Francisco Hernandez: The Coolest Explorer You’ve Never Heard Of

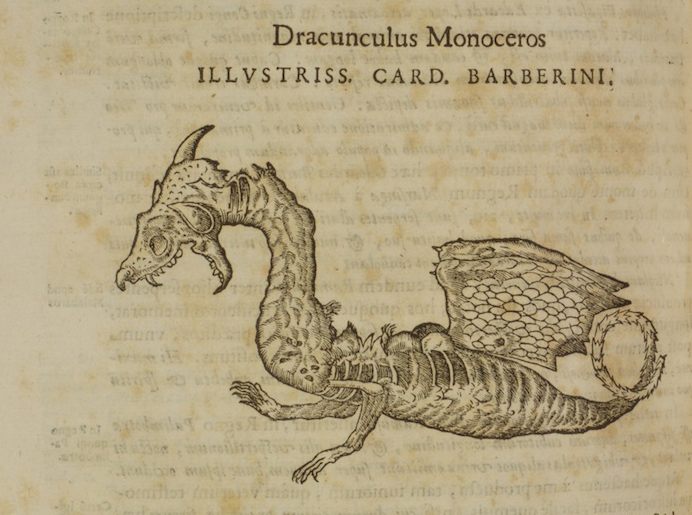

An illustration of a dragon, from Francisco Hernandez, “Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia”, Rome, 1651. (All Photos: Courtesy the History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries)

An illustration of a dragon, from Francisco Hernandez, “Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia”, Rome, 1651. (All Photos: Courtesy the History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries)

In the era right after Columbus, most people who traveled from Europe to the Americas had very specific agendas. They wanted money, or power, or land. And those are the names we know—Cortes, Pizarro, Cordoba; the ones who killed and stole and enslaved in order to bring their home countries a slice of that New World pie.

By contrast, Francisco Hernandez’s name may not ring any bells—but his contributions were just as important, and a lot less bloody. Hernandez was the first European scientist to visit the Americas. With the help of the Aztecs, Hernandez traveled through Mexico in the 1570s, describing and illustrating thousands of species previously unknown to Europe. Some credit him with introducing the continent to everything from corn to cocoa. He is, indisputably, one of the fathers of natural history.

But Hernandez’s extensive work was nearly lost to time. In a new exhibition, called “Galileo’s World,” the University of Oklahoma details how a bunch of intrepid scientists, including Galileo himself, rescued the seminal work from obscurity.

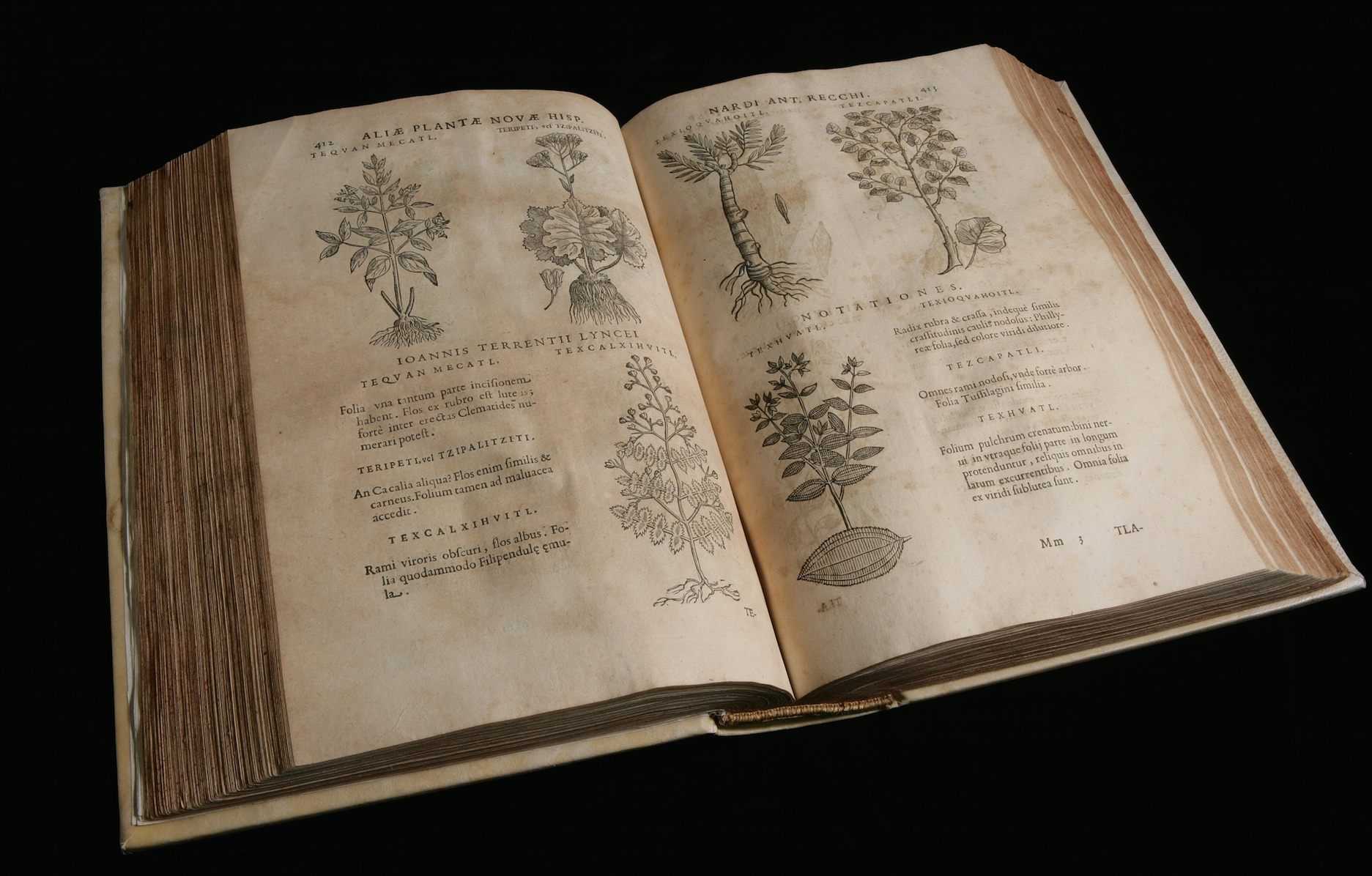

Francisco Hernandez’s ”Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia”, Rome, 1651.

Francisco Hernandez’s ”Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia”, Rome, 1651.

Francisco Hernandez was a doctor and botanist who worked in Spain in the middle of the 16th century. Ambitious by nature, he spent the early years of his career moving from city to city trying to make a name for himself. Eventually, his Spanish translation of Pliny’s classic Natural History gained him some renown, and he became the personal physician to King Philip II.

Philip II, also known as Philip the Prudent, ushered Spain into its Golden Age and was always trying to expand the country’s knowledge and power. In 1570, less than a century after Columbus first set foot in the Bahamas, Philip commissioned his trusted doctor to head over to the New World and put together a complete record of plants and animals.

This was to be the first time any European embarked on a scientific mission there, and Philip expected to find things that would awe his continent. He was heavily invested in the expedition—the level-headed king spent 60,000 ducats on the mission, enough, at the time, to send a thousand soldiers on a year-long campaign.

An impressive New World bird.

An impressive New World bird.

Hernandez and his son Juan left Spain in August of 1571, and touched down in Veracruz the next February. The exploration team of translators, botanists, and geographers hiked through Mexico for three years, collecting specimens, interviewing Spanish colonists and native Nahua residents, and undertaking medical studies.

They hired three indigenous painters, named Antón, Baltazar Elías and Pedro Vázquez, who turned the team’s collective findings into colorful illustrations that Hernandez could later use for reference.

The trip was a smashing success. Over three years of constant travel, and three more years working in a Mexican hospital, Hernandez found and recorded thousands of plants and animals previously unknown to European science. He discovered staples from peyote to pineapples, and shed new light on those that had been introduced but remained mysterious, like cocoa and corn.

When he sailed back home to Spain in 1577, his ship was loaded with seeds, specimens, and a multivolume set of carefully illustrated notes.

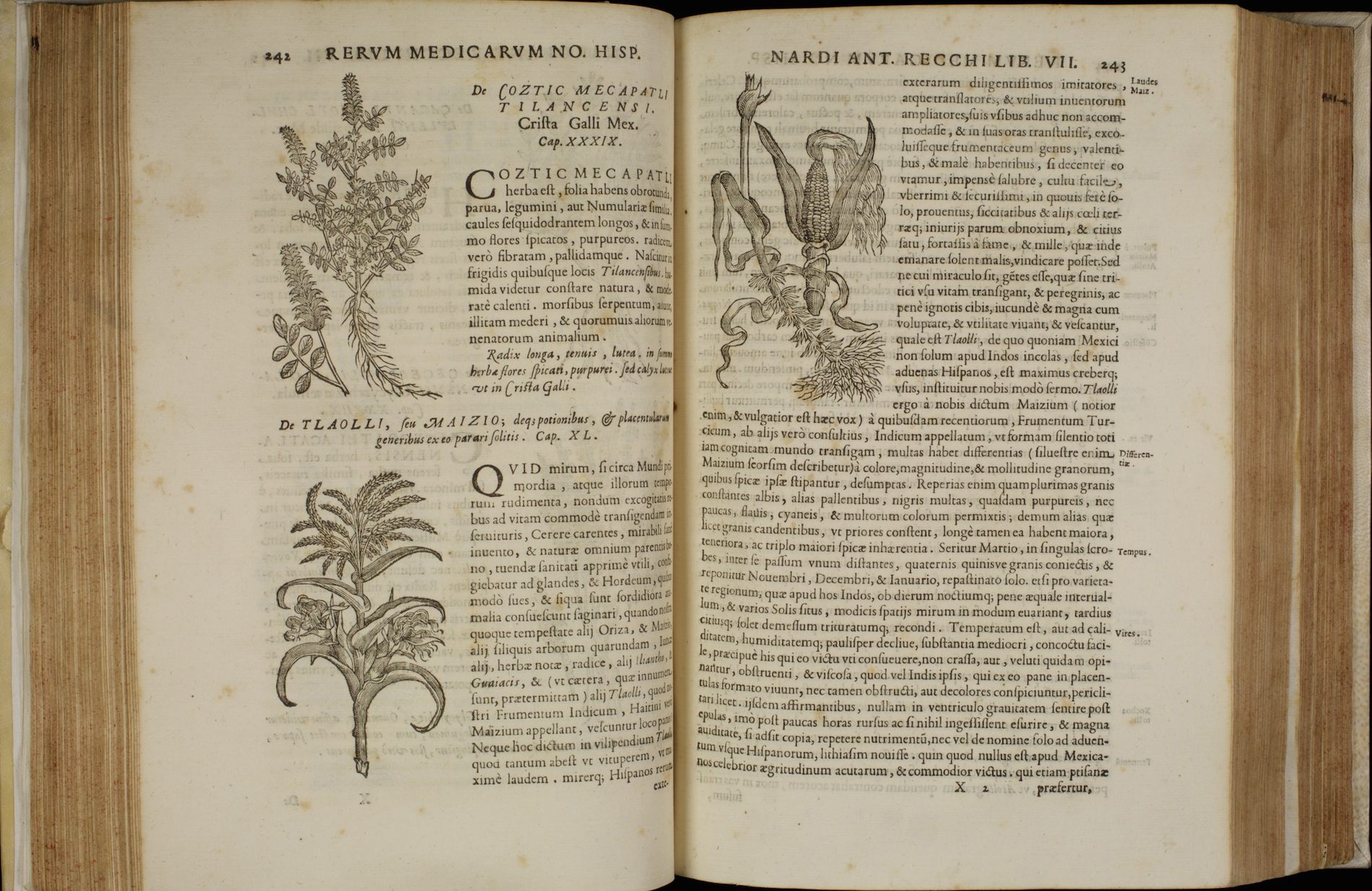

Hernandez introduced all of Europe to corn.

Hernandez introduced all of Europe to corn.

When he arrived home, Hernandez set to work making sense of his manuscripts, with the goal of eventually publishing a Pliny-level magnum opus. But by his death in 1587, he hadn’t gotten very far at all. Philip II, who wanted maximum return on his investment, appointed another court doctor, Nardo Antonio Recchi, to finish the job.

But the papers were pretty confusing, especially for someone who hadn’t been there during the research. When describing the array of new species, Hernandez had kept their original Nahuatl names—both out of respect for the people who had taught him about them and because, in many cases, they were different enough from anything he’d seen in Europe that he wouldn’t have known how to start fitting them into the pantheon.

Although he got a Spanish version of the text published in Mexico, Recchi also died without having made much headway. Soon Philip II died, too, and it looked like Hernandez’s manuscript, rather than open up a new frontier for European life sciences, might remain scattered among different collectors and scholars, lost to history.

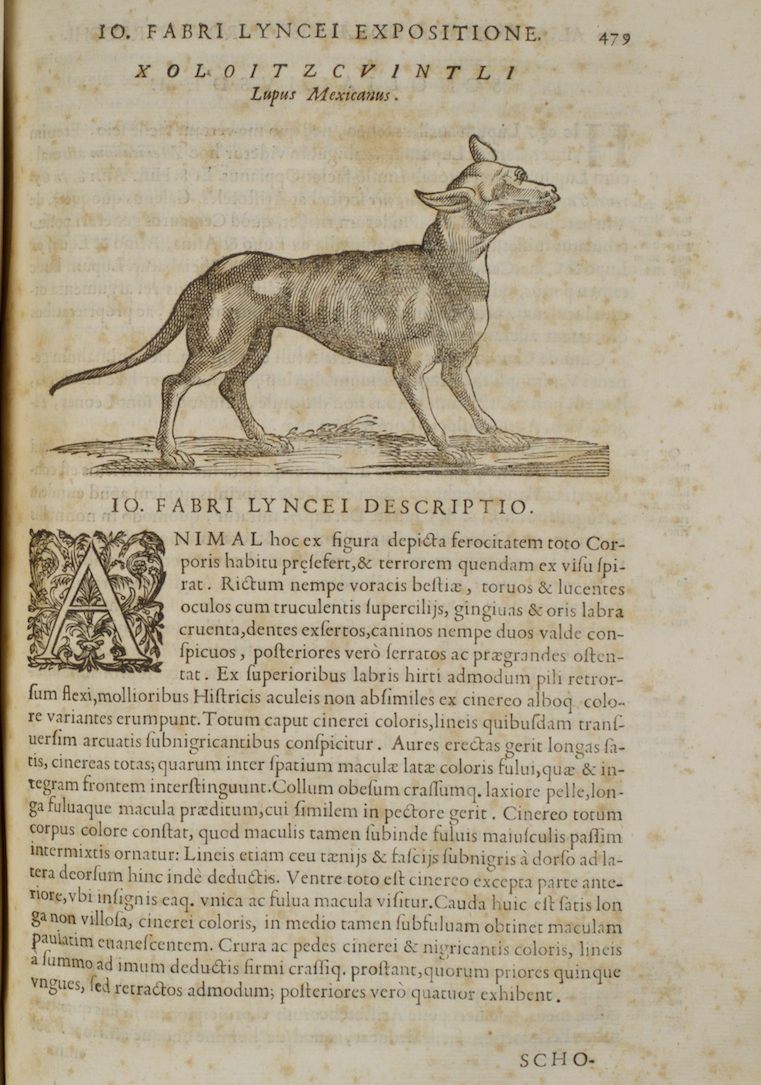

The xoloitzcvintli, or Mexican wolf.

The xoloitzcvintli, or Mexican wolf.

Enter Federico Cesi. The eldest son of a high-class Italian family, Cesi should have spent his life schmoozing with nobility and tending to family affairs. But Cesi had a thirst for knowledge, and he spent his early years learning everything he could about science. When he ran out of books, he went looking for more.

In 1603, 18-year-old Cesi took a trip to Naples, where he stumbled upon a cabinet of curiosities operated by an collector named Ferrante Imperato. Imperato owned some of the pages of Hernandez’s lost manuscripts, and Cesi found them fascinating. Here was the key, not just to a few more facts, but to a whole unknown world.

Enthralled by all the new creatures that were suddenly at his fingertips, Cesi made a vow: he would find all of Hernandez’s scattered papers, and publish a definitive edition, establishing the foundation of New World Natural History.

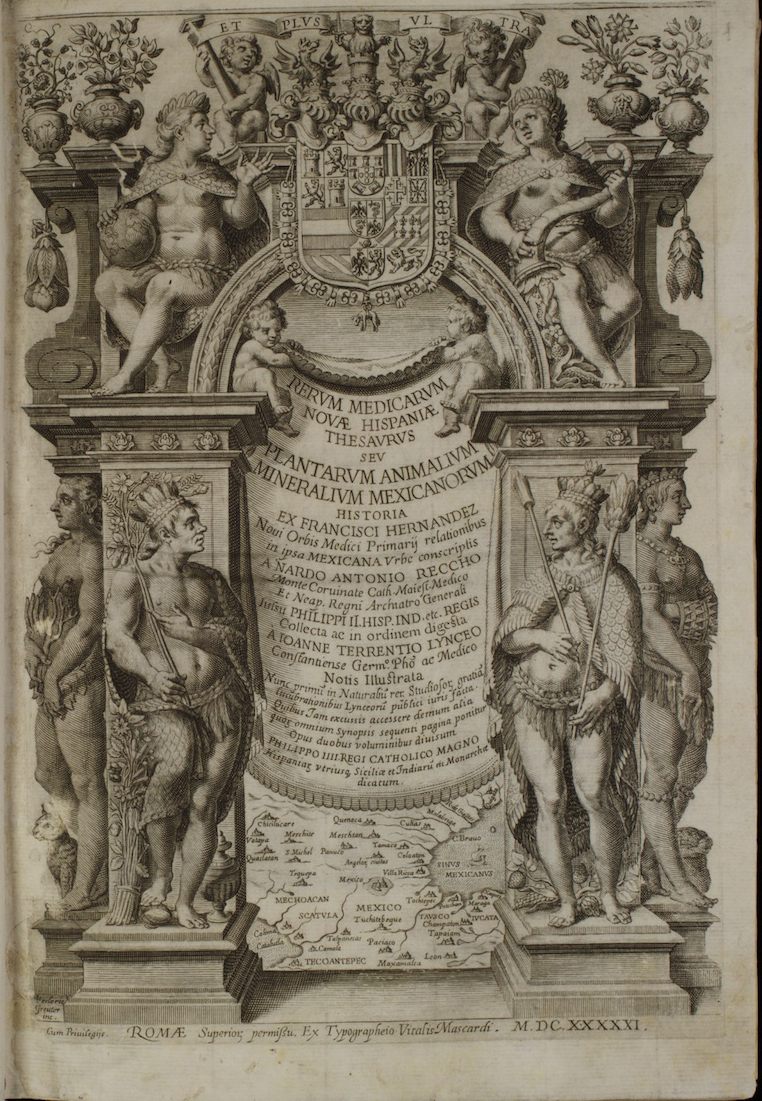

The intricate frontispiece, as befits a book that took 70 years to make.

The intricate frontispiece, as befits a book that took 70 years to make.

Cesi couldn’t do it alone—he needed a dream team, bright minds ready to tackle the many tasks required to turn far-flung, disorganized, and hard-to-understand pages into a reliable reference book.

So he founded something he called the Academy of the Lynx: “Lynx” because the cat was said to have the kind of penetrating eyesight that helps with mystery-solving, and “Academy” because this was an exclusive society, open only to the smartest of the smart (which turned out to mean mostly people Cesi was friends with, or admired).

It was selective enough that in 1612, nine years into the Academy’s existence, it still only had nine members—Cesi, his three childhood tutors, a few assorted Renaissance men, and an up-and-comer named Galileo.

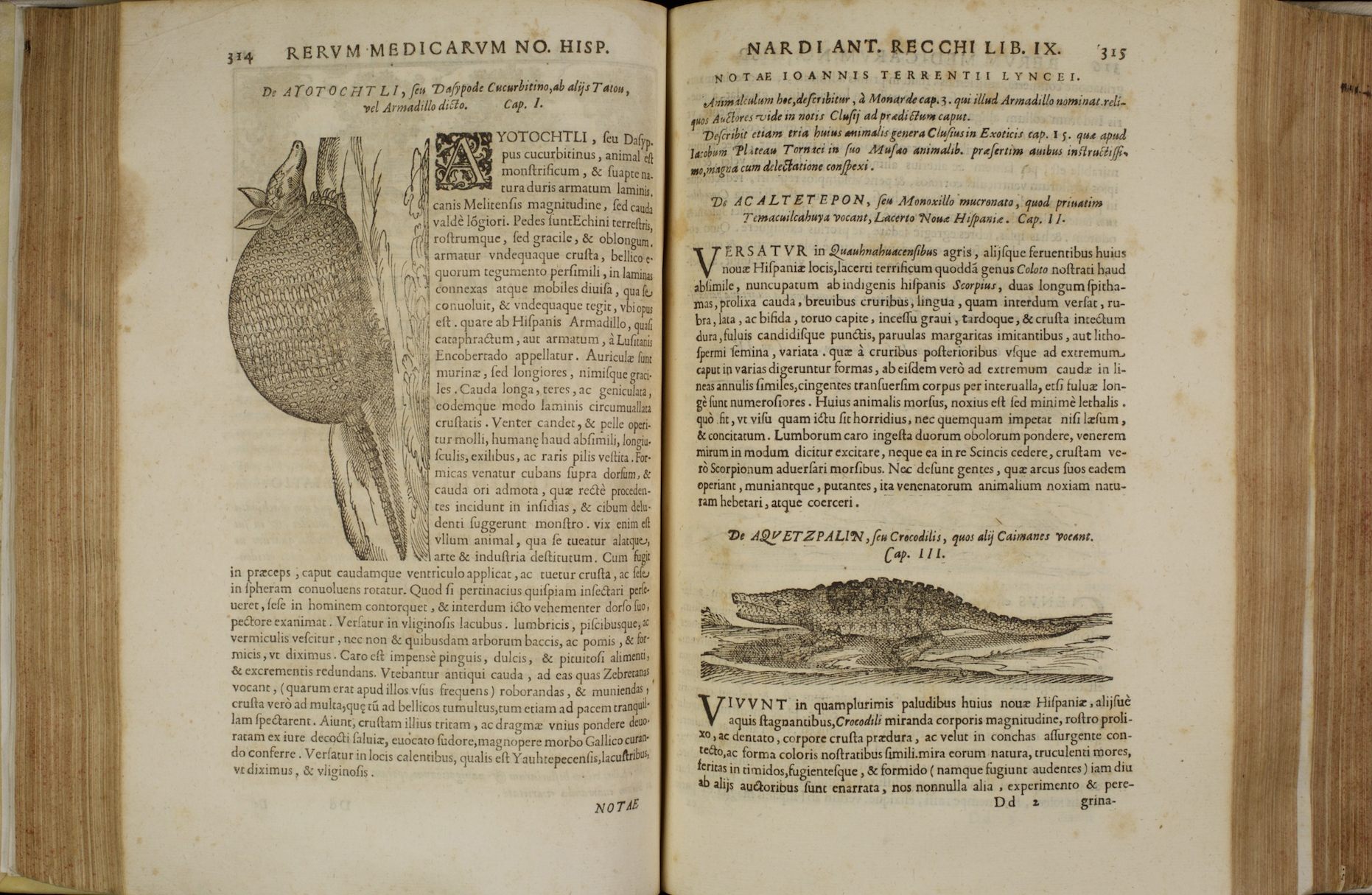

The armadillo and the crocodile. Hernandez and other experts believed in things like dragons, despite never encountering them, largely because the animals they did discover were so surprising.

The armadillo and the crocodile. Hernandez and other experts believed in things like dragons, despite never encountering them, largely because the animals they did discover were so surprising.

Cesi started spreading the word about his project, and naturalists across the continent began eagerly awaiting this “definitive edition,” which promised to swell their collections and clear up some botanical mysteries. Meanwhile, the Academy got to work, each member playing to his strengths. Cesi dedicated some of his considerable funds to buying up manuscript bits from various collectors.

Johann Schreck, a multilingual doctor, edited the flora section, which was heavy on medicinal plants. Johann Faber, an artistically talented anatomist, took care of the fauna. And the group worked together to produce 800 woodcut illustrations, to help Europeans better visualize all the strange new creatures that Hernandez described.

The Lynxes had many successes. They published members’ works, including Galileo’s The Assayer, and they worked hard to foster scientific discourse. At the height of their powers, they had 32 members from across the continent.

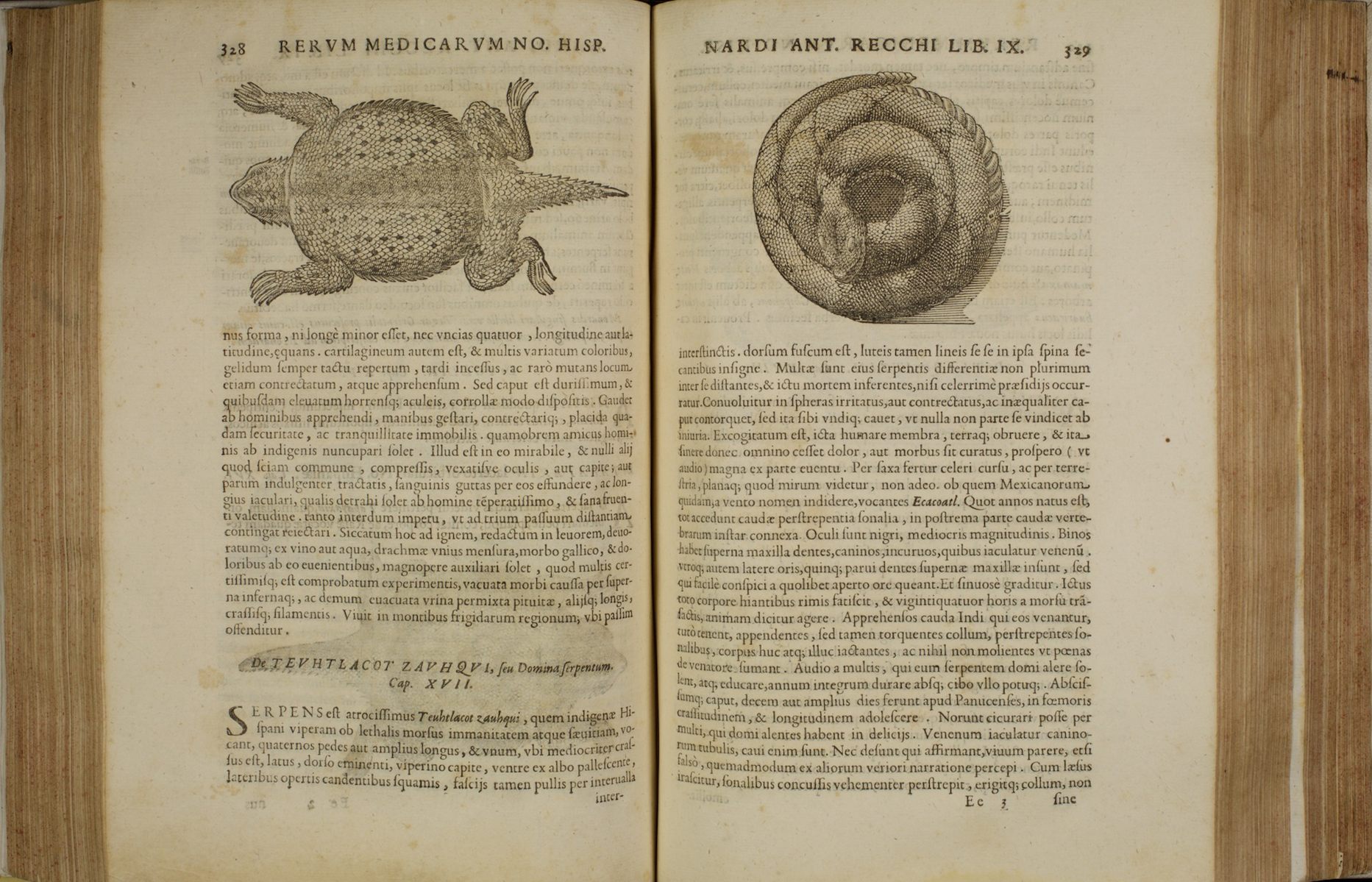

A couple of unprecedented reptiles.

A couple of unprecedented reptiles.

But it was hard and slow going. Cesi’s father tried to break the gang apart, accusing them of distracting his son from his familial responsibilities. As religious institutions grew suspicious of scientific practice, the climate for Academies like this soured. Galileo kept getting arrested by the Inquisition, and the Lynxes kept dropping everything to defend him.

By the time the book was finally put together, every member of what was once the Academy of Lynx was dead, save for one—Francesco Stelluti, one of Cesi’s former tutors (and the first person to ever publish observations taken through a microscope). Stelluti shepherded the project through to the finish line, and in 1651—seventy years after Hernandez’s return, and nearly half a century after Cesi took up the mantle—the definitive edition was finally published.

Its publication, the University of Oklahoma exhibitors write, “symbolized the transformation of natural history into a global endeavor.” It also gained Hernandez a reputation as “the Pliny of the New World.” Scientists relied on Hernandez’s observations, and the Academy’s presentation of them, into the 18th century. The book even earned a mention in a poem by Erasmus Darwin, Charles’s grandfather.

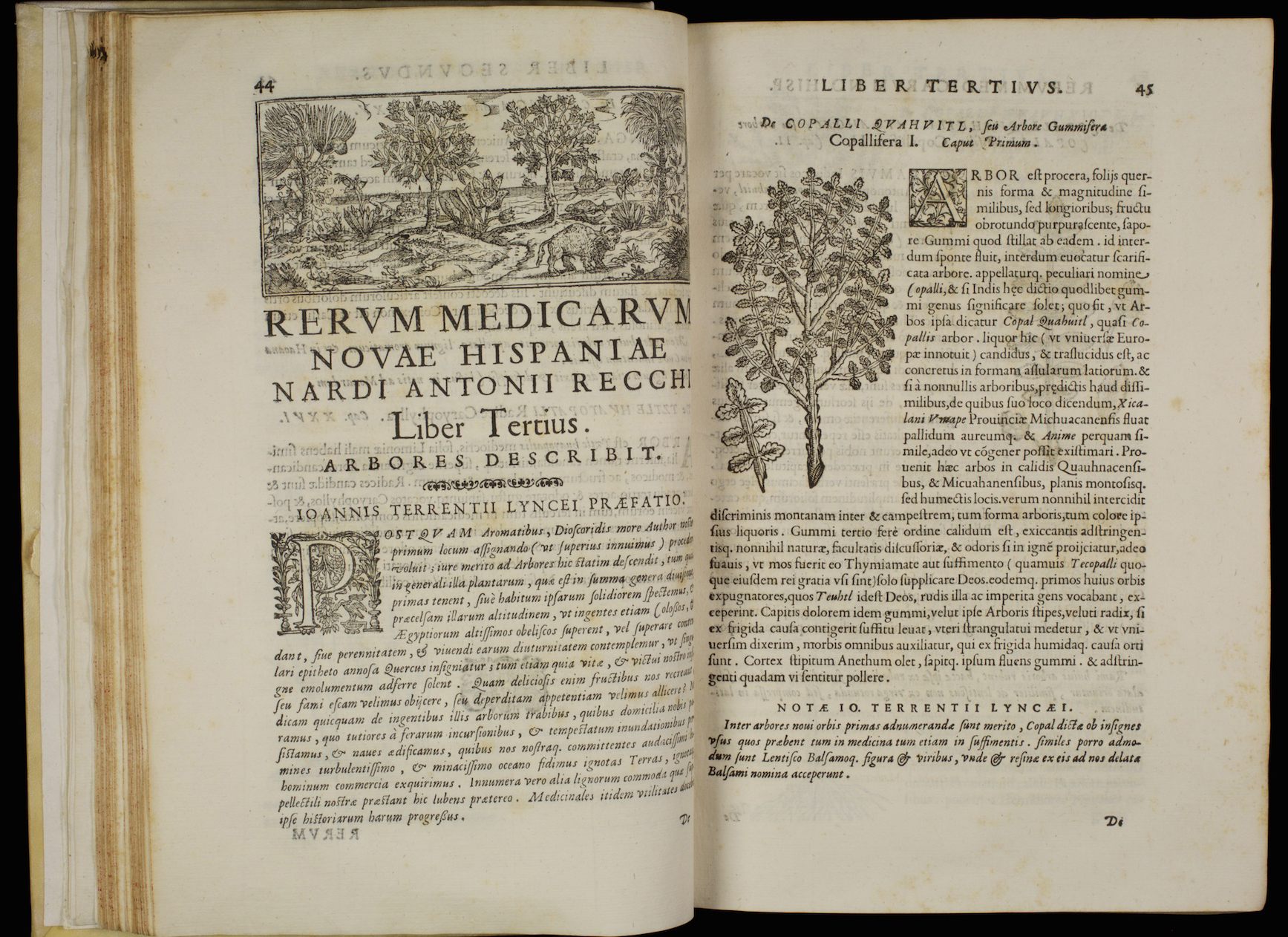

The beginning of the arboreal section, complete with a tree-studded scene

The beginning of the arboreal section, complete with a tree-studded scene

The University of Oklahoma curators hope that highlighting this book will help return Hernandez and his champions to their rightful place in the naturalist pantheon. Hernandez’s contributions, and his respect for indigenous knowledge, “show there was more to Spanish influence in the Americas than raw material exploitation,” says James Burnes, an organizer of the exhibit. A book like the Novum has “broad geographical and chronological impacts.”

As it jumps oceans and centuries, the knowledge it offers may change, but it does not diminish. Any lynx can see that.

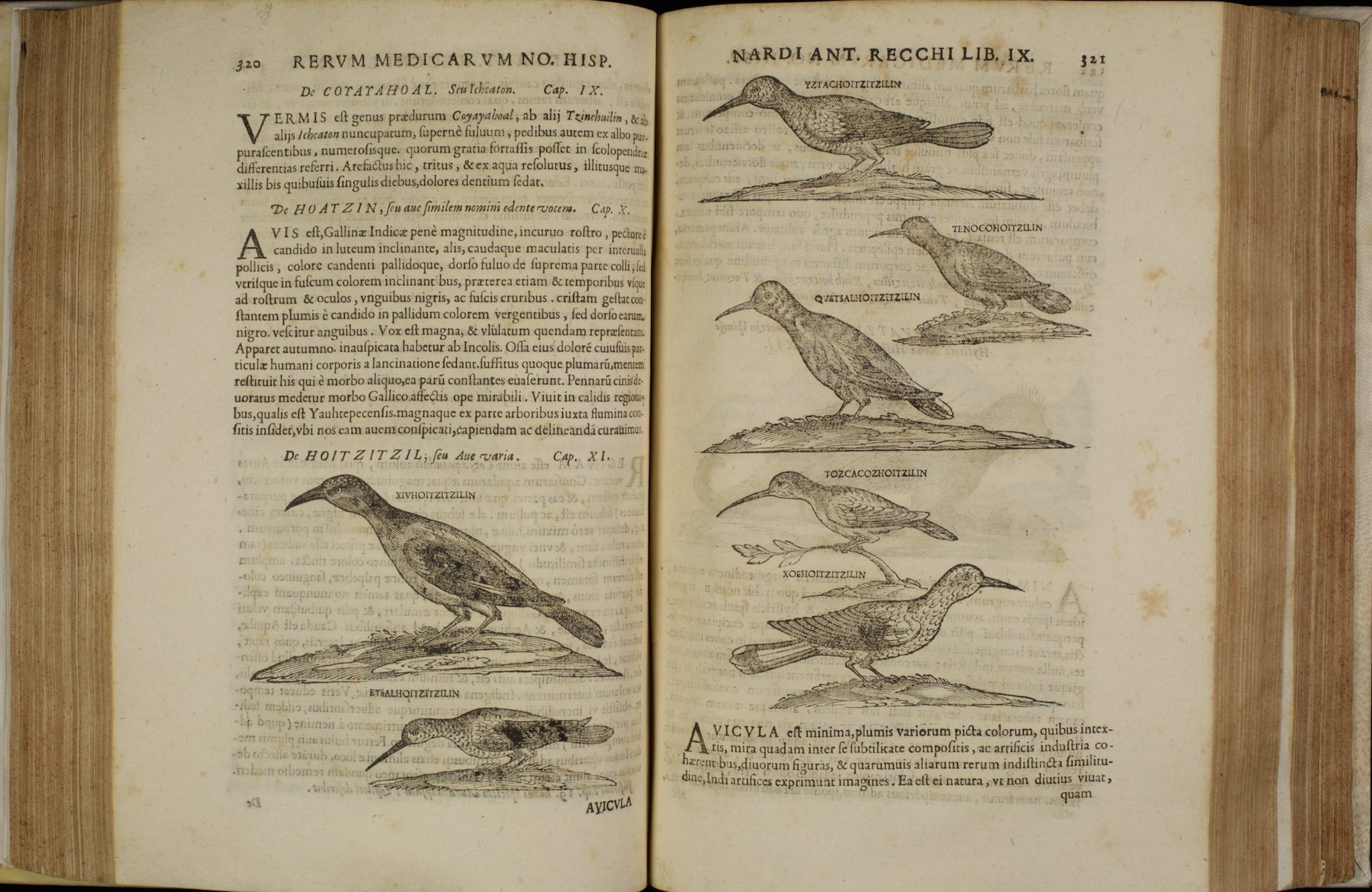

A flock of New World birds.

A flock of New World birds.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook