Why Fake Diaries Can be as Powerful as the Real Thing

(Photo: MorganStudio/shutterstock.com)

(Photo: MorganStudio/shutterstock.com)

Sometime in 1993, Joe Nickell, an investigator of historical, paranormal and forensic mysteries, received a copy of the purported diary of one of the most infamous serial killers, Jack the Ripper. Supposedly written by James Maybrick, the Jack the Ripper suspect, the copy had been sent by Kenneth Rendell, a friend and document expert who was investigating it on behalf of Warner Books. The British publisher had planned to publish the original diary that fall—with an initial print run of 200,000 copies—but was now reconsidering it after The Washington Post questioned its authenticity.

Rendell, who owns a respected gallery in New York City, had helped expose the Hitler diaries back in 1982, and had serious doubts of his own, wanted Nickell to take a second look. Nickell’s first impression wasn’t good.

“I called him back and said, ‘Even from across the ocean I can smell something awry.’ It was full of all this Jack the Ripper cliche and written in this pseudo maniacal tone of ‘how much I love killing people.’ So it was more like a poorly written piece of fiction than the way an actual person writes a diary,” Nickell recalls.

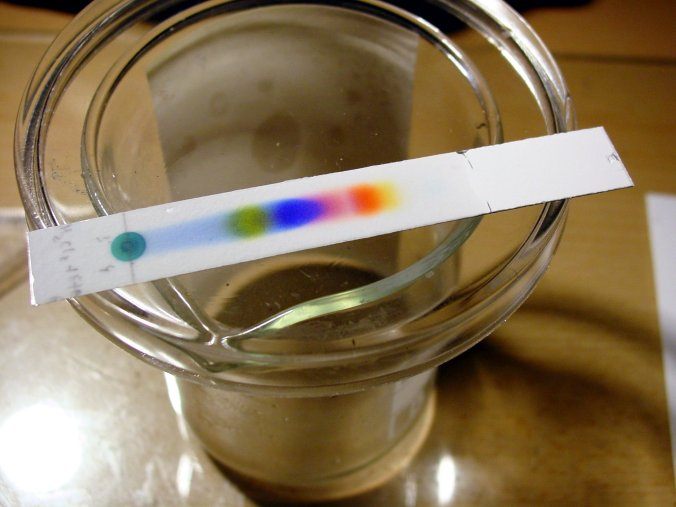

A thin-layer chromatography test, one of the types used to try and verify the Jack the Ripper diary. (Photo: Natrij/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

A thin-layer chromatography test, one of the types used to try and verify the Jack the Ripper diary. (Photo: Natrij/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Still, for the sake of doing a proper investigation, Nickell and Rendell got the publisher to send them the original diary, and assembled a team to examine the ink and paper, as though it were a corpse, or a piece of evidence in a criminal case. Weeks later, they were standing in a rented forensic laboratory in Chicago with “a crackerjack document expert” named Maureen Casey Owens, an ink chemist named Robert Kuraz, and Robert Smith, the would-be publisher. As soon as Smith unveiled the book, the team began to follow the trail of highly suspicious clues.

First there was the writing, which didn’t look genuine to the period. “It was as though someone had tried to make ‘ye old antique-y looking writing’ by adding curlicues,” Nickell recalls. Then there was the document itself. With numerous pages cut out, and the remaining ones stained with paste, the book didn’t look like a diary, but rather an antique scrapbook. This led the team to surmise that whoever had written it had tried to hide its original use.

Jack the Ripper suspect James Maybrick in 1889. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Jack the Ripper suspect James Maybrick in 1889. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But in the end it was a will and a bit of comparative handwriting analysis that provided the most damning piece of evidence. “Jack the Ripper was supposedly a man named James Maybrick, and Maybrick was being shown as the author of this diary,” Nickell says. “The problem was that there was a handwritten will of James Maybrick’s in handwriting which was authentic for the period—and it didn’t have anything in common with the handwriting in the Jack the Ripper diary.”

In the end, Warner didn’t publish the diary. But Hyperion, an American publisher, did. And more than a decade later, a body of literature and articles has grown around it, an evolving debate between Ripperologists and skeptics about the forensic evidence, the veracity of the text, and the mystery of Ripper himself.

According to Nickell, most of the accounts, especially the ones that claim the diary is real, are merely pseudoscience. And yet even the most outrageous fakes (and all their attendant literature and controversy) may be useful. At base, a fake diary is a metanarrative on celebrity culture, opportunism, and a very human desire—the wish to travel through time, get inside each other’s heads, and know what a person was thinking. At their most potent, fake diaries can threaten history itself, and may be as valuable—both historically and monetarily—as the real thing.

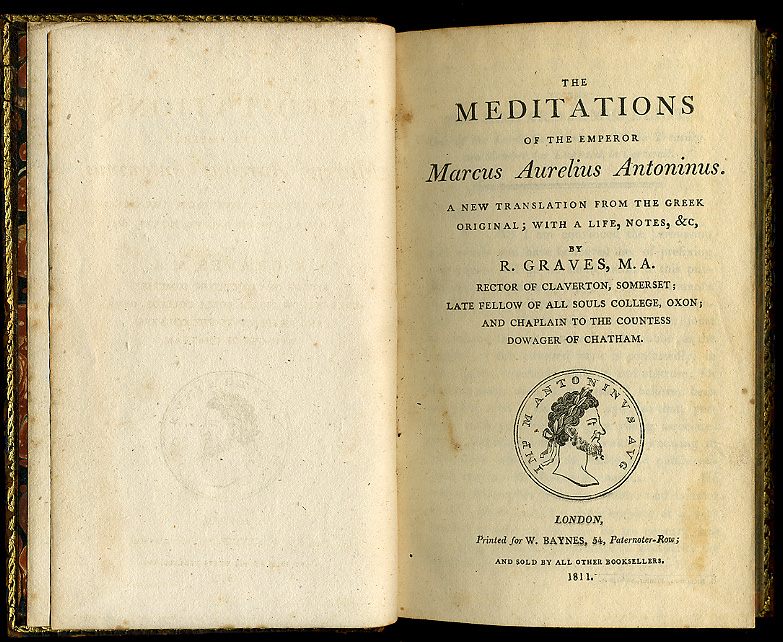

Title page of an 1811 edition of ‘Meditations’ by Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, translated by R. Graves. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Title page of an 1811 edition of ‘Meditations’ by Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, translated by R. Graves. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

As a form, diaries are older than Jesus, with origins in the East and Middle East. “I have seen the diary of the son in law of Prophet Mohammed, Ali ibn Abi Talib....and he mentions how he observes peacocks and how proud they were of themselves,” says Keya Morgan, a document expert in Los Angeles and owner of the largest collection of original Abraham Lincoln photographs in the world. “I have diaries going back to Cuneiform tablets, old Sumerian writings that record what happened, how those people were feeling.” Later, starting in 161 CE, the Roman Empire Marcus Aurelius began writing a series of meditations, recording his personal notes to himself. In the 9th century, the scholar Li Ao kept a journal of his travels through southern China.

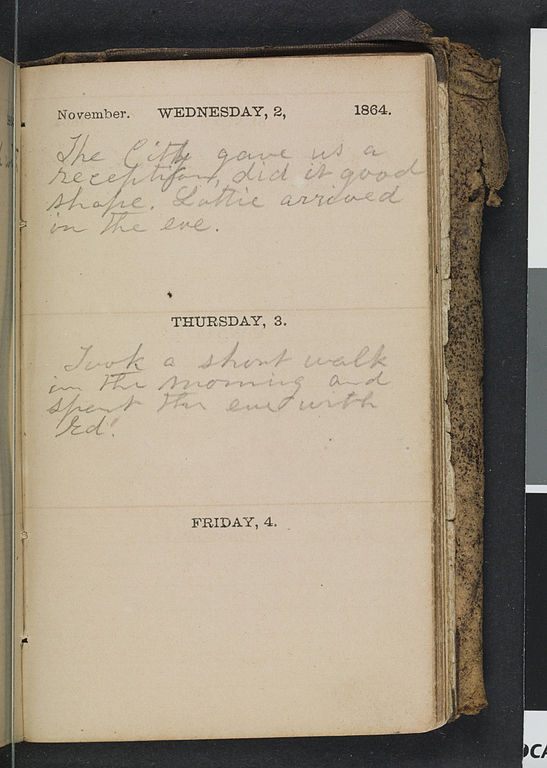

According to document expert Tom Lingenfelter, of the Heritage Collector’s Society in Pennsylvania, diaries gained popularity, as a form, in the 1800s, and especially during the Civil War, in tandem with other sentimental objects, “like locks of hair and lockets.”

In this way, the appeal of a diary is both historical and personal. Even though Morgan has a substantial collection of objects and dresses from Marilyn Monroe’s estate, and is working on a film about her death that touches on her diaries, he says his favorite diaries by far are those of strangers from the Civil War era. “It’s sort of a connection, a time machine.” Morgan says. “I feel like, who am I, no one even knows them anymore, and here I am sitting in my living room privately reading their most intimate thoughts.”

A page from the pocket diary of Isaiah Goddard Hacker, a soldier in the Union Army during the American Civil War, 1864. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A page from the pocket diary of Isaiah Goddard Hacker, a soldier in the Union Army during the American Civil War, 1864. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The power of a diary persists, even when it’s unmasked as a fake. Take the case of Go Ask Alice. It caused a sensation when it was published in 1971 as the anonymous diary of a troubled girl addicted to drugs. And even after it was exposed as a novel, the book maintained its allure, playing into the fears of nervous parents and a lurid curiosity about the secret lives of teenage girls.

Others haunt the corridors of power. When the master forger Mark Hoffman concocted documents and personal letters relating to the Mormon Church—the most explosive of which was the Salamander Letter, describing how an angel had appeared to Joseph Smith in the form of a large white salamander—the church bought many of them them up, and hid the ones that threatened its history away in a vault. And then there were the Hitler diaries, which pretty much rocked the world. The German press called it the historical find of the century but the texts were eventually debunked through a combination of handwriting analysis and the discovery of optical brighteners in the paper stock (Nickell and Morgan’s mentor, Charles Hamilton, a handwriting expert, was one of the first to come forward and question the legitimacy of the diaries based on the pattern of the script). That their crudeness managed to fool so many experts and journalists was a major source of embarrassment, and they continue to be controversial, not least because they underplay Hitler’s role in perpetrating the Holocaust.

Marilyn Monroe in 1952. (Photo: 20th Century Fox)

Marilyn Monroe in 1952. (Photo: 20th Century Fox)

Finally, there’s the the little “red diary” of Marilyn Monroe. According to Morgan, who has conducted some 360 interviews with law enforcement officials, intelligence officers, and Monroe’s friends, it’s a terrible fake, as bad, if not worse, than Jack the Ripper’s. And yet it did more than get people talking. When Ted Jordan took the diary public, he didn’t just spark a frenzy among the media—he prompted officials to reopen the case into her death.

In some cases, the forgers have become as notable as the diaries themselves. The works of Joseph Cosey and Robert Spring, who forged personal letters by Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington, and were experts in handwriting and made their own ink, can fetch hundreds, even thousands of dollars. Hoffman, the forger behind the Mormon documents, produced so many good forgeries that he actually affected the market. “Many of his forgeries, letters he wrote, manuscripts he wrote, are still in universities and private collections. People are very hush-hush about it but he tainted the market in a specific way,” Morgan says. “Bad forgeries are like a bad singer on American Idol: you hear it and go ugh! But a good one, everyone appreciates.”

If good forgeries are getting harder to pull off, Morgan thinks that email has something to do with it. “I deal with hundreds of celebrities, they’re all my friends and clients, and it’s mostly all by text or email. Thats all I have,” Morgan says. “In the future, people are going to say, how do you know this guy really sent this, and it wasn’t their assistant or mother or cousin? With an actual diary you have the paper, the ink, the writing style, the distance between the words and letters, the pattern of the style, if it’s wiggly or circular. There are so many factors to examine,” he adds. “It’s the power of what-if.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook