All the World’s a Puppet Show at France’s Biannual Festival

The international event’s roots go back to a puppeteer who entertained kids during the Nazi occupation.

We first learn the concept, intuitively, as kids: Pretending that objects are alive and making up epic stories about them is fun. A teddy bear can be a medieval warrior-king, a rubber duck an evil sea monster. Perhaps that’s why puppets are such a universal form of art and play that spans eras and cultures across the world. Marionettes—literally “little, little Maries” were often used to tell Bible stories in medieval France. Shadow play is a mainstay in China and Southeast Asia. And Japan’s bunraku is puppet theater with singers, musicians, and half-life-size dolls.

These and more forms of puppet theater are currently on parade in Charleville-Mézières, in northern France’s Ardennes region, at the biannual World Puppet Theater Festival.

The festival was started in 1961 by Jacques Félix, a man who is considered the “father of puppets” in France. He first got to know the art when he worked as a kids’ entertainer in Nazi-occupied France. Félix’s true passion was scouting, but when it was banned by the Nazis, he turned to child entertainment in Nazi-led summer camps.

Today, the 10-day festival attracts around 250 theater companies performing for 170,000 spectators—adults and kids alike—across 50 venues in town. The puppeteers come from all corner of the planet, from Brazil to India and Israel to the United States.

Charleville-Mézières is also home to the International Puppetry Union, a UNESCO-affiliated organization of puppet practitioners, and the International Puppetry Institute and its school, which currently trains 30 international students in a three-year puppetry course.

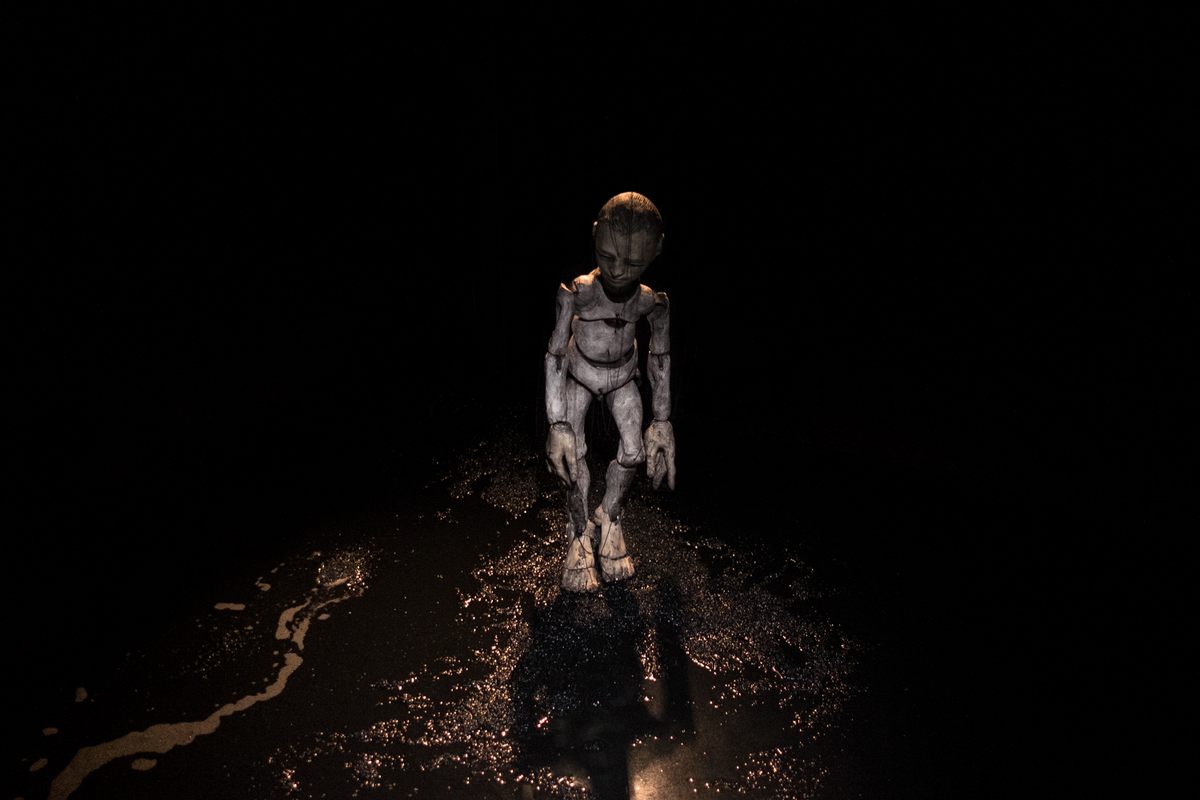

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from current and past iterations of the festivities.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook