Joseph Smith’s Vermont Hometown Is Being Transformed Into a Modern Mormon Utopia

And the area residents are not thrilled.

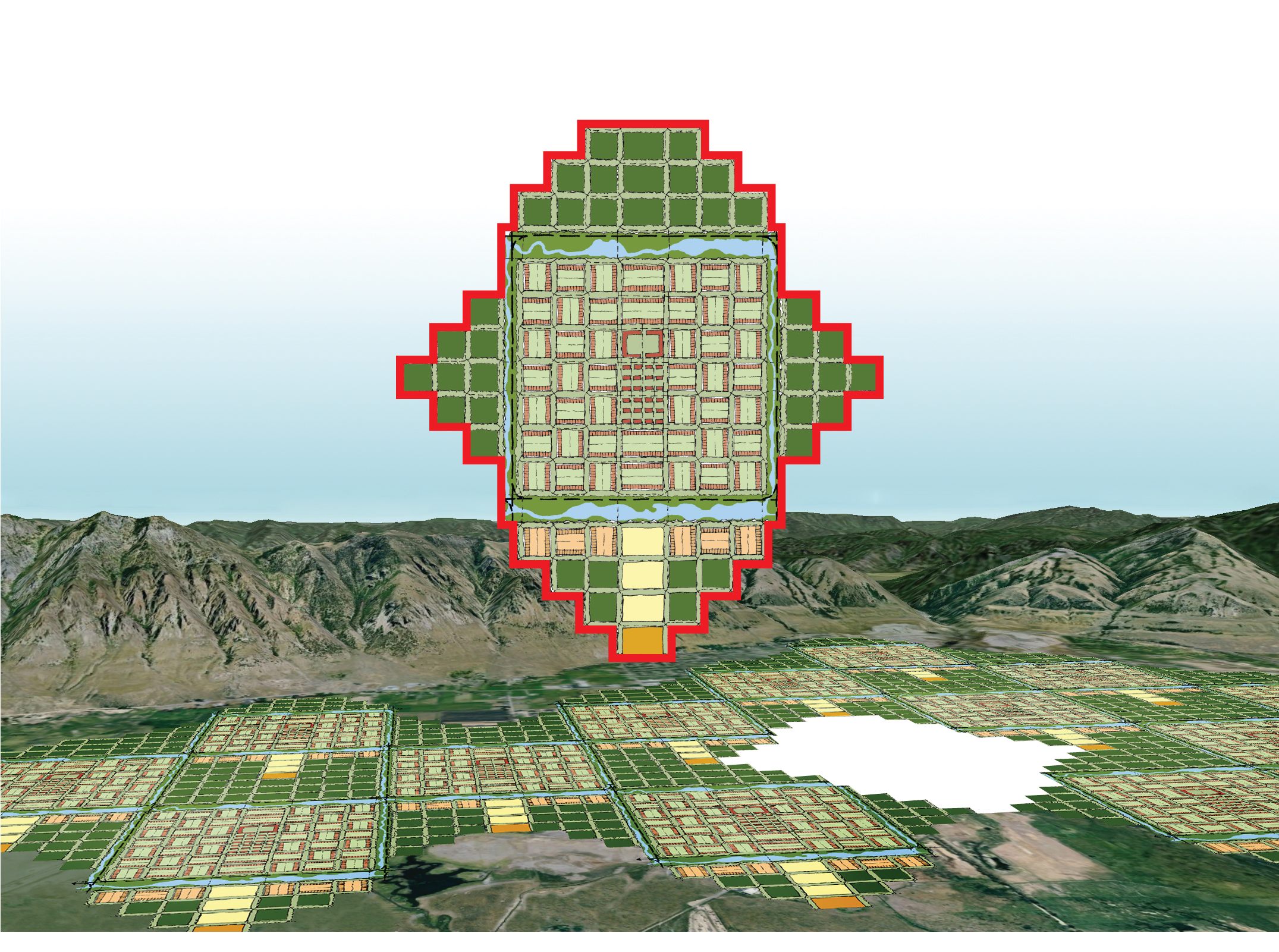

A view of the proposed community in Sharon, Vermont. (Photo: Courtesy The New Vistas Foundation)

About 140 miles northwest of Boston sits the tiny hamlet of Sharon, Vermont. Built along the banks of the White River, Sharon, with its white steeple church, rustic country store and American flags fluttering in the breeze, is a quintessentially New England town. But Sharon also happens to be the birthplace of Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Latter-day Saints, otherwise known as the Mormons.

Smith was born on the border of what are now Sharon and South Royalton; and in 1905 the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints erected a 50-foot tall granite obelisk in his honor. Despite the 80,000 tourists or so who make the pilgrimage, the communities surrounding Sharon and South Royalton remain sleepy towns among pastoral rolling green hills.

That may all change if David Hall’s dream comes to fruition. He wants to build a 21st century version of a utopic development—one with very tiny dwellings.

Joseph Smith birthplace obelisk. (Photo: Kimberly Vardeman/CC BY 2.0)

Hall, a millionaire former Mormon bishop from Provo, Utah, has been purchasing land in the two towns, plus Strafford and Tunbridge to the north, with plans to build a series of communities that will eventually house 20,000 people in an area of less than 3 square miles. Currently, the area has a combined population of roughly 4,500. He’s bought about 1,500 acres of farmland and houses, with a goal of securing a contiguous parcel of 5,000 acres.

“I think it will take 25 years to obtain that,” Hall says from his home in Utah. “I’m not just buying anywhere, but a specific spot, [centered around Smith’s birthplace] and you have to wait for people to be ready.”

Hall is just the latest futurist to try to impose a prescribed community on Vermont. During the 19th century, the Green Mountain state was home to a number of utopian societies, most of them religious in nature. The most notorious was the Oneida community, founded in 1841 by John Humphrey Noyes, of Putney. Also called Perfectionists, members practiced free love (referred to as “complex marriage”) more than a century before the term was coined, and believed that Christ had returned to earth in AD 70. Facing growing hostility from the locals, the Perfectionists moved to Oneida, New York in 1847.

The proposed community layout, consisting of 50 diamond-shaped settlements. (Photo: Courtesy The New Vistas Foundation)

Then there was the group in Hardwick that barked like dogs, and the members of a society in Woodstock that dressed themselves in animal skins and refused to bathe.

“You can imagine how well that went over,” says Jackie Calder, curator at the Vermont Historical Society.

The back-to-the-land movements often associated with Vermont in the 1960s and ‘70s actually got their start in the ‘30s, when Scott Nearing, a communist social activist, and Helen Knothe moved to Winhall. The couple advocated self-reliance and utilitarianism, and in 1954 Nearing and Knothe (who were married in 1947) co-authored Living the Good Life: How to Live Simply and Sanely in a Troubled World.

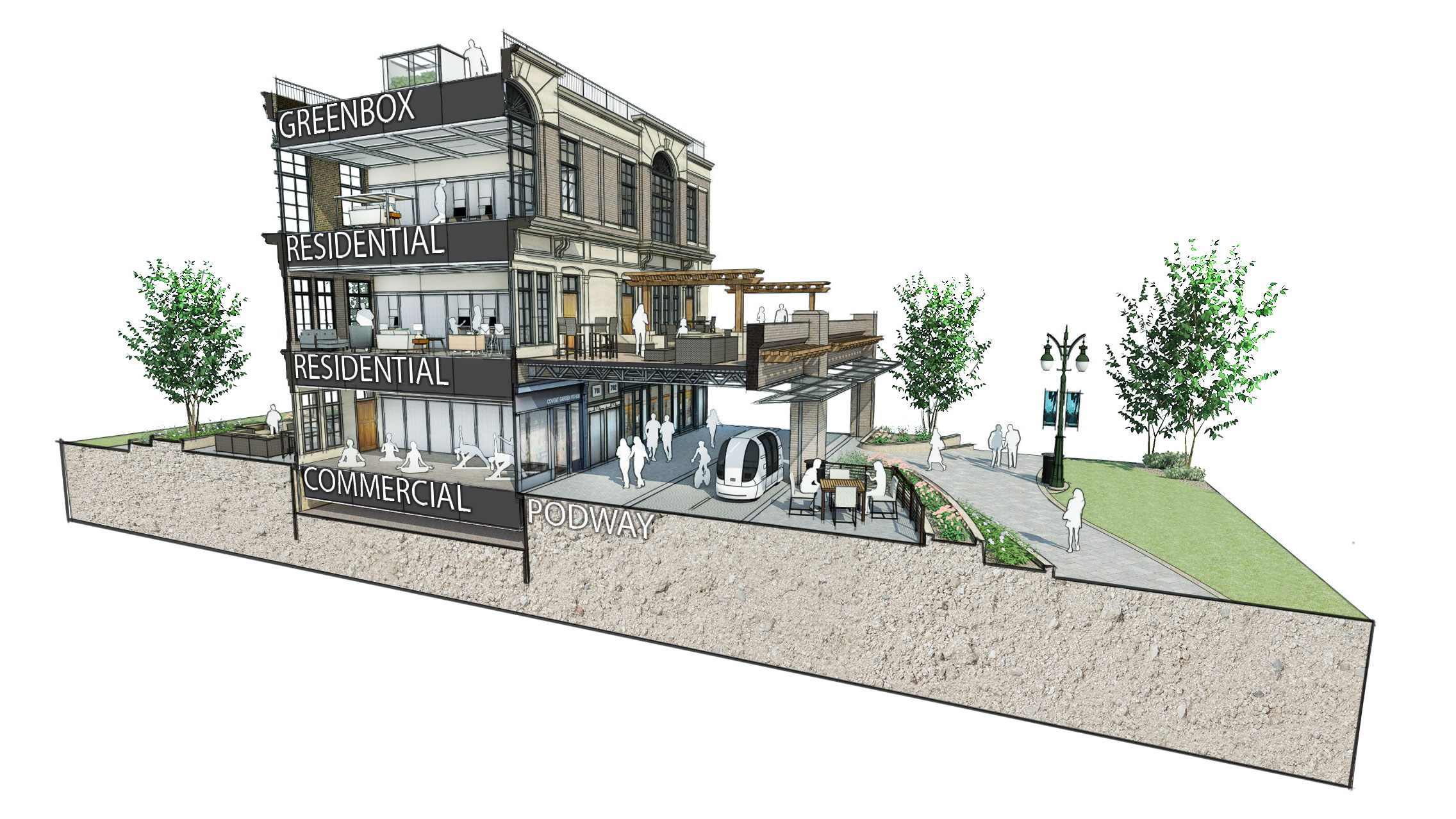

A cross-section of the residences. (Photo: Courtesy The New Vistas Foundation)

The counter-culture movement of the 1960s and ‘70s embraced the book, and acolytes flocked to Vermont to emulate the Nearing lifestyle.

“In the 1970s there were dozens and dozens of communities, and a whole variety of reasons why they were founded,” Calder says. “A lot were anti-war activists, some were radical collectives. There was the Red Clover/News Reel collective in Putney, which had associations with the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground. They organized Free Vermont, which advocated free services for people in need, [and operated] a garage, health clinic and restaurant.”

Calder points out that people were partially drawn to Vermont because the land was cheap, and a lot of the movements were based around farming. While most of the communes have disbanded, a lasting legacy is the organic farm movement Vermont is known for today.

According to Calder, at the peak of the utopian movement in the ‘70s, there were only about 75 communes throughout the state, and the total number of members was well under Hall’s figure of 20,000. (Eventually, Hall believes his communities could sustain 20 million residents in Vermont.)

Sharon, Vermont. (Photo: Doug Kerr/CC BY-SA 2.0)

“The successful communes had a dozen or fewer people,” Calder said.

Hall has bolder ideas. He is touting his development, called NewVistas, as a 21st century model for sustainable living. Each community will be completely self-sufficient: growing their own food in greenhouses and raising animals on the 1,300 acres Hall says will surround each village. The goal is to bring energy consumption down to 1/10th the current levels with no carbon footprint.

The whole idea is anathema to residents, who are horrified at the prospect of 20,000 people moving in and disrupting their long-cherished rural way of life. Locals are resentful of Hall’s attitude that he knows what’s best for the state—long known as environmentally progressive—and its people. Various groups have sprung up to stop Hall in his tracks, including the Alliance for Vermont Communities, which advocates grass roots, slow growth development..

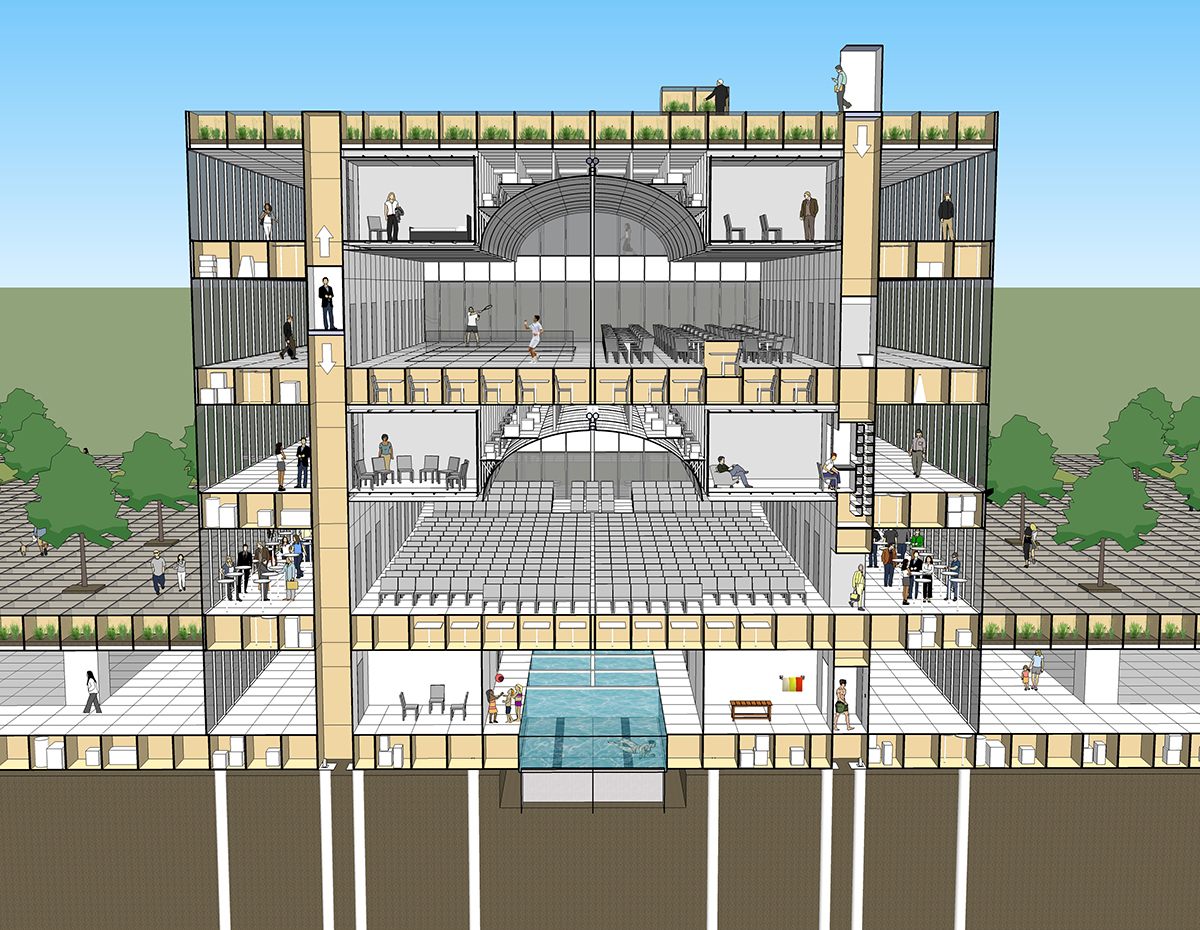

Different community amenities in housing in one building. (Photo: Courtesy The New Vistas Foundation)

Historical precedence may not bode well for Hall’s regimented vision; while noting that a few communities, such as the Red Bird Lesbian Separatists, were very strict, Calder said that any that were restrictive weren’t successful over a long period of time. NewVistas’ plan is to have residents sign over assets to the corporation, and live in futuristic modular apartments, which provide each person with about 200 square-feet of living space. Hall insists that NewVistas will not be religious in nature—the LDS church has come out against the plan—but residents will be taxed on what they consume, and certain items (such as red meat, sugar, coffee and alcohol) will have high “footprint” taxes.

Hall contends that NewVistas is not utopian.

“There will be all kinds of problems, just like in any other community. There is no objective to be a perfect system. The objective is to have a better system than we currently have,” says Hall.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook