The 10 Iconic Cemeteries That Made Death Beautiful

The history of the rural cemetery movement, which brought Victorians to picnic among tombstones.

By the 19th century, church graveyards had a worse reputation than you might expect. In addition to their general doom and gloom, they were rife with body snatching, gambling, and prostitution. Add to that the fact that they were literally overflowing, sending decaying matter into water supplies and causing deadly epidemics, and you’ve got a real problem on your hands.

At the same time, social attitudes towards death were shifting. While before, the church graveyard was meant to be a memento mori—a reminder that you, too, would meet your maker someday and so you’d better shape up—in the Victorian era when men, women, children, and the elderly were dying at an unprecedented rate, people didn’t want to be reminded of death and damnation when they buried their dead. They wanted to mourn in peace.

The architect Sir Islington Wren had introduced the idea of a garden-like cemetery on the edge of town as early as 1711, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that rural cemeteries caught on. When they did though, everything about death changed.

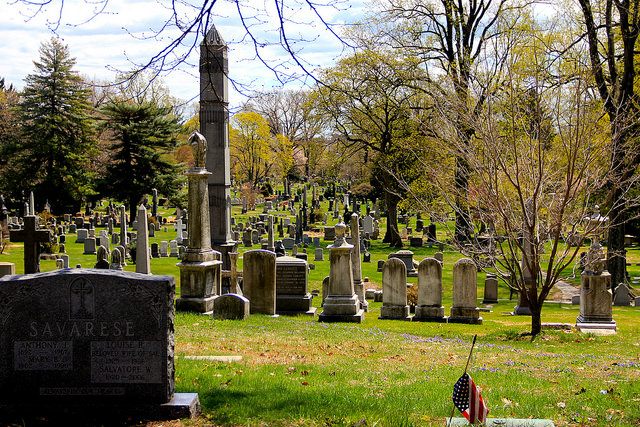

With names like “Green-Wood” and “Forest Lawn,” graveyards came off as places of natural respite, not of decay and foreboding. Grassy lawns, flowering trees, and reflective ponds made them as much a place of repose for the living as for the dead. The skulls and crossbones of 16th century grave markers were replaced by more artistic, interpretive symbols like lambs, lilies, and open books. And unlike the restrictive religious burying grounds, in these new rural cemeteries of the 19th century, municipally operated and religiously unaffiliated, anyone was welcome to be interred.

The living flocked to rural cemeteries in droves. In some places these were among the first parks open to the public, and when they opened Victorians would take day outings to the new cemeteries. Celebrity corpses were a draw, but so were those who became famous in death—tragic young women who threw themselves into rivers and pioneering balloonists who fell from the sky. Memorials, too, gave sculptors and artists a place to showcase their work, some of which became famous in its own right.

Death was never more present than in the Victorian era. But rather than pretend it wasn’t there, people living in the 19th century got cozy with their final fate in bucolic grounds where the notion of beauty in death was celebrated.

1. Père Lachaise Cemetery

PARIS, FRANCE

A fork in the path at Père Lachaise. (Photo: Clayton Parker/CC BY-SA 2.0)

It all started in Paris, a city known for its overflowing catacombs, which was more in need of an expansive burial ground than most. Père Lachaise was established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1804 in response to the squalid church graveyards, and set aside specifically for the purpose of being an organized and beautiful burying ground owned by the city, the first of its kind. The cemetery really gained repute when Molière’s remains were reinterred there. Since then, its dramatic grounds have become known as the final resting place for many tragic misfits: Oscar Wilde is buried there, as are Jim Morrison and Edith Piaf. The classically French monuments, which shrug austerity for romantic, dramatic sculptures, brought tourists along with mourners right from the start.

2. Highgate Cemetery

GREATER LONDON, ENGLAND

The cramped, ivy-covered headstones cast a spell over all those who visit Highgate. (Photo: Atlas Obscura user allison)

Inspired by Père Lachaise, the garden cemeteries of London were soon to follow. Kensal Green Cemetery and Catacombs, West Norwood Cemetery, Brompton Cemetery, Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park, Nunhead Cemetery, and Abney Park (which actually took its cues from American rural cemeteries rather than a European source) were all built in the 1830s and ’40s. Their idyllic beauty became renowned worldwide, and the cemeteries were branded as London’s “Magnificent Seven.”

Highgate was not the first of these to open, but it is the crown jewel. The densely overgrown greenery shrouds the crumbling granite headstones, and the literal “high gates” surrounding the grounds cut off the world outside, making Highgate feel like a secret garden for the dead, equal parts fairytale and horror story. It’s been the set for many movies, plenty of them vampiric, but many visitors still come to the dilapidated cemetery simply to pay their respects to the dead—in particular, the famous ones like Karl Marx.

3. Mount Auburn Cemetery

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

Winding paths in Cambridge’s Mount Auburn Cemetery. (Photo: Daderot/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Winding paths in Cambridge’s Mount Auburn Cemetery. (Photo: Daderot/CC BY-SA 3.0)Although the relatively new cities of the United States were not as crowded with dead as those in Europe, American burial grounds nevertheless trended towards the rural cemetery as well. Following the French and English examples, the first American garden cemetery opened in Cambridge in 1831. Winding paths looped around sunny hillsides, with peaceful gravestones under shady trees.

As if the draw of literary figures like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wasn’t enough, Mount Auburn is also protected by the National Park Service and functions as an arboretum and a wildlife refuge. This distinctly park-like atmosphere set the tone for practically all rural cemeteries to come. With the success of Mount Auburn, idyllic green cemeteries that offered respite to city-dwellers as well as the dead and buried began to crop up all over the U.S.

4. Laurel Hill Cemetery

PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA

Philadelphia merchant William Warner’s monument features a female figure lifting the lid off a coffin so Warner’s soul may escape to heaven. (Photo: dbking/CC BY 2.0)

Not to be bested by Boston, equally historic Philadelphia opened its own rural cemetery a mere four years later. If Mount Auburn was the resting place for American literary figures, Laurel Hill was the garden cemetery for America’s war heroes. Its headstones, much like those in Père Lachaise, tended toward the sculptural and often depicted the veterans and statesmen buried beneath them.

5. Green-Wood Cemetery

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

Graves at Green-Wood. (Photo: Michelle Simoncini/CC BY 2.0)

Shortly after came Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, which was quickly folded into New York City lore. It was instantly a coveted place to spend the afterlife. Hundreds of New York’s famous and infamous are buried at Green-Wood. Just a few of the most notable interred include William and Henry Steinway, F. A. O. Schwarz, Samuel Morse, Leonard Bernstein, Boss Tweed, and Louis Comfort Tiffany. People flocked here to see the graves of these famous people (this was often closer than they could have ever gotten when they were alive), but also to see the resting places of those who became famous in death. These included those who died in the tragic Brooklyn Theatre fire and a young debutante killed in a carriage crash.

The grounds also boast some impressive monuments, including pyramids, mausoleums, and an intricately carved Gothic entranceway that apparently houses a flock of escaped parakeets. The cemetery conducts an extensive series of events (many with Atlas Obscura!), and makes its resources available to the public, including the undertakers’ ledgers.

6. Mount Hope Cemetery

ROCHESTER, NEW YORK

A massive tree in Mount Hope Cemetery. (Photo: Ryan Hyde/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Bucolic Mount Hope Cemetery is home to some of upstate New York’s most famous, many of whom were political pioneers. Susan B. Anthony is buried here, as is Frederick Douglass. Taking full advantage of its park-like atmosphere, the greenery in Mount Hope is as impressive as are its residents. Its towering trees dwarf even the highest obelisks, and the fall foliage is a breathtaking sight. It followed the example set by Mount Auburn, Laurel Hill, and Green-Wood, solidifying park cemeteries as a distinctly American phenomenon.

7. Spring Grove Cemetery

CINCINNATI, OHIO

Sunlight streams through trees and monuments at Spring Grove. (Photo: David Ohmer/CC BY 2.0)

Soon states outside the Northeast caught wind of the trend and the movement spread. It wasn’t just a nicer way to bury the dead, it was a representation of European civilization, and as such any cities that considered themselves metropolises ceased the use of musty church graveyards and opted for new, lush, green garden cemeteries instead.

It wasn’t only trend-following that prompted Cincinnati to open Spring Grove Cemetery though. In the early 1840s a massive cholera epidemic swept the city. As churches grew unable to handle the daily influx of corpses, the city stepped in and opened Spring Grove Cemetery. At first it was just your average burial ground, but in 1855 Cincinnati hired renowned landscaper Adolph Strauch. He dug ponds and lakes with their own islands, planted small forests, and designed a Gothic chapels and mausoleums where there had been practically nothing before. Like those that came before it, Spring Grove instantly became a desirable place to be buried, a lovely place to take an afternoon walk, and one of Cincinnati’s crowning gems.

8. Elmwood Cemetery

MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE

“Snowden’s” tomb at Elmwood Cemetery. (Photo: Atlas Obscura user allison)

If the names of these cemeteries are beginning to read as somewhat generic, it’s because they often didn’t mean anything. Elmwood Cemetery’s name was chosen from a hat.

Like Spring Grove, Elmwood’s population was largely “born” out of a yellow fever epidemic. It took the lives of roughly 5,000 Memphians, about half of which are buried in Elmwood. Because the death toll was so high, many of the dead didn’t have anyone left behind to bury them, and so are interred in a mass grave labeled “No Man’s Land.” Elmwood is the only rural cemetery that has made a regular practice of memorializing the unknowns. Following in the example of the yellow fever grave, there is also a headstone dedicated to fallen Civil War soldiers (both Union and Confederate), enslaved Africans, and people who donated their bodies to science.

9. Cave Hill Cemetery

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

Some of Cave Hill Cemetery’s original graves. (Photo: Garden State Hiker/CC BY 2.0)

While most rural cemeteries were the result of neat city planning, others grew by accident. In the case of Cave Hill Cemetery, it was first farmland purchased by the city to be quarried, but became the site of a “pesthouse” for diseased persons in the first half of the 19th century. Following all the death that came out of that place, the land was dedicated by a Reverend Edward Porter Humphrey. Continuing the thematic trend of the rural cemetery movement, he stated that, “…reason and taste suggest that [this cemetery] should be decorated appropriately by the beautiful productions of our great Creator....”

Unlike most of these cemeteries, Cave Hill continues to inter bodies today. As such, its grounds are a hodgepodge of somber gravestones like the ones seen above, effusive Victorian monuments, and modern interpretations of the sentimental tombs of yesteryear. These include a life-size sculptures of a couple bearing swords, Jesus holding a swing for a little girl, and an eagle and a hawk fighting to the death.

10. Hollywood Cemetery

RICHMOND, VIRGINIA

Graves at Hollywood Cemetery overlooking the James River. (Photo: Andrew Bain/Public Domain)

Like Cave Hill, Hollywood Cemetery was built around an older cemetery, and so it contains elements of pre-Victorian graveyards as well as the flowery effects of a typical garden cemetery. It formally opened during the wave of rural cemeteries in the 1840s, but received most of its burials during the Civil War. It has all the trappings of its companions (rapturous monuments, shady oaks, winding paths), with one colorful addition: a vampire.

Legend has it that following a mysterious railroad tunnel collapse in 1929, a human-like creature covered in blood with jagged teeth and flesh falling off its body was seen creeping into a mausoleum. Ever since, the cemetery has been a popular place for teenagers to sneak into late at night in an attempt to catch a glimpse of the Richmond Vampire. It just goes to show that despite all efforts to strip the dark and depraved from a cemetery’s reputation, some spookiness avails.

The rural cemetery eventually became the de facto model for burial grounds, but it’s easy to forget it wasn’t always this way. As interest in the morbid grows more acceptable and even encouraged, people go to cemeteries not just to mourn or gawk, but to look into the past.

People will always die, and we will always have to do something with their remains. However, cemeteries themselves are becoming a less efficient option of funerary treatment. Burial is space-consuming and embalming is bad for the environment. It’s becoming less and less common to be buried at all, and new cemeteries are almost never opened. As such it’s fascinating to walk through these sumptuous parks that were once the height of innovation and style in funereal treatment. Bring a blanket and make like a Victorian to your nearest rural cemetery to spend some time with the dead.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook