The First American Woman to Win an Olympic Championship Didn’t Even Know It

Margaret Abbott spent her entire life unaware that she had won the top golf prize at the 1900 games.

Margaret Abbott, the first American female Olympic champion. (Photo: Public Domain)

The first American woman to win an Olympic gold medal wasn’t aware of what she’d won. In fact, records suggest she went her entire life oblivious to her historic achievement—and if it weren’t for one professor’s decade of detective work, the story of top prizewinner Margaret Abbott would still be unknown to the world.

The first modern Olympics took place in 1896. The Frenchman who revived the modern games, Pierre de Coubertin, wanted to restrict them to men in tribute to the ancient Olympic games. However, at the 1900 Paris Olympics, a handful of women managed to sneak or stumble into the competition—22 of them, out of a total 997 athletes. These 22 women competed in five socially acceptable, non-contact sports: tennis, sailing, croquet, equestrianism, and golf—the first time that golf appeared at the Olympic Games, and one of the last for over a century. (The sport returned to the Olympics for the 2016 Rio Games.)

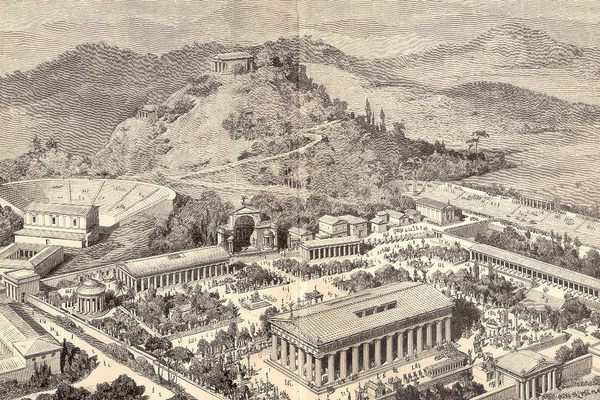

The 1900 Olympics were seen more as a sideshow of the Paris Exhibition, or Exposition Universelle (also referred to as the World’s Fair) than its own independent event. The competitions stretched over six months, took place at shoddy venues lacking proper equipment, and featured some oddities such as tug of war, kite flying, and pigeon racing.

To many, the 1900 Paris Olympics was mostly a sideshow to the World Exposition. (Photo: Public Domain)

Paula Welch, professor emerita at the University of Florida and member of the Olympic Board of Directors, first came upon Margaret Abbott’s name—misspelled Abbot—on a plaque in the McArthur Room at the United States Olympic Committee’s headquarters in New York City. Displayed alongside the names of all of America’s Olympic champions, the plaque listed Abbott as the winner of the ladies’ singles Olympic 1900 golf championship. However, not only had Welch never encountered Abbott’s name before, but she also couldn’t find anybody who knew anything about her.

After finishing her dissertation on American women in the Olympics, Welch, while teaching and coaching full time, spent a full decade tracking down clues about Abbott’s life. After discovering that Abbott had been living in Chicago at the time, Welch pored through old issues of the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Sun Daily.

Abbott won the Olympic championship on October 4, 1900, so Welch scanned for reports starting on October 1. Going back further, she found that Abbott had begun playing at the Chicago Golf Club in the 1890s, coached by several talented male amateurs. Welch notes that any mention of Abbott’s golfing always showed up in the “Society” section, rather than with the sports reporting.

Paris around the time of the Exposition. (Photo: Alphonse Liébert/Public Domain)

Every time she went to a conference, Welch would go to that city’s library and look at newspapers. She looked through the city directories and bluebooks at the Chicago Historical Society and visited the Chicago Golf Club. There was no microfilm for the Chicago Daily, she would have the massive folders of the paper sent to the university, load them into the trunk of her car, and read page after page of things that Abbott did when she was a young woman. “I just looked through, picking up as much as I could, anything that would help me learn more about her,” says Welch.

One golf publication happened to mention a golf trip that Abbott and her husband had taken to St. Augustine, Florida in the 1920s. In an official report issued by Chicagoan A.G. Spalding, the Director of Sports for the United States at the Paris Exposition of 1900, Margaret Abbott was listed as the winner of the women’s golf competition, with Americans Polly Whittier and Hugar Pratt placing second and third.

Women were far too often onlookers, not athletes themselves. (Photo: Library of Congress LC-DIG-hec-30219)

The search didn’t stop with newspaper archives. Welch also ordered Abbott’s death certificate—which is how she learned that Abbott was born in Calcutta, India, before moving to Boston and then Chicago—and tracked down Abbott’s sons. “It was absolutely the most fun, interesting experience,” says Welch.

Welch knew that one of Abbott’s sons was a screenwriter named Philip Dunne who had attended Harvard, so she wrote to Harvard for Dunne’s address. All of this, Welch points out, took place long before the internet, which meant that after hearing back from Harvard and sending Dunne a letter, she could only sit and hope for a reply.

Once Dunne sent Welch his phone number, she called him up. Partway through the conversation, Welch asked, “Did you realize that your mother won the Olympic golf championship?” He’d had no idea.

The 1900 Olympics featured Tug of War as a competitive event. (Photo: Public Domain)

Abbott was not unique in this—since the 1900 Olympics were so overshadowed by the Paris Exposition, a number of athletes were unaware of the details of what was going on. One wonders, then, how Abbott found herself competing in the Olympics in the first place.

“She showed up,” says Welch. She wasn’t listed as a member of the U.S. Olympic team, but because she was in Paris at the time—on an extended visit to study art, as was common of well-to-do young ladies—and she’d previously competed in the French golf championship, she happened to find out that there was a golf competition going on.

Her mother, Mary Ives Abbott, entered the competition as well—the first and only time in Olympic history that a mother and daughter competed in the same sport in the same event at the same time, says Welch. American women swept first, second, and third place, Abbott earning not a gold medal, but a gilded porcelain bowl, in a nod to the Exposition.

These medallions from the Exposition Universelle looked more like Olympic medals than the prizes most athletes received that year. (Photo: cgb/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Abbott passed away in 1955 seemingly unaware of the milestone she’d set. “I guess we could say that she really was a pioneer and a pathfinder,” says Welch. “It was a great accomplishment, and certainly wasn’t for any award or publicity—but for genuine love of the game in the true era of amateur sport.”

Since Margaret and her mother Mary Abbott began breaking ground in 1900, the number of female athletes has slowly increased; in 1924, over 100 women made up 4.6 percent of the competitors, and in 2012, all participating nations featured female athletes for the first time.

There’s still room to grow, but also room for inspiration—from today’s greats to yesterday’s forgotten champions—Margaret Abbott among them.

Update 8/11: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the 1900 games saw ”the first and last” golf competitions at the Olympics. After being retired in 1904, golf returned to the Olympics in 2016. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook