The Italian Immigrants Who Grew Fig Trees in Unlikely Places

A grassroots group is creating a living library of these backyard gardens.

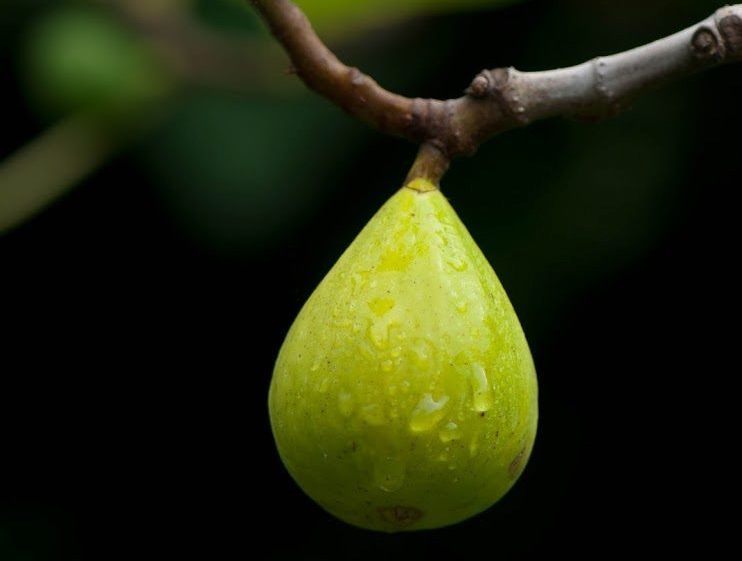

They brought them in suitcases and in trunks, tucked into the corners of boats and, later, on airplanes. Seeds that became rapini, cardoons, artichokes, cucuzza squash. Cuttings from knobby grape vines that flourished into backyard arbors. And, above all, bits of stick that grew into fig trees. Starting in the late 1800s, when Italian immigrants poured into U.S. port cities, the Mediterranean trees took root in unexpected places: Astoria, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Bayonne, cities whose cold-weather climates seemed hostile to the plant. Yet the trees grew, even if their owners had to wrap them in burlap or bury them underground so they’d survive the cold winters.

You can still identify historically Italian neighborhoods by the presence of backyard fig trees. “I’ve literally walked around Brooklyn looking in backyards, and I can tell,” says Mary Menniti. “Oh, there’s a fig tree in the backyard and a Madonna. That’s an Italian-American garden.”

The granddaughter of Italian immigrants, Menniti is documenting these fig trees through the Italian Gardens Project, a living archive of Italian-American gardens and their keepers. Since 2009, she has profiled Italian-American gardeners around the country, documenting the objects that make the gardens distinct: old-fashioned gardening tools; the icons of Roman Catholic Saints; braids of garlic hanging from garage ceilings. Recently, Menniti focused her attention on fig trees. She’s collecting heirloom fig trees from Italian-American gardeners, and plans to build a fig-tree garden that will serve as a living museum to their regional diversity.

The project has deep roots. Menniti grew up with the yearly ritual of caring for fig trees in an Italian neighborhood outside of Pittsburgh that was filled with sprawling vegetable gardens. Her paternal grandfather, who immigrated from Campania and never quite learned English, would come home after long days at the steel mill and work in his garden. Fruit was a language he knew. “When he was in the garden, he felt the most comfortable,” Menniti says.

Menniti’s grandfather was part of a generation of turn-of-the-century Italians who immigrated mostly from agricultural Southern Italy to American cities. In the early 1900s, Southern Italian dishes such as pizza and vegetables like cardoons were rare in public life and often looked-down-upon. Italian Americans grew kitchen gardens as a means of survival, and a way of accessing Mediterranean produce. The tradition persisted with later generations of immigrants. Michele Vaccaro, who immigrated from Calabria to Pittsburgh in the 1970s, says gardening connects him to his roots. “When we come from Italy, we bring Italy with us,” he says. “We never forget where we come from.”

As a young person, Menniti says, she took gardening for granted. But with the rise of supermarkets and increased assimilation, the tradition faded among her parents’ generation. When she moved to a neighborhood filled with more recent Italian immigrants as an adult, a longing for gardens struck Menniti like a falling fig. As she interacted with her new neighbors, including Vaccaro, she realized that unless she did something about it, their knowledge could be lost. “I really said, ‘Wait, they’re not going to be here forever either,’” she says. “Let’s learn from them.”

For the past 10 years, Menniti has travelled the country to document these gardens, and has shared the gardens in her own neighborhood through a walking tour and classes with home chefs. She receives stories, photographs, and seeds from Italian-American gardeners. The gardens she photographs are filled with Mediterranean heirlooms, many of them smuggled in suitcases generations ago: Sicilian saucer tomatoes, dozens of varieties of chicoria, sour broccoli rabe.

Of all the plants Menniti profiles, none has the pull of the fig tree. “I’ve never seen one plant that evokes so much emotion,” she says. Sometimes, she sets up a booth at Italian-American festivals with a small fig tree in tow. “I could have a stack of gold bullion and it wouldn’t attract as much attention,” she says. “People come up and have this look about them—they want to share that story.”

Menniti says this love of fig trees comes from reverence for a historical means of survival. For agricultural people in Southern Italy, a fig tree offered a source of fruit that could be dried and kept for lean times. The trees also became a symbol of adaptation. “I can get this to grow where it’s not supposed to grow. It adapts and thrives in a land not its own,” Menniti says of her grandparents’ mindset. “I can thrive here if this tree can make it.”

When project participant Nick Ranieri immigrated to Flushing, Queens from Mola di Bari, Puglia, in the 1960s, his first thought was of fruit trees. He was surprised to see that some neighbors had persimmon trees. He ordered his own from a catalogue. But the American fruits were no good. “It was kind of wild—very small and bitter,” he says. So he went straight to the source. “I thought, ‘Okay, some of my paesan, they have a tree they brought from Italy,’” he says. He took stems and grafted them onto his American tree; they grew good fruit. Figs were next: He brought back cuttings of two varieties of fig trees from his neighborhood in Italy, and planted them in his American backyard. “Yes, they all came in a suitcase,” he laughs.

Now retired and living in Long Island, Ranieri is locally renowned for growing unexpected Mediterranean and Middle-Eastern plants, including, at one time, apricots, almonds, lemons, and chestnuts. “I had artichoke plants and people didn’t even know what they were,” Ranieri says. When he told neighbors it was an artichoke, they were incredulous. “Artichoke plant? ‘It’s a plant that grows in California, not here.’” Ranieri’s voice fills with pride. “Well, I grew it here.”

Winterizing these plants is a yearly ritual. Ranieri builds a plastic tunnel to protect the artichokes, which are perennials. He covers his fig trees with a layer of insulation to protect them from the cold: first tying the lithe branches with electrical wire, then wrapping the tree with a layer of roof paper and a layer of canvas before stuffing the package with leaves. An upturned bucket crowns the tree to keep the insulation dry for the winter.

To protect young trees, some gardeners actually bury them underground. Vaccaro has several fig trees; his favorite comes from cuttings he took from his family farm in Italy and has fruit “like honey.” He learned to bury the young trees from his ex-father-in-law, and recently taught Menniti, whom he’s related to through a chain of in-laws and cousins back in Italy.

Young fig trees, those less than about six inches in diameter, are resilient; they can bend without breaking. Vaccaro digs a trench, cuts some of the roots to partially unhinge the tree, then pushes the trees into the trench. (Last year he hitched the trees to his truck to bend the saplings.) The saplings are suspended by their roots in the trench all winter, insulated with leaves and plywood, and bounce back when cut free in spring. While there is a risk of the trees freezing to death over the winter if not properly insulated, even frozen trees almost always grow back from the root. “The branches, they die,” says Vaccaro. “The trunk never dies. So now, here, you start again.”

For Menniti, archiving knowledge about these trees is a reminder of the resilience of their growers. Menniti has documented several Italian-American gardens for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Gardens collection. She throws a yearly fig festival in her home town in Pennsylvania. And she’s building a physical collection of Italian-American heirloom seeds and cuttings, including fig trees, which she sends to gardeners around the country as part of a growing seed exchange. Menniti plans to build a garden of heirloom fig trees open to the public, accompanied by an archive of oral histories from each family who contributes. She hopes to eventually include contributions from other communities that connect to the fig tree, including Greek Americans and Turkish Americans.

This year, Menniti has finally built up a large enough collection to share. As we speak for this article, she’s planning to mail a small fig tree she got from a Calabrese gardener to a man in Connecticut. “He said, ‘My family was from Calabria and I have no heirloom for that, no family treasure. I want to grow that tree,’” Menniti says.

My own ancestors immigrated from Italy during the same generation as Menniti’s. My childhood bedtime stories were full of my mother’s recollections of their gardens, lush with misshapen carrots, heavy-laden grape arbors, and sweet, acidic vats of backyard tomato sauce. Ever since I can remember, my father has talked longingly of fig trees, part of a lifelong quest to finally grow one in our New Jersey backyard. When I interview Menniti, I’ve just received something special from my grandmother’s house: A cutting from her grape vine, grown from a cutting from her father’s. I don’t know if the vine came directly from Italy. I do know, as I sit watching it in a little yellow pot on my windowsill, that its rooting is tied to my own.

For Menniti, every harvest of her own fig tree is a similar elegy, an act of both remembrance and growth. She recalls her grandfather’s garden. “When I’m handling that fig tree or picking those trees, I’m close to him.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook