A Socialite’s Plot to Assassinate a Corrupt Official in Occupied Shanghai

Zheng Pingru’s scheme involved a fabulous fur coat and ended in tragedy.

For Women’s History Month, Atlas Obscura delves into the world of espionage, where being overlooked and underestimated has been an asset for centuries of women spies. Read about more of history’s hidden Secret Agent Women.

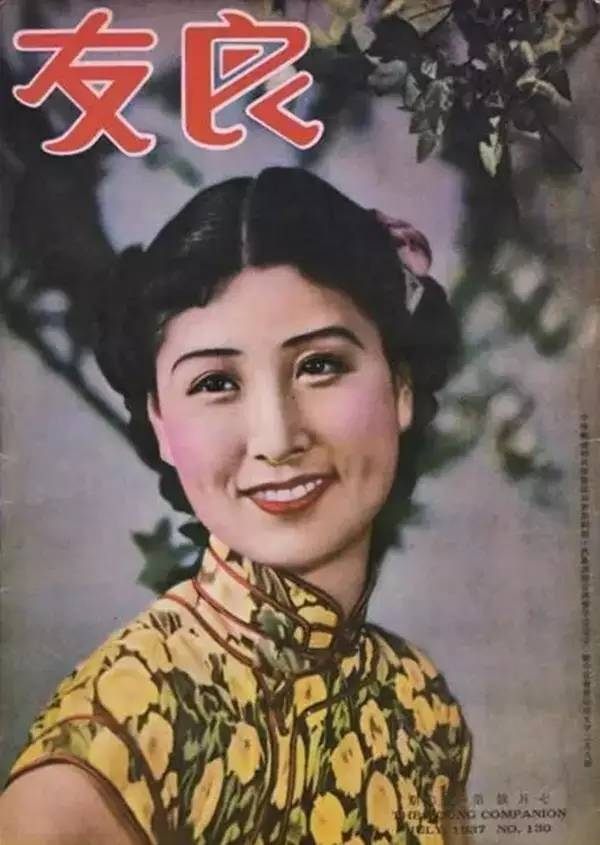

The month before Japanese forces entered Shanghai in summer of 1937 at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Zheng Pingru was featured on the cover of Liángyǒu (translated as The Young Companion for its English edition). The Shanghai-based magazine celebrated the glamorous “modern girl,” the Chinese women who embraced the independence and fashion of the West. Zheng, then about 19 years old, wears a brightly colored qipao and the bobbed finger waves of a flapper. The socialite, who was then gaining fame as a musician and actress, offers a dimpled smile. Three years later, she would be executed for espionage.

Zheng was an ideal intelligence agent in Japanese-occupied Shanghai. Her father was a politician of unquestioned allegiance to the Chinese Nationalist Party, and her older brother, a pilot, died in a Japanese attack—but her mother was of Japanese descent. Zheng spoke fluent Japanese and moved easily among the Japanese elites in the city. Shortly after the invasion, an official from the Chinese Central Investigation and Statistics Bureau approached her and asked her to spy on Ding Mocun, a well-protected Chinese security chief collaborating with Japan.

It took more than a year, but in March 1939, Zheng found a way into his inner circle. “Ding’s predilection for young beauties was well known,” writes Louise Edwards in Women Warriors and Wartime Spies of China. “Pingru was to perform the classic ‘honey-trap’ role. She presented herself at No. 76 [headquarters of a feared Japanese security section] full of charm and elegance and flattered Ding by reminding him that she had been his student while he was the principal at Minguang Middle School.”

Zheng’s mission was to draw Ding out of his protective bubble so that Chinese Central Investigation and Statistics Bureau could assassinate the man, who was complicit in the torture of Chinese dissidents. Her first opportunity came in early December 1939, when the pair had a date. Zheng invited Ding to her home at the end of the evening, but could not woo him inside, where assassins waited. Eleven days later, on December 21, she tried again.

The pair had planned to visit an acquaintance of Ding’s, but on the way to his home, they drove by the Siberian Fur Store on the city’s busiest shopping thoroughfare. Zheng begged Ding to stop at the luxurious furrier and buy her a new coat; two assassins stood outside the shop. Ding agreed to indulge Zheng, but as they entered the shop, something spooked him. He raced back to the car and sped away in a hail of bullets.

It must have been clear to Zheng, whom Ding left behind at the fur shop, that she would now come under suspicion, but she did not waver. A few days later she even went to No. 76 to see Ding. She was arrested upon her arrival, imprisoned, and interrogated for more than a month. Then, in a small forest outside Shanghai, she was shot in the chest.

The full story of Zheng’s espionage would not be known until the end of the war, when Ding was arrested and charged with treason—and even then there were conflicting accounts. Was Zheng to be honored as as a patriot or dismissed as a sex worker? Or both, a Mata Hari of her era?

The question persisted for decades, fueled by author Eileen Chang’s fictionalized novella about the events, Lust, Caution, published in 1983, and director Ang Lee’s feature film of the same name released in 2007.

Finally, in 2009, on the 95th anniversary of Zheng’s birth, the matter was settled when a life-size bronze statue of Zheng, with the Siberian Fur Shop behind her, was erected in a park in Qingpu, west of Shanghai. The monument depicts Zheng at the moment of her execution. But a banner hung at its unveiling showed Zheng as she had been before the Japanese invasion, the plot, the execution: a modern girl with stylish bob and a gentle smile.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook