About

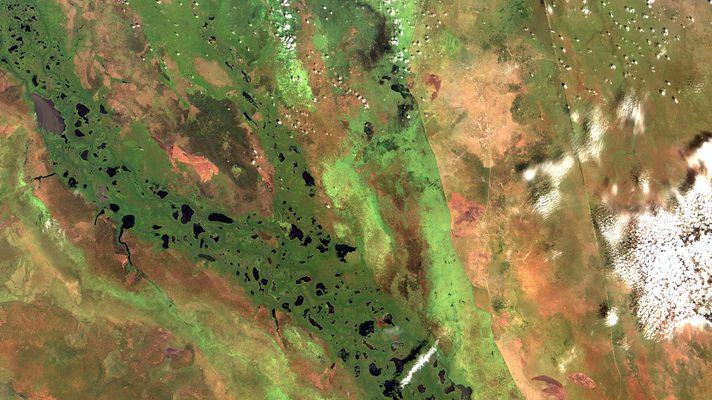

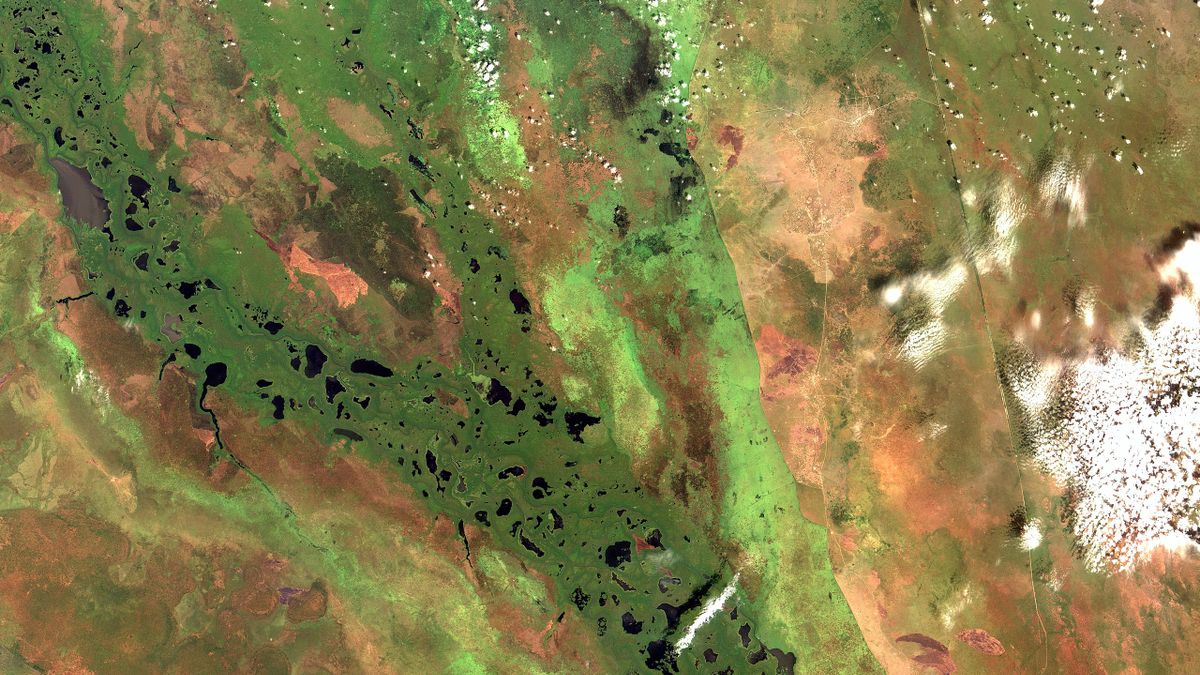

South Sudan's Sudd Wetland, also known as Al-Sudd, is one of the world's largest wetlands, covering more than 35,000 square miles in the north-central part of the country. The White Nile, its many tributaries, and seasonal rainfall sustain the vast wetland. Currently being considered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Sudd is home to a vast array of flora and fauna, including endangered African elephants, an endangered antelope known as the Nile lechwe, and the critically endangered (and highly photogenic) shoebill. The Sudd is also the site of a huge antelope migration every October, including the spectacularly weird Topi.

Approximately 1 million people live in the Sudd Wetland, many of whom come from Indigenous tribes that have inhabited the area for thousands of years. There are the Nuer and Dinka, two pastoralist peoples that make up the largest ethnic groups in South Sudan. Raising cattle is the primary livelihood for both of these groups, and many social rituals incorporate the animals. Husbands-to-be give cattle to family members of the bride, and Nuer priests often settle feuds through the exchange of cattle. In a centuries-old ritual, Dinka boys transition into manhood when they stop milking cows.

Another group, the Shilluk, are primarily sedentary farmers. According to tradition, the physical and spiritual well-being of their chosen leader was tied to the overall prosperity of the land. The Anuak people are also farmers and maintain herds of cattle, sheep, and goats. Like many others, they also fish in the wetlands and set up seasonal fishing villages.

The Neur, Dinka, Shilluk, and Anuak have all adapted to the seasonal changes of the Sudd. The Sudd's dry season, between December to February, often sees nomadic communities move deeper into the wetland to graze their herds and hunt the Sudd’s plentiful fish. Communities, especially the Dinka, will build seasonal, circular homes on naturally-occurring islands in the wetland during the dry season. During the Sudd's wet season, between March to August, many move back out of the Sudd to settlements near water deposits in the savanna.

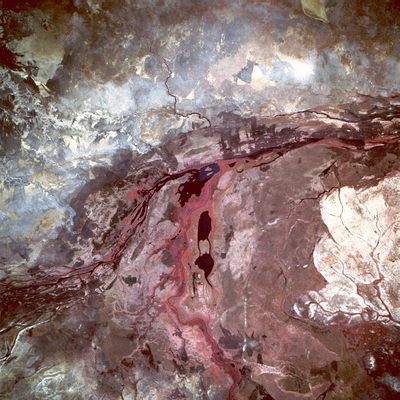

After gaining independence from Sudan in 2011, South Sudan descended into a violent civil war. During the peak of the fighting, the United Nations estimates that 65,000 to 100,000 people escaped into the Sudd, reported National Geographic. For centuries the Sudd, which literally translates to “barrier,” has been a sanctuary for people fleeing violence, slavery, and oppression. But the recent influx of so many people has meant more competition for resources in the Sudd. Foreign oil companies have also secured contracts to mine the Sudd’s naturally-occurring oil deposits, posing yet another risk to the wetland. Initial oil surveying has already polluted the delicate ecosystem. Many hope that if the Sudd does become a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the international status would protect one of South Sudan’s most precious natural wonders.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Most of these communities are extremely private and are not visited by outsiders.

Published

June 24, 2022

Sources

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/sudd-south-sudan

- https://evolution-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/20160913_ei_south-sudan_low-res.pdf

- https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/sudd-flooded-grasslands/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nilot

- https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2461&context=etd

- https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/anuak-threatened-culture

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Shilluk

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nuer

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Al-Sudd

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6276/