Why Are There So Many Female Ghosts?

Female ghosts seem to dominate the afterlife. Whether the spirits are real or not, the reasons for the disparity could be revealing.

If you drive south of San Antonio, Texas on Applewhite Road, past the fire station and the Toyota plant, and pull over just shy of the Medina River, you can walk a few hundred feet through tranquil forest and patchy sunlight to where a small bridge crosses a burbling stream just out of sight of the highway.

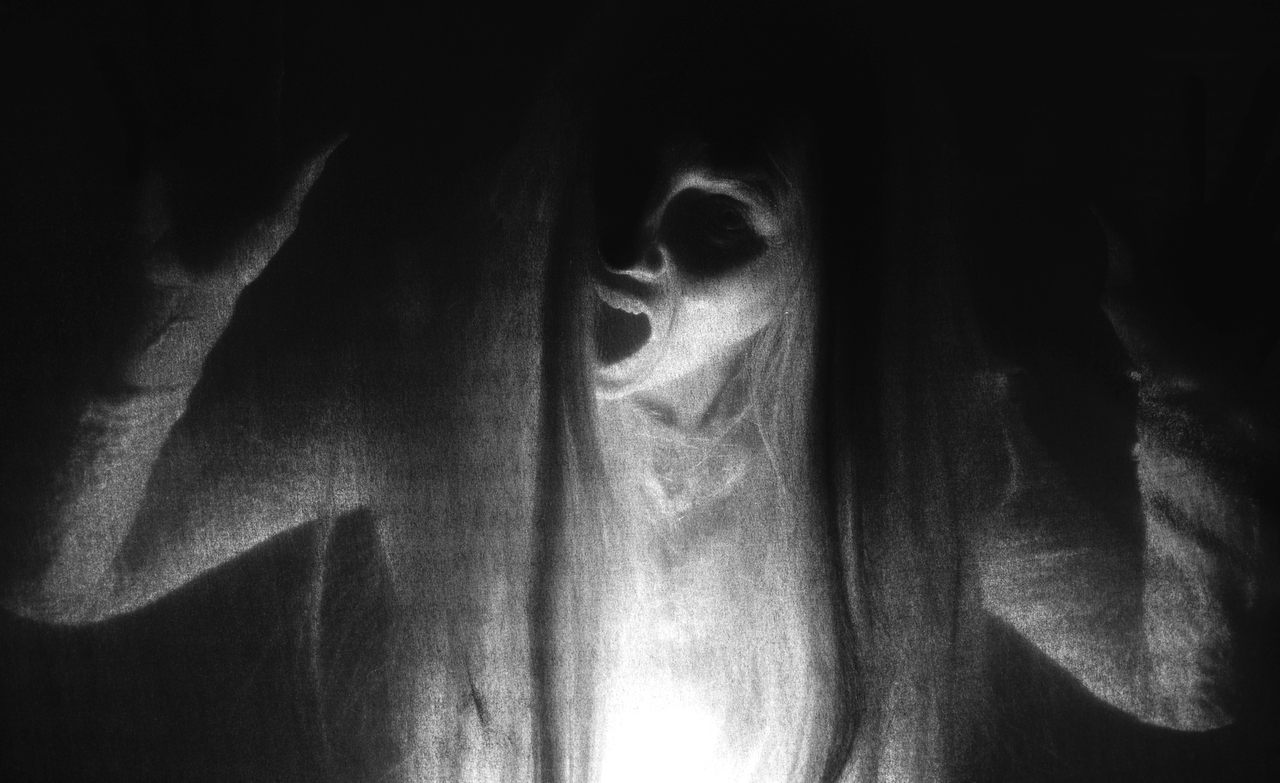

There, on certain evenings, when the last rays of light cut through deepening shadows, and the sound of the wind has faded from the tree tops, you may have an experience you cannot easily explain. A rustle in the undergrowth, a flicker in your vision, the distinct clopping of hooves. You may not see her, but, as many visitors report, the Donkey Lady was nearby.

This quirkily-named phantom has for decades been said to haunt the San Antonio bridge. Visitors report the sound of hoofbeats and distant screams and the presence of a specter, her face and body disfigured, lurking nearby. Some even claim to have found hoofprints on their cars. Despite the apparent danger, or perhaps because of it, the Donkey Lady bridge has become a popular spot with locals eager for a ghostly encounter, and a tourist attraction of sorts.

“When I moved to San Antonio in 2002, the first stop that my friends brought me to [was] not to the Fiesta, or the Riverwalk, or even the Alamo, it was the Donkey Lady bridge,” says Marisela Barrera, a San Antonio-based artist.

As one version of the story goes, the Donkey Lady is the ghost of a woman who lived outside of San Antonio more than a century ago, raising donkeys on a farm by herself. She died in a fire that left her body horribly maimed and, unable to find peace, her spirit lingers near the bridge.

For Barrera, this supernatural persistence, similar in some ways to the stubborn animals the unnamed woman raised, is a measure of her spirit’s strength.

“The Donkey Lady stands her ground,” she says. “She’s so strong-willed that she could survive despite her circumstances.”

Real or not, the Donkey Lady is also representative of a curious trend found throughout American folklore. A significant proportion of ghosts, from the omnipresent Lady in White to the spectral “Mrs. Spencer” who haunted Joan Rivers’ New York apartment, are women.

The Afterlife is Female

There is no conclusive database of hauntings to reference, of course (though perhaps there should be). But browse through lists of haunted places and famous ghosts, and you’ll notice a distinct bias.

“It does really seem that the numbers are skewed more towards female ghosts,” says Leanna Renee Hieber, a writer and co-author of A Haunted History of Invisible Women: True Stories of America’s Ghosts.

Potential explanations range from the supernatural to the mundane. Do women’s souls have more sticking power? Are women more motivated to return after their mortal coil has been shuffled? Are female ghosts more memorable to us? Or perhaps we’re more likely to think of a woman in a white dress when we see an errant patch of fog (or ectoplasm).

It could be, as Gothic master Edgar Allan Poe once wrote, that dead women are simply more emotionally resonant than dead men.

“The death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world,” Poe wrote in his essay “The Philosophy of Composition.”

Whatever the reason, the preponderance of ghostly women is interesting for much the same reasons that ghosts themselves are interesting, regardless of your belief in the supernatural.

“There’s a saying that seeing is believing, but it’s equally true that believing is seeing,” says Anna Stone, a psychologist and researcher at the University of East London “Our ghosts are a reflection of our own beliefs about what ought to be happening, our own desires.”

What then, is the common thread that unites feminine specters like Gertrude Tredwell, who haunts the Merchant’s House in New York City, the Bell Witch that tormented the Bell family in Tennessee, and the undead, forlorn lover said to claw at cars passing over Emily’s Bridge in Vermont? Like women’s evolving role in society, the answer is complex.

“There’s just like layers and layers and layers of the way female identity, as it’s constructed in Western society in the last two to three centuries, overlaps and intersects with the deathly,” says Andrea Janes, who runs the ghost tour company Boroughs of the Dead, and co-wrote A Haunted History of Invisible Women with Hieber.

Who’s Afraid of a Woman Ghost?

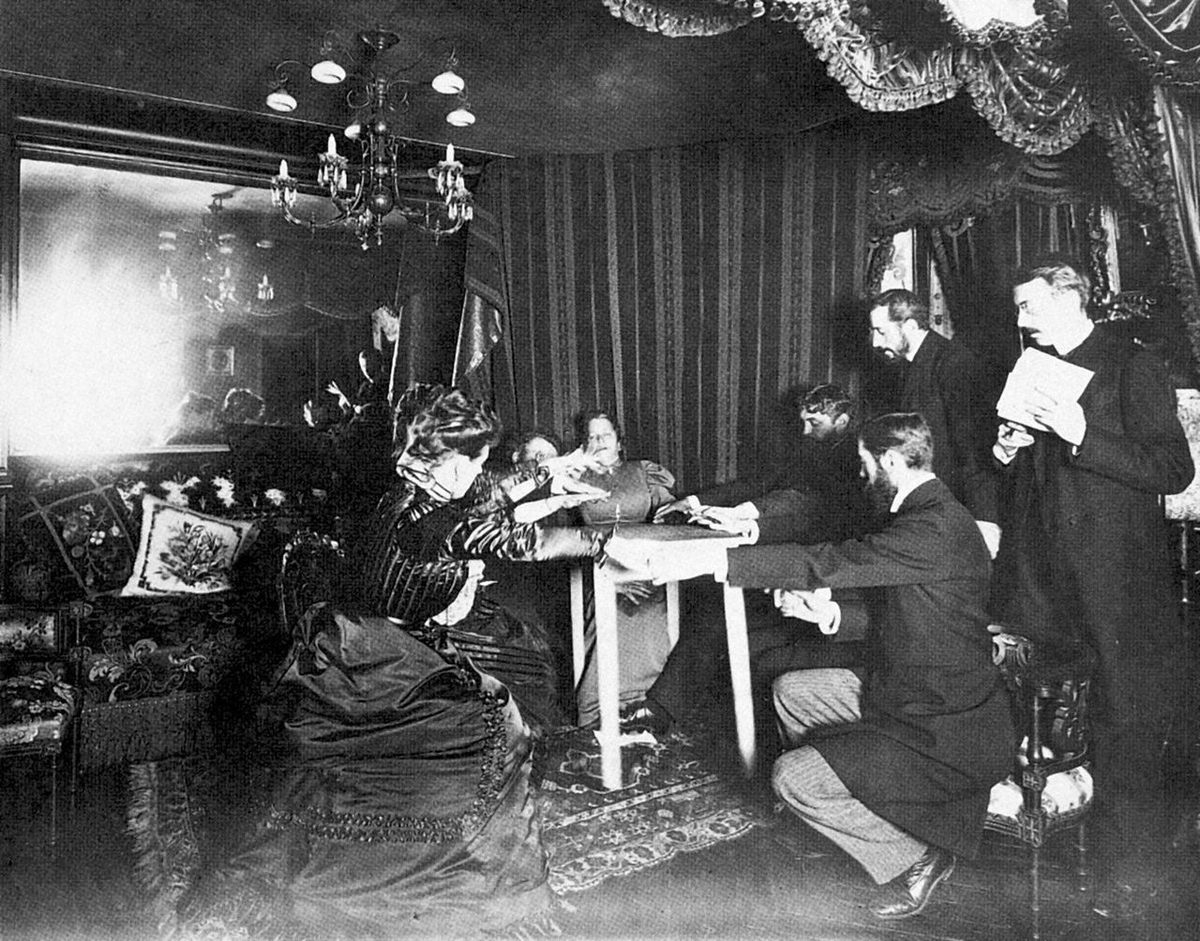

One big factor could be the gravitational pull of the Victorian era, when ghost stories abounded, on present-day culture. It was a time when gender roles were becoming tightly confined, Hieber says, in response to a changing, industrializing society.

That meant women were more tightly tied to the domestic sphere, and their houses, even after death. In a time before funeral parlors, it was often women who washed and prepared the dead, further strengthening their connection with death. Add to that a predilection toward romanticizing death, as Poe did, and you’ve got a formula for memorable dead women—and their ghosts.

Women also took a more central role in the otherworldly around this time, Hieber says, from their involvement with the spiritualist movement as mediums, to a growing cadre of 19th-century authors like Rhoda Broughton and Charlotte Ridell penning stories populated by phantasms and spirits, who were often women.

“The pump was primed, as it were, for women to be involved in ghost lore because they had been directly involved in creating it,” Hieber says.

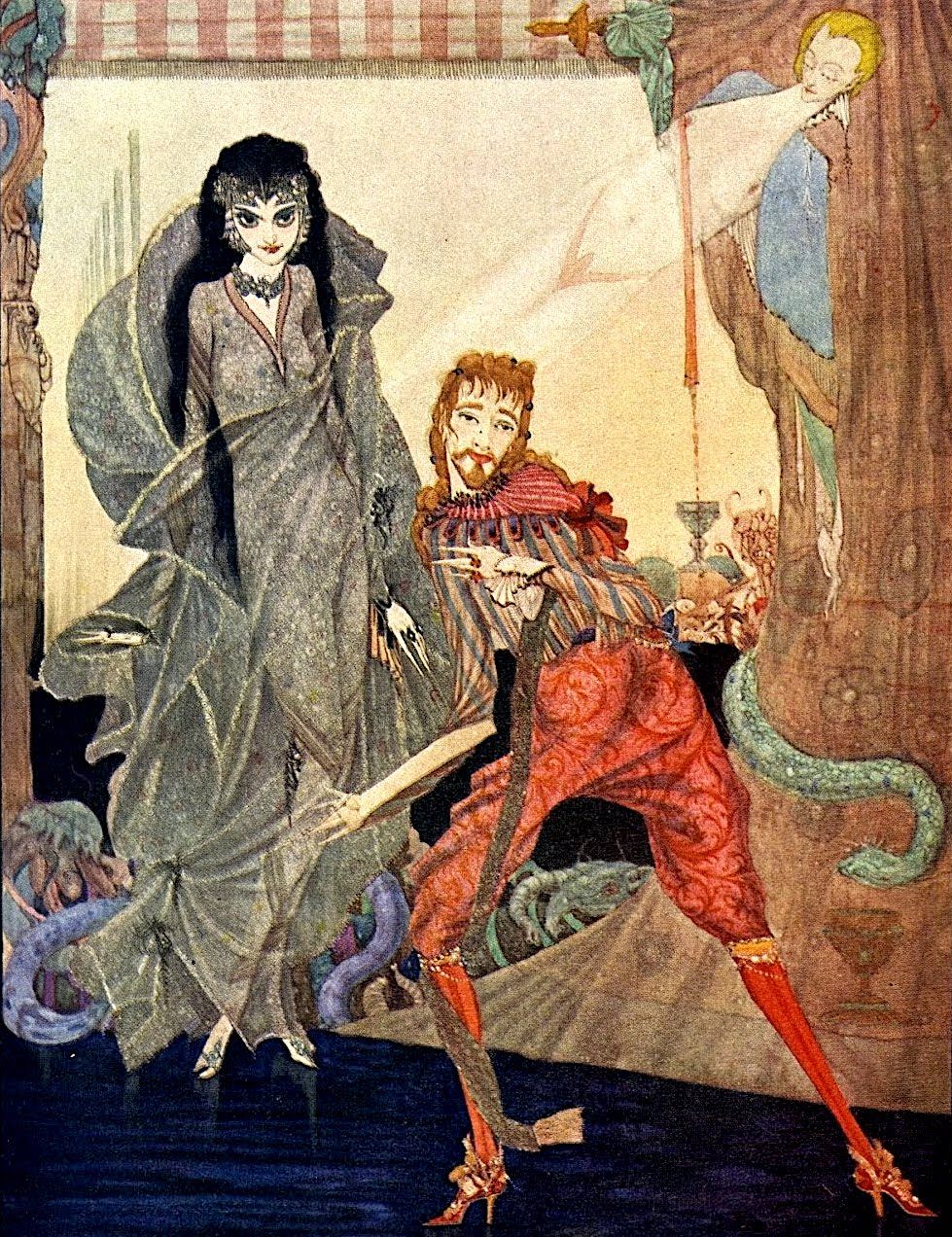

A ghost’s purpose has shifted over time, too. In Medieval times, ghosts were manifestations of cautionary tales. A woman might return as a ghost if she transgressed society’s boundaries, or committed a perceived wrong. Think, for example, of Anne Boleyn’s ghost wandering Hampton Court with her head under her arm.

Those cautionary tales cut both ways. In Medieval times, being a ghost was typically a punishment for misdeeds, real or perceived. Later, it was ghosts like the Bell Witch, rumored to have killed Bell family patriarch John Bell, doing the punishing.

“We have an innate sense of justice, we all do,” Stone says. “We like to see bad people punished and good people rewarded, however long it takes.”

For a women abused by her husband, or cast out by her community, the post-mortal realm may have been the only avenue for recompense available. Her story, relayed by women to their family members and friends, could then serve as its own kind of healing.

There’s “some kind of comfort in the fact that you can haunt someone forever if they failed to meet your needs in life,” Janes says.

Ghost stories are also a means of preserving history. For past women who may not have had the right to own property, represent themselves in court, or even keep their last names, a ghost story may be the most powerful means of being remembered.

As ghosts, women “have a staying power, they have a voice,” Hieber says.

A Female Ghost Phones Back

In San Antonio, that voice became literal in 2018, when Barrera established a hotline for San Antonio residents to call and leave messages about their encounters with the Donkey Lady. For some lucky callers, the Donkey Lady even picked up and talked back. The hotline received thousands of calls, Barrera says, and the responses revealed a community with diverse, sometimes contrasting opinions.

“The Donkey Lady received marriage proposals,” she says. “She received sweet messages. She received laughs. She received racist messages.”

The Donkey Lady’s story, as originally told, reflects some stereotypes of female ghost stories (stereotypes that are also reflected in haunted house attractions). She was seen as a spinster, an independent woman raising livestock in male-dominated ranching country who may have been marginalized by her community. Her death was gruesome, perhaps befitting her status as an outcast.

But the Donkey Lady also embodies the strength and resourcefulness of women who struck out on their own. In San Antonio, Barrera says strong, independent women are sometimes called a “burra,” which translates as something close to “Donkey Lady.”

It is perhaps that spirit of independence, more than anything else, that lent the Donkey Lady her fearsome aura.

“Is it sort of scary when a female then does not meet a cookie cutter type of identity?” Barrera says. “Is it scary when a female then has the strength?”

In San Antonio, the story of the Donkey Lady has been around for decades, the details shifting with the times. In some versions, she is ferocious, in others she is a misshapen victim, in yet others a steadfast protector. But, always, she is there.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook