The Enduring Legacy of the Worcester Whirlwind

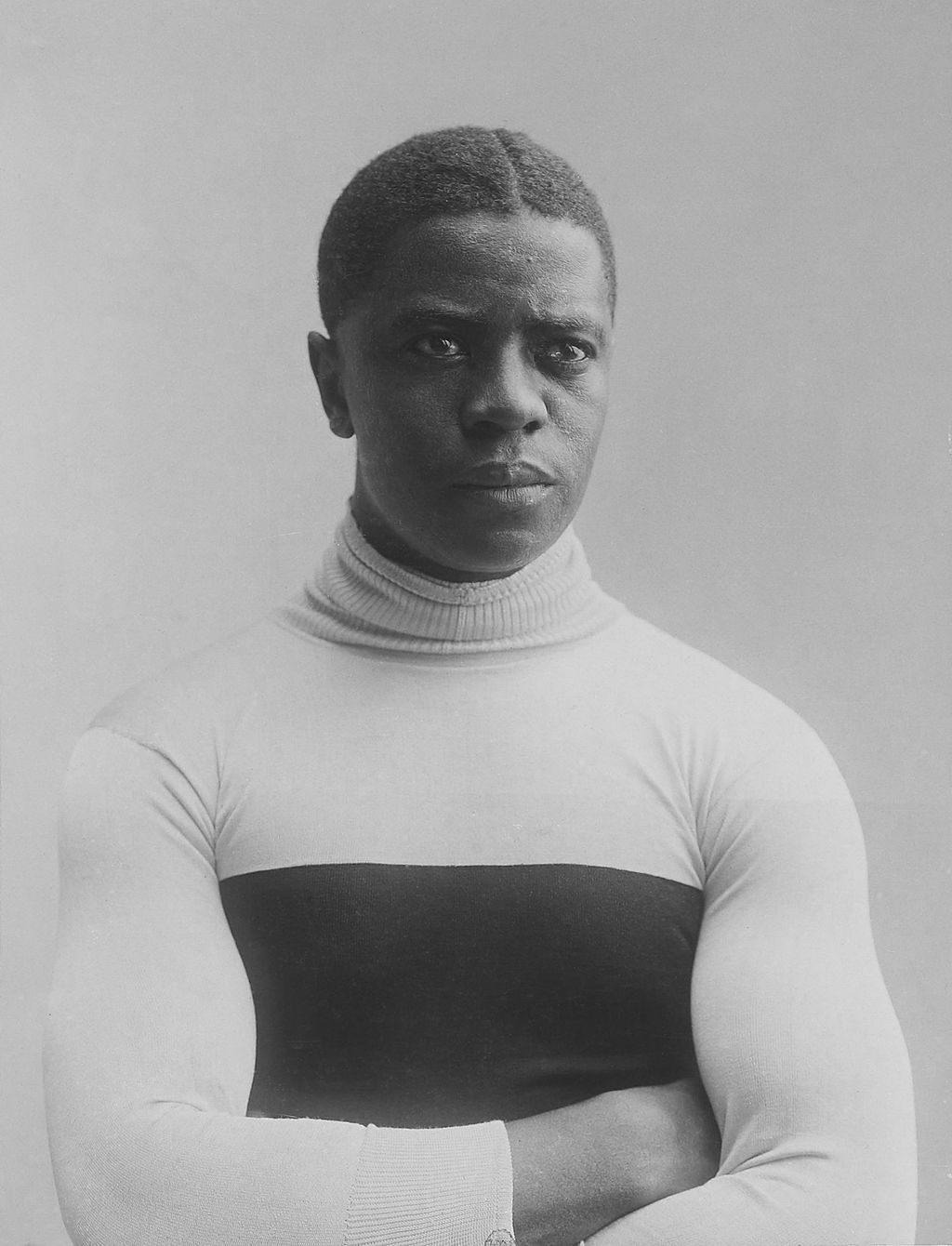

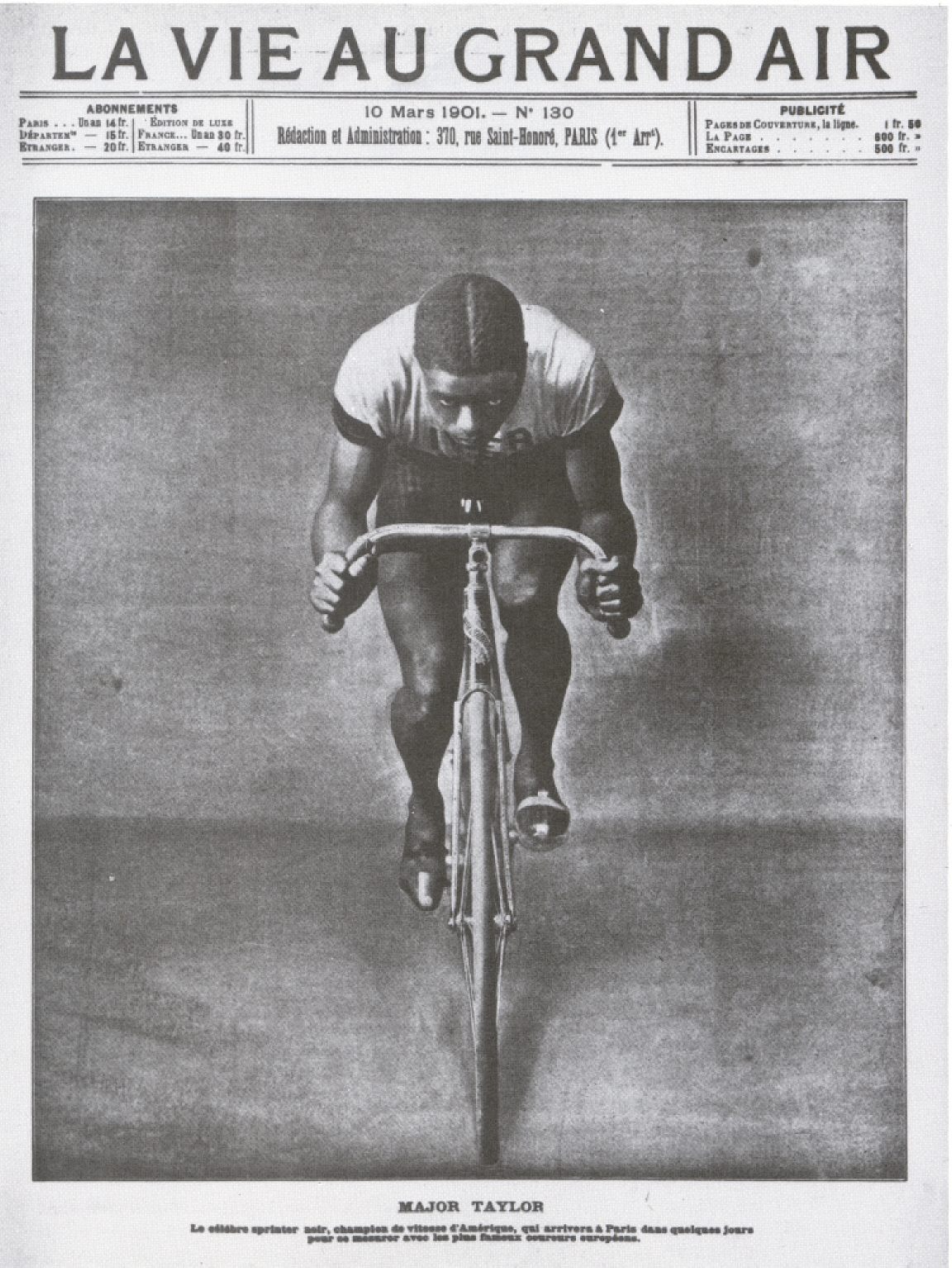

Cyclist Marshall W. “Major” Taylor was the first internationally famous African-American athlete.

Every year near the end of July, a high-spirited group of cyclists gathers at the bottom of George Street in Worcester, Massachusetts. One at a time, each athlete eases up to the starting line, cranes his or her neck up at the steep incline ahead, waits for the honk of an air horn—and then pedals like mad, straight uphill. “We’ve had a unicycle, tandem bikes, a three-seater bike,” recalls Lynne Tolman of the Major Taylor Association, who runs the event. “BMX bikes, road bikes, mountain bikes.” No one is turned away.

The George Street Challenge—an uphill sprint that tends to take anywhere from thirty to sixty seconds, Tolman says—is a far cry from most bike events, which usually go at least a few miles. But it’s a fitting tribute to the athlete it honors: Marshall W. “Major” Taylor, an African-American speed cyclist who was, for the first decade of the 20th century, the fastest man in the world. A longtime Worcester resident, Taylor himself biked up George Street as part of his training.

More than that, the requirements of the race—all alone, straight uphill, as fast as you can—aptly parallel what Taylor had to do to achieve success, in a time of Jim Crow laws and violent discrimination. “Some people call him the Jackie Robinson of cycling, but this was fifty years before Jackie Robinson,” says Tolman. “We say it should be the other way around—Jackie Robinson was the Major Taylor of baseball.”

Taylor was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1878, and from an early age he found that cycling opened doors. He got his first bike at eight years old, a gift from his father’s wealthy employers so that he could keep up with his best friend—their son Dan—and the rest of a gaggle of local kids. After Dan and his family moved to Chicago, the newly lonely Taylor began working as a delivery boy and teaching himself a variety of bike tricks in his spare time. By the time he was a preteen, he had landed a job at a local repair shop—sweeping the store in the morning, and performing a stunt show on the sidewalk every afternoon. (His employer dressed him in a military uniform for these shows, which is how he earned the nickname “Major.”)

Some doors, though, remained firmly shut. Despite his dedication to athletics, he was barred entrance from the local Y.M.C.A. “It was there that I was first introduced to that dreadful monster prejudice, which became my biggest foe,” Taylor wrote in his 1928 autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World. “How my poor little heart would ache to think that I was denied an opportunity to exercise and develop my muscles in the same manner as [my friends], and for really no reason that I was responsible for.”

The inability to train like the others made the young biker less-than-confident in his racing abilities. Soon afterward, though, those abilities were tested—by accident. When Taylor’s boss saw him among the crowd of spectators at the city’s annual ten-mile road race, he gestured his employee to the starting line. “Just ride up a little way, it will please the crowd, and you can come back as soon as you get tired,” Taylor remembered his boss saying. He got tired—but he kept going. Despite his youth, he beat the field by six seconds, and went home with the first of what became scores of gold medals.

Taylor never looked back. Throughout the next few years, he entered any race he could find, winning at distances ranging from to one to 75 miles. He soon found a mentor in Louis D. “Birdie” Munger, an accomplished racer who had recently retired to start a bicycle-building company. Munger built the young speedster a state-of-the-art racing bike, and brought him to work out with local high school teams.

But the more his star rose, the more some people tried to cloud it over. Taylor was barred from certain competitions, and all local bicycle clubs, due to his race. “He was killing it in all the black races, but he didn’t want to be only the black champion,” says Tolman. “He wanted to be the fastest of all.”

So in the fall of 1895, when Taylor was 17, he and Munger moved to Worcester. There, Taylor joined the all-black Albion Cycle Club, began piling up wins in local races, and worked out at the Y.M.C.A. with no problems. “I shall always be grateful to Worcester, as I am firmly convinced that I would shortly have dropped riding … were it not for the cordial manner in which the people received me,” he later wrote.

The next year, at age 18, Taylor went pro. The life of a star cyclist was exciting: Taylor raced for huge crowds at Madison Square Garden, and gained a number of famous fans, including Teddy Roosevelt. It was lucrative: by 1900, he was earning $30,000 a year, far more than most athletes of the day.

But it was also a dangerous life—far more so for Taylor than for his white competitors. Besides sports-related threats—such as the hallucinatory fatigue that set in during a six-day endurance race—Taylor faced discrimination from cycling groups and violence from fellow riders. Members of one major racing association, the League of American Wheelmen, tried to ban him from all tracks under their jurisdiction. While they did not succeed, individual arenas from Philadelphia to Indiana refused to let him race.

Other cyclists elbowed or shoved him during races. After one Bostonian rival, W.E. Becker, lost to him, he threw Taylor from his bike and choked him “into a state of insensibility.” Persistent threats meant that Taylor was sometimes reluctant to ride at all. Once, a training stint in Georgia was cut short after he received an intimidating letter, illustrated with a skull and crossbones, from an anonymous group of “White Riders.” Hotels and restaurants also regularly barred him entry, which meant that while his competitors were relaxing and refueling, he would be searching a city for a bed and a meal. “It would be difficult for me … to call to mind all the vicious attempts that were made in vain to eliminate me from bicycle racing,” Taylor wrote.

Despite this adversity, Taylor continued to tear up the track and to earn his sobriquet, the Worcester Whirlwind. He racked up world record after world record—at one point, he held seven of them, in events ranging from the quarter-mile to the two-mile.

In 1899, he won the one-mile sprint at the ICA Cycling World Championships in Montreal, making him the first ever African-American world champion athlete. In 1902, he set off on a tour of Europe and Australia, leaving a string of fans in his wake. At the time—before automobile and airplane races replaced bicycling as the speedy spectacle of choice—watching him was an unmatchable thrill. “He was really the fastest human on the planet,” says Tolman.

By the time he retired—in 1910, at the age of 32—he had married and had a daughter. He had saved a lot of money. He was ready to prop up his legs (which had been sore pretty much continuously since that first race, when he was 13) and relax at his home in Worcester. But it was not to be. Lacking a high school degree, he was denied admittance to Worcester Polytechnic Institute. The stock market crash of 1929 wiped out most of his savings, and his marriage broke up. He spent six years writing his autobiography, and many more selling it out of the back of his truck, before he died at 53 in a Chicago hospital. He was buried nearby at Mount Glenwood Cemetery, in an unmarked grave.

A few years later, some of his former competitors got together and had a proper marker put at the site. “Still, he remained forgotten for much of the 20th century,” says Tolman. It’s only in recent decades that his contributions to the sport of cycling—and to American history—have begun to gain wide recognition. In 1982, Indianapolis unveiled the Major Taylor Velodrome, an open-air bicycle track that hosts races every summer. Fans across the country, from Pittsburgh to San Diego, have started Major Taylor Cycling Clubs—“not only remembering Taylor and his story, but also working towards diversity and equity in cycling,” says Tolman.

Thanks to the efforts of the Major Taylor Association, Worcester is now home to a bronze statue of Taylor (the first statue of an African American individual in the entire city) as well as a Major Taylor Road. And then there’s the George Street Challenge—a fitting way to pay tribute to a great man, by putting oneself ever-so-briefly in his cycling shoes.

The annual George Street Challenge starts at 10:00 a.m. on July 23, 2017, at the intersection of Main and George streets in Worcester, Massachusetts. Tickets are available here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook