How to Win a 19th Century Election

The Tamany Hall Ballroom decorated for the National Convention on July 4th, 1868. (Photo: NYPL Digital Gallery/ Public Domain)

Today’s long and loud election season may be exasperating, but it doesn’t hold a candle to the corrupt, fraudulent and violent elections of 19th century America. Nothing was off limits when making sure that the “right candidate” was elected to office.

Bribery wasn’t simply a common occurrence, it was expected. Political machines–most famously, New York’s Tammany Hall–reigned supreme. All-out brawls were a common sight at the polling stations.

For many, though, it wasn’t simply a matter of making sure the candidate who got elected agreed with your political leanings. It was more about making sure the people who were in office would protect you and your family. People voted to ensure their survival. Candidates, for better or worse, used this mentality to their advantage.

The story of how “Honest John” Kelly won the 1853 election was a common one in 19th-century politics. As a proud Irishman and practicing Catholic, Kelly knew something had to be done. The Know-Nothings had taken control of Kelly’s beloved Fourteenth Ward through intimidation, violence and voter fraud. Kelly couldn’t take the Know-Nothings’ anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic regime any longer.

He had run for office and lost twice before due to his supporters being scared off while attempting to vote. But this time, it was going to go differently–Kelly was determined to win. Known throughout the neighborhood as “Honest John” (though some would call him this ironically later), Kelly didn’t want to stoop to the level of the opposition. But he knew it was necessary.

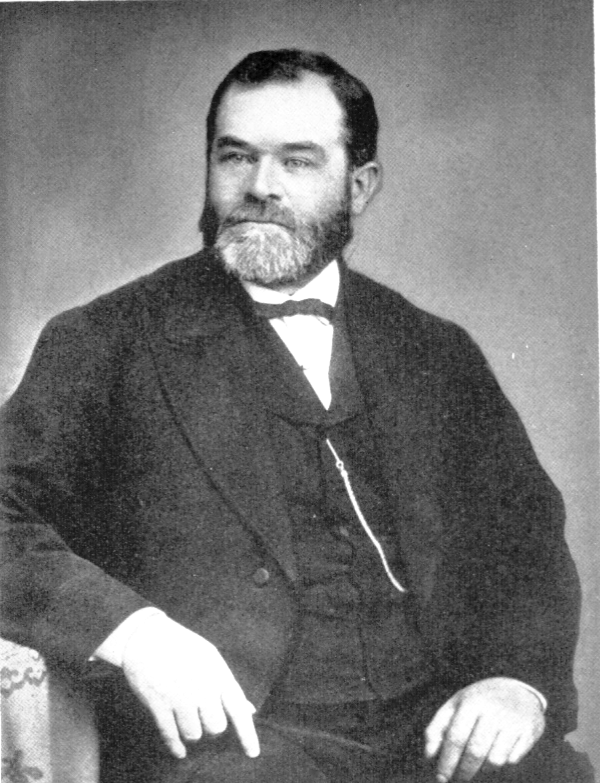

John Kelly, c.1880 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

John Kelly, c.1880 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

On Election Day of 1853, Kelly and his men marched to the Fourteenth Ward’s polling place at the corner of Elizabeth and Grand Streets. Firemen, shipyard workers and the local Irish gang, all of whom were looking for a fight, joined him. Upon entering the polling location, they smashed tables “into splinters” and ripped apart ballots that didn’t have “Kelly” written on them. They menacingly told those who were voting for the Know-Nothing candidate to reconsider their choice.

Within minutes, the Know-Nothings reinforcements showed up and an all-out battle ensued. Fists were thrown, buildings were set ablaze and ballots were ripped to shreds. When the dust finally settled, John Kelly and his Irish-Catholic cronies had won the skirmish and the election against the Know-Nothings. Though order was restored, this wasn’t exactly the democracy that America’s founding fathers had envisioned.

From engaging in “cooping” to questioning an opponent’s gender, below are some of the wiliest tried-and-true methods for winning a 19th century election.

Prey on the Desperation and Fears of the People

From 1815 to 1915, over 30 million people arrived to the America’s shores from Europe. The immigrants came to the country in the hopes of finding a better life. Met with overcrowded tenements, insufferable working conditions and xenophobia, their high expectations were often not met. Desperate for simple necessities like coal, food and medical care, political machines would often offer these things to immigrants in exchange for their loyalty and partisanship.

Jobs were also scarce, and politicians found that densely packed slum neighborhoods were a perfect place to find desperate people ready to do their dirty work. State Senator George Plunkitt, a member of Tammany Hall, once acidly observed, “the poor are the most grateful people in the world.”

Sometimes, this relationship was mutually beneficial. Tammany Hall leader and two-term New York City mayor Fernando Wood would send his cronies to the docks to wait for the ships from Europe to pull in. As people climbed off the boats, the cronies would offer them a chance to immediately become naturalized American citizens. The ones that took the opportunity become Tammany Hall voters for life.

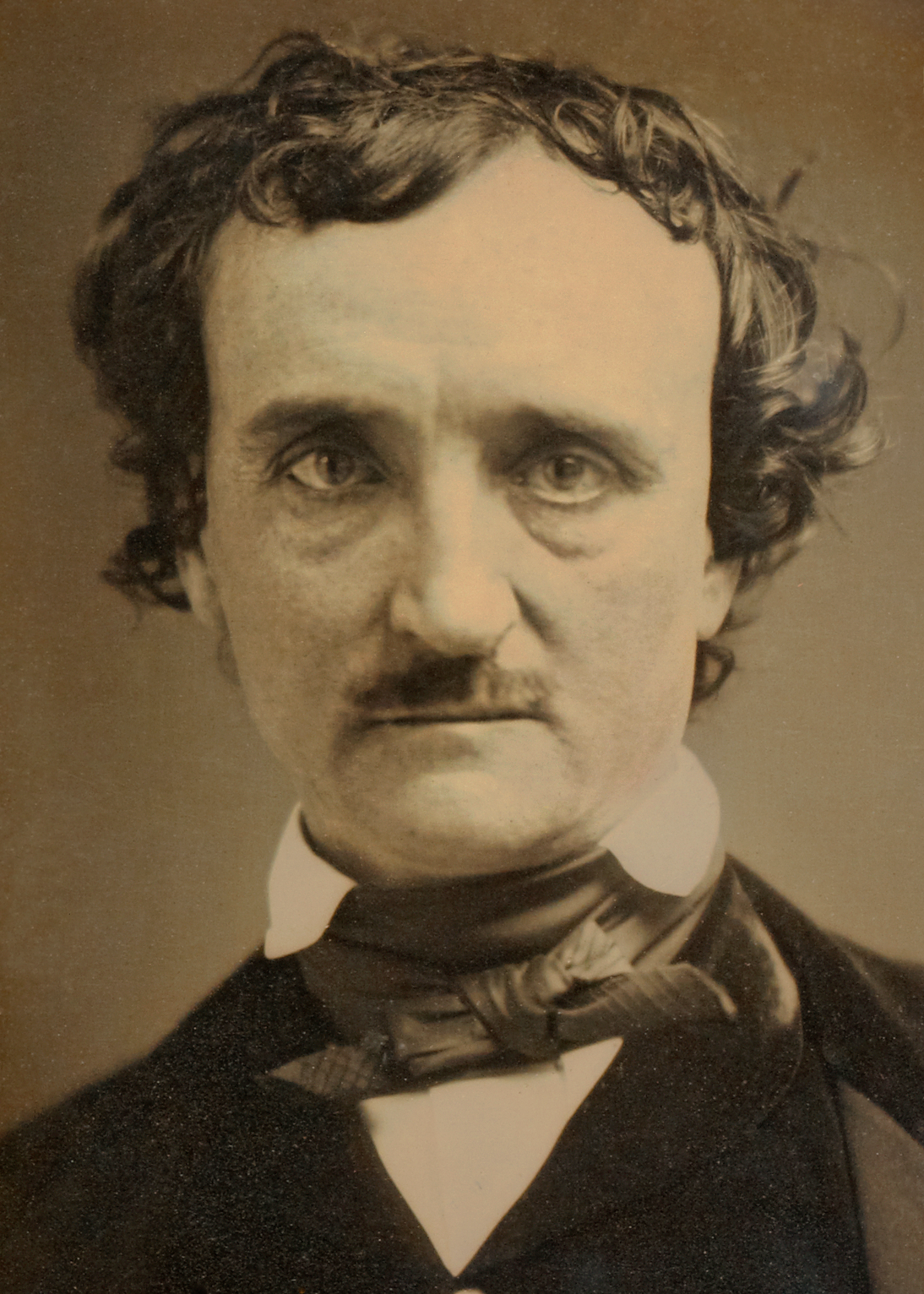

Edgar Allen Poe, 1849 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Edgar Allen Poe, 1849 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Turn Drunks into Voters

Much like today, voter turnout was important to candidates vying for 19th century office. Instead of incessant robo-calls, though, candidates and their campaigns frequently employed a strategy known as “cooping.” This practice involved roaming the streets late night and rounding up the drunk, drugged-up, homeless or otherwise incapacitated men they found.

Campaign workers would lure the men into a basement or backroom using food and alcohol and trapping them there–much like “chickens in a coop.” On Election Day, they were force-fed alcohol and dragged to polling place after polling place, making sure they voted for the “correct candidate.”

While there were certainly rules against voting multiple times, they were hardly enforced due to the lack of records and preponderance of bribes. Additionally, the men were often obligated to wear many different outfits, hoping that a change of clothes would allow them to go unnoticed.

It has long been rumored that Edgar Allan Poe was a victim of cooping. On Election Day, 1849 in Baltimore, Poe was found near a polling place, lying in gutter, delirious and wearing soiled clothes. He was admitted to the hospital, but never again became coherent enough to explain what had happened to him. He died several days later during a fit of visual hallucinations.

A glass globe ballot jar circa 1884. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A glass globe ballot jar circa 1884. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Make Ballots Color-Coded and Ballot Boxes Glass

It wasn’t until 1891 that every state in America moved to a fully secret ballot, known as an “Australian ballot.” Prior to that, the individual political parties distributed ballots and were able to design them as they pleased. Often times, the parties would color-code or put distinctive designs on their ballots as a means to not only attract voters, but also make it quite apparent to all which party and candidate the voter was voting for. For example, if a voter was thinking about voting Republican in an overwhelming Democratic district, that voter may want to think twice with all of those Democratic eyes on him.

While glass ballot boxes became a symbol of democracy at work during the 19th century, they also allowed campaign officials to see each individual vote as it was cast.

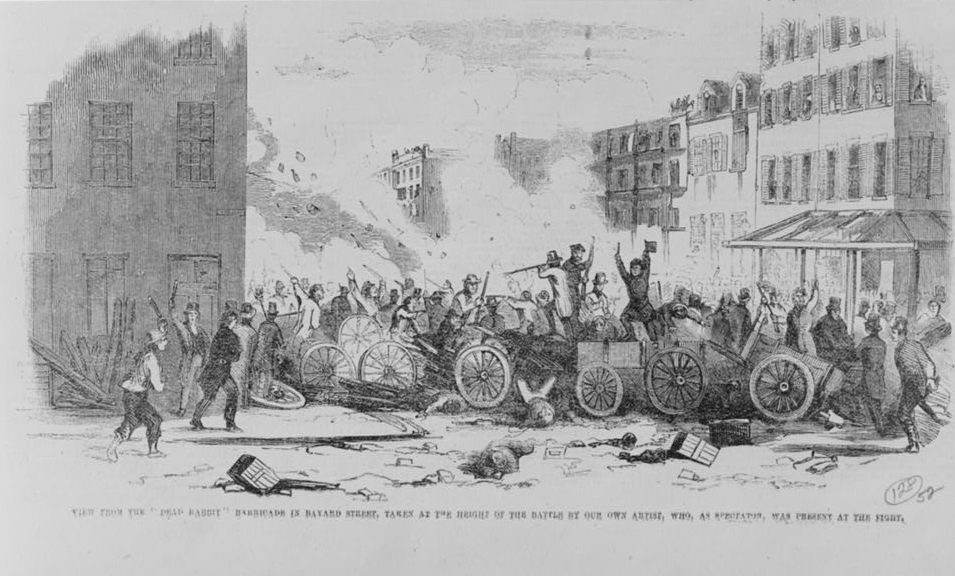

1857 View from the “Dead Rabbit” barricade in Bayard Street, taken at the height of the battle by our own artist, who, as spectator, was present at the fight. (Photo: Library of Congress)

1857 View from the “Dead Rabbit” barricade in Bayard Street, taken at the height of the battle by our own artist, who, as spectator, was present at the fight. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Align with Street Gangs and Start Riots

As exemplified by John Kelly and the Know-Nothings, Election Day violence and riots occurred throughout the 1800s. More often than not, urban street gangs played a significant role. While the movie Gang of New York popularized the creatively named New York street gangs–for example, the Dead Rabbits, the Forty Thieves, Whyos–other cities had their share of violent groups as well.

Baltimore had the Plug Uglies and the Rip Raps, who began the Election Day riots of 1855 and 1856. The Flayers from Philadelphia were known for starting racially motivated riots on Election Day in an effort to scare off voters.

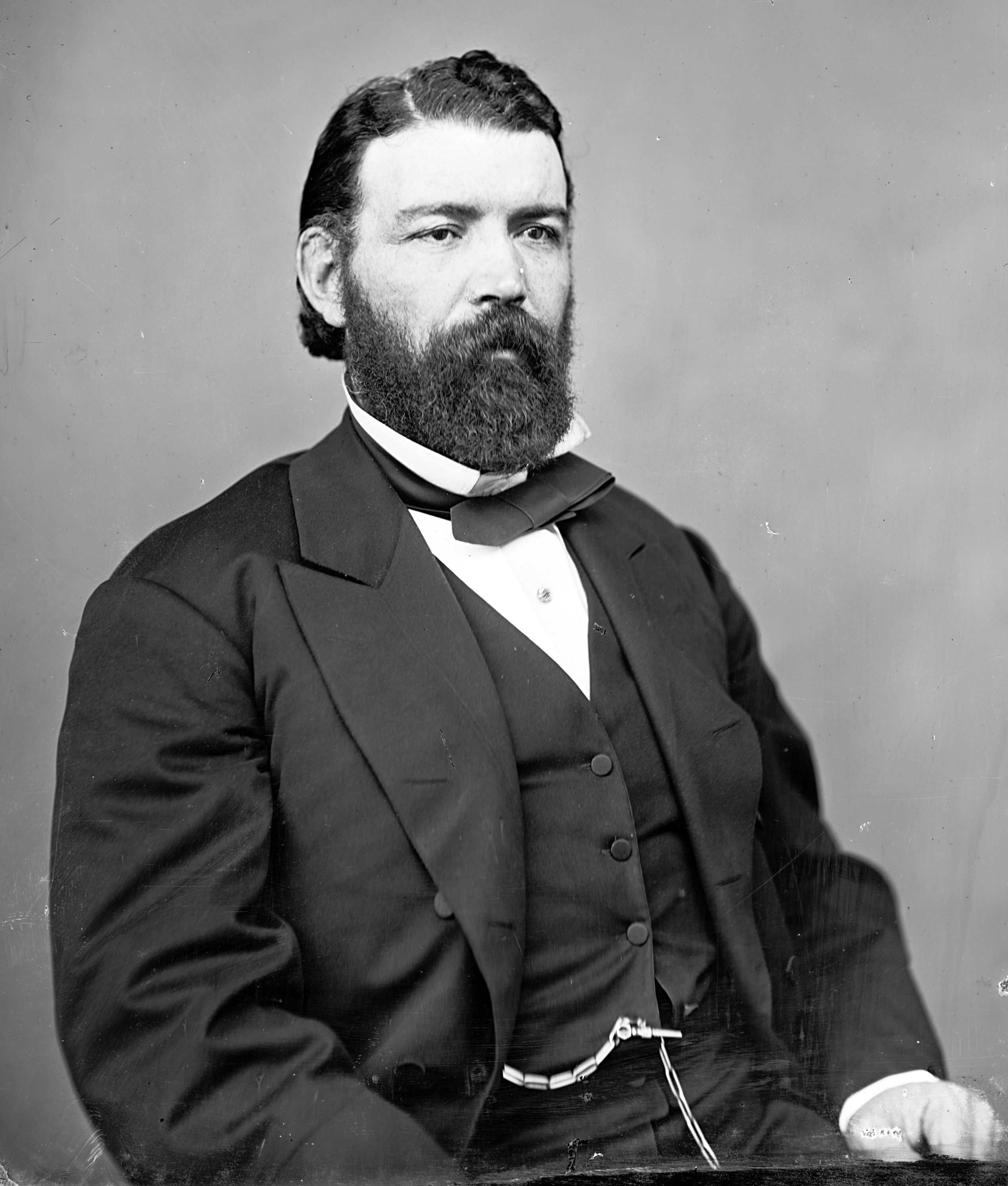

Sometimes it was also about who had the most muscle. Political parties would hire well-known amateur boxers and bare-knuckle fighters to stand guard at the ballot boxes, intimidating with a mere crack of the wrist. Sometimes, these fighters would become politicians themselves. There are many tales of John Morrissey and Bill “The Butcher” Poole using their fighting skills to intimidate those who would dare to step into the political ring with them.

John Morrissey of NY. (Photo: Library of Congress)

John Morrissey of NY. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Pay for Votes with Sandwiches

While it should be no surprise that voters sold their votes routinely in the 19th century, the price could also be discounted. “Floaters” would offer up their vote to the highest bidder, but sometimes it didn’t take much–maybe a few bucks and a sandwich.

One source documents that during an 1896 election in Indiana, 30,000 floaters offered up their vote for liquor, a sandwich and five dollars. While several historians believe that the impact floaters had on election results are greatly exaggerated, there was a 1911 case in Ohio where a local judge tried and convicted over a quarter of the voting electorate for selling their votes.

Even if “floaters” were limited to a relatively small select group of people, it could still have a great national impact, as it may have had on the 1888 Presidential election between Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison. A rash of last-second vote-buying in Indiana may have turned the election in favor of Harrison.

Call the Opponent Mentally Deranged and Question Their Gender

The election of 1800 turned two former allies, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, into competitor. Having worked together drafting the Declaration of Independence, the men had mutual admiration for one another. But that all deteriorated in 1800, with each fiercely believing the other would ruin the newly formed country if elected President.

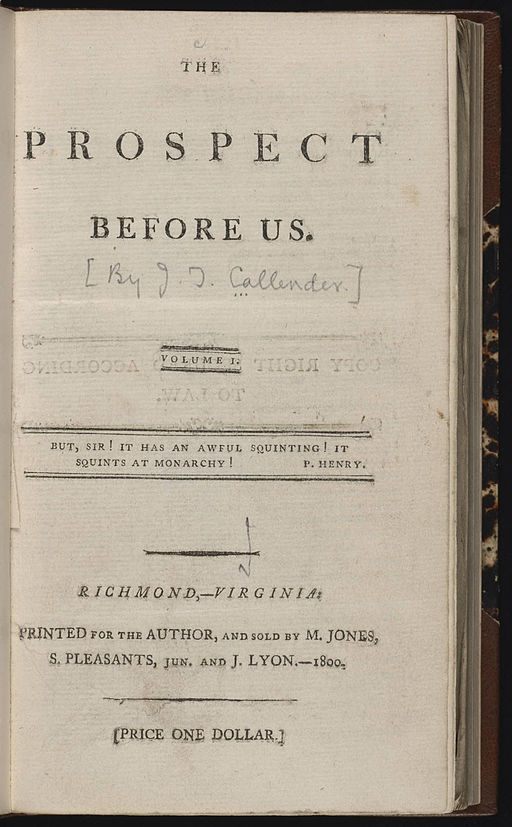

While both men would eventually take shots at one another, it was Jefferson who shot first. Newspaper writer James T. Callender was already known to the political elite for his written revelations that Alexander Hamilton was having an affair with a married woman. This greatly impressed Jefferson, for he was not fan of Hamilton either. So, Jefferson secured Callender’s services and secretly paid him to write “The Prospect Before Us,” a pamphlet directing charges that the “mentally deranged” Adams wanted to turn America into a royal monarchy.

Title page of “The Prospect Before Us,” the anti-Federalist tract by political pamphleteer and journalist James T. Callender. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Title page of “The Prospect Before Us,” the anti-Federalist tract by political pamphleteer and journalist James T. Callender. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Callendar didn’t stop there though, calling Adams a “hideous hermaphroditical character.” Upon reading an early draft of the pamphlet, Jefferson wrote Callender that it “cannot fail to produce the best effect.”

Needless to say, this rumormongering did not sit well with many, including the United States government. Callender was actually arrested under the Sedition Act and was jailed for nine months in Richmond. Meanwhile, Thomas Jefferson was elected President, thanks in no small part to Callender’s efforts.

Callender would have his revenge, though. While Jefferson did give Callendar a reprieve in the form of a Presidential pardon, the writer felt he was owed more–namely, money and a cushy postmaster appointment. Jefferson refused the postmaster request, but back-channeled Callender more money–an extra fifty bucks, which in today’s money is less than thousand dollars.

A year later, Callender would publish his next pamphlet, “The President Again,” a severe takedown of Jefferson in which he revealed the secret relationship between the President and Sally Hemings, a slave at his Monticello estate.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook