Vienna’s Vegetable Orchestra Is a Feast for Your Ears

Inside a group that’s spent 25 years turning beets into beats.

It started with soup. “We were cooking together,” recalls Matthias Meinharter, one of the founding members of the Vienna Vegetable Orchestra. His friend group had an hour-long slot at a student festival they needed to fill and had been brainstorming ways to create music in unexpected ways. “As we were making vegetable soup, we landed on the idea of cooking it on stage and performing a concert with the vegetables while we were doing that.” The Vegetable Orchestra performed its first concert in April 1998: Twelve friends, none of them musicians, all eager to create something new. Before the performance they had turned their favorite vegetables into instruments, coaxing melodies out of carrots, leeks, and lotus roots. Once each instrument had served its purpose, a cook chopped it and added it to the pot of soup simmering on stage.

In the 25 years since, the orchestra has created around 100 instruments, released 4 albums, and performed more than 300 concerts all over the world. They’ve rubbed leeks at the Shanghai Arts Centre, banged on pumpkin drums at the Royal Festival Hall in London, blew through pepper horns at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and rattled bottle gourds at a sold-out 1,800-seat auditorium in Moscow. With time, experience, and growing international recognition, what was supposed to be a one-off performance by a motley group of students became the most unusual export from the City of Music.

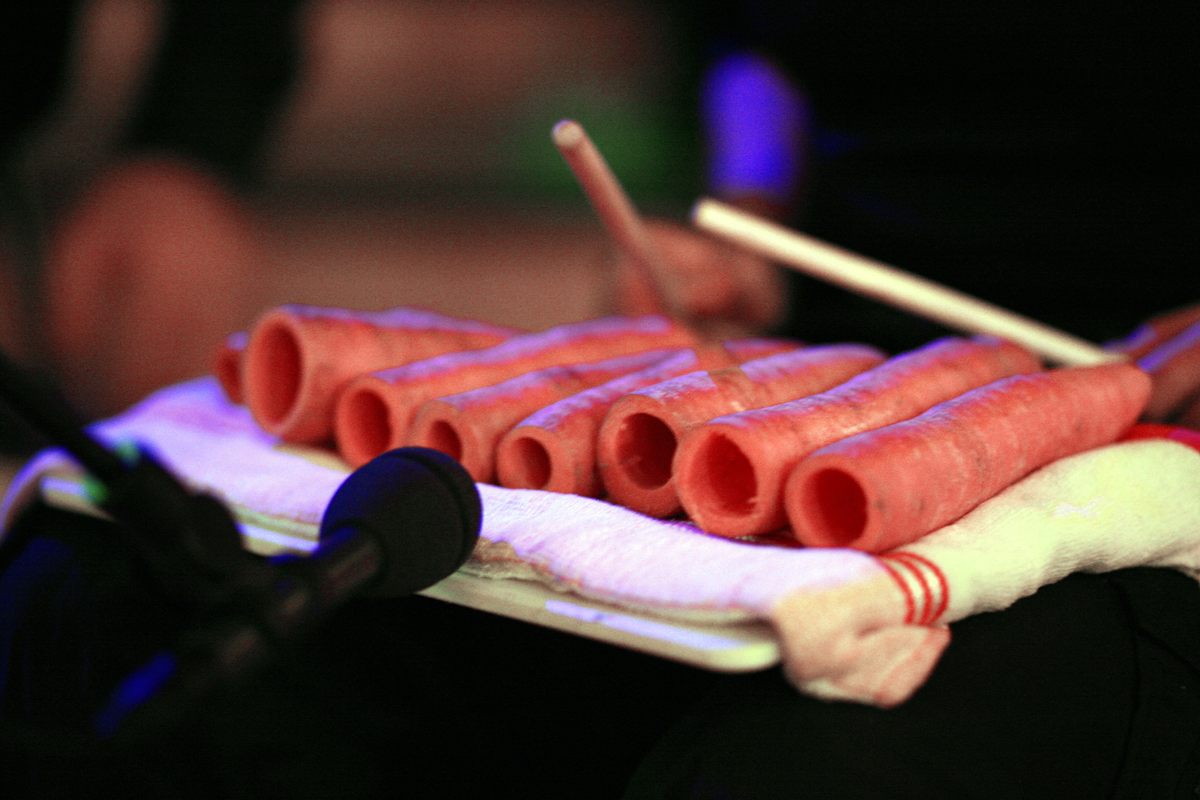

Their mission hasn’t changed: using fresh vegetables to create music, or, more precisely, to create Gemüsik, a portmanteau of the German words for “vegetables” and “music.” Building fresh instruments before each performance requires 100 to 150 kilograms (220 to 330 pounds) of vegetables, two hours of time, and an impressive collection of tools. “We always bring our own equipment—twenty knives, wood and metal drills, longer drills, six power drills…and a first aid kit,” laughs Ingrid Schlögl, a classically trained musician and singer who joined the orchestra in 2004. They reach a venue around noon, carefully inspect the crates of vegetables, build their work stations, then start turning produce into carrot marimbas, celery guitars, pepper horns, cucumber-phones, and anything else required by the evening’s set list. Leftovers from the building process are set aside for the soup. Each orchestra member plays 20 or more instruments per concert, with backups required for the more fragile ones.

Everyone builds their own instruments and they have developed their specialties over time. Schlögl focuses on wind instruments: “It’s quite challenging to play and a lot of experimenting is needed to get the right sound,” she says. “Some prefer building melodic instruments based on classical instruments, like the carrot flute or the pumpkin drum,” says Meinharter. “The other fraction are the purists, and I would count myself among them, who want to highlight the vegetable sounds, when something sounds weird.” His favorite instrument is the leek violin, where one leek serves as the violin and another as the bow, producing a squeaking sound that is more interesting than pleasant. “It’s a sound that can only come from the Vegetable Orchestra. It’s actually not easy to play, you have to lick it and tense it just right,”Meinharter says.

For the audience, a performance by the Vegetable Orchestra is an experience for all the senses. First comes the unmistakable scent of freshly cut vegetables waiting on stage for their musicians. Then there’s the bizarre sight of a group of men and women, all dressed in black, earnestly blowing into pepper trumpets, tapping on pumpkins, and rustling onion skins. Soon, the sound takes over and washes away any skepticism. The Vegetable Orchestra performs at the giddy intersection of playfulness and virtuosity, their unconventional instruments a challenge that lets them conquer new soundscapes. The music roams unbound, sometimes guttural and unmistakably organic, almost indecent, then turning clean and electronic, gently melodious one moment and riotously cacophonous the next.

Even though the carrot flute and leek violin that appeared at the inaugural concert remain dependable parts of the inventory, the way the orchestra approaches them has matured and transformed over the years. “In the early days we were trying to make the vegetables fit our musical compositions; now, it tends to be the other way around,” explains Schlögl. “We are developing towards exploring the music of the vegetables and delving deeper into this element.”

Not all vegetables lend themselves to music; they have to be fresh enough to withstand drilling and shaping, and the right size and shape to produce the required sound. When in Vienna, the orchestra always visits the same greengrocer on Naschmarkt. “They know us so well by now. If we need a pumpkin that has to sound just right, they’ll go back to the storeroom twenty times until we find the right one,” says Schlögl. Gazi Özyürek, who’s been running the stall for 37 years, keeps a photo of the orchestra pinned on the wall in his office. “They’re great customers, always very friendly. What they do with the vegetables afterwards is their business,” he laughs.

When the group performs abroad, things can get tricky. “We send the event organizers a detailed list of what we need. How many of the big carrots, small ones, eggplants, it’s all there. For countries where English might be an issue, we also add photos,” explains Schlögl. “If we’re performing in countries where you can’t get classic European vegetables, we go to the market ourselves to see what’s suitable and what else we could use. Sometimes we also come up with new instruments.” For example, garlic grass found in Asian markets makes a great bass string. Still, crucial produce is sometimes missing and the set list must be changed at the last moment to accommodate it. Other times, they can prepare ahead of time. “For a while, you couldn’t get beer radishes in Russia or large leeks in Italy, so we just packed twenty of them into a suitcase,” remembers Schlögl. These days, the challenges are of a different kind. For their 25-year-anniversary concert, their grocery bill was a whopping 30 percent higher than in previous years.

Contact and condenser microphones help amplify the intimate vegetable sounds. The sound check takes another two hours, during which the orchestra carefully tunes their instruments to each other. “We never play a piece in the same pitch, because we get different sounds each time. The instruments also change their tonality with time as they dry out,” says Schlögl. Creating music with such capricious instruments requires the band members to stay flexible and in the moment.

The orchestra’s performance style has changed drastically over the decades. The original friend group shared an interest in music, but none were musically trained. “The soup was front and center … It was more of a happening than a concert,” remembers Meinharter, who works as a performance artist. With the arrival of new members with strong musical backgrounds, like Schlögl, the music started to take center stage, but the interdisciplinary character of the orchestra remains crucial. Today, the orchestra has 10 members from different artistic fields, ranging from music and performance to visual arts and literature. They create their musical compositions through an intensely collaborative process and have developed their own system of musical notation. They have no leader and perform without a conductor, relying on body language to communicate during a performance. “We are such individual people, but when we are on stage, we are like one body,” says Schlögl.

Every concert still concludes with a bowl of soup, a nod to the dish that started it all. It’s a way to use up the vegetable parts that weren’t needed, and connect with the audience. “We serve the soup ourselves after the concert,” says Schlögl. “I do it quite often and receive a lot back from the audience, people often share personal things. It’s really great.” It’s not often you get to experience music you can eat, but Meinharter believes that anyone can turn an evening spent cooking with friends into a musical performance: “You just have to open your mind and anything can work, anything can become music, even vegetables!”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook