure of ideology and the deeper threats it can pose. After losing the war, Alfred muses, people found it easier to believe they had succumbed to a god, rather than armies of mere men. Only after 700 years have German subjects started to build up the strength to question those somehow comforting beliefs. And men—not just Knights, but Nazis, Hitlerians, and even persecuted Christians—had accepted the proscription of femaleness, he thinks, because they already believed that women were only “a reflection of men’s wishes.” Even the women, it becomes clear, assisted in their own diminishment: “They thought that if they did all that men told them to do cheerfully and willingly, that men would somehow, in the face of all logic, love them still more,” von Hess explains.

Instead, love has become impossible, and this is Burdekin’s key point. Living in a totalitarian society might not seem so bad, even to those on its lower rungs. But by exalting one group into power (and that group could be female—in another book, The End of This Day’s Business, Burdekin creates a parallel suffering society dominated by women) the possibilities of human life, for everyone, become smaller.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook