How Victorian Mediums Gave Shy Ghosts a Megaphone

Spirit trumpets helped the dead speak above a whisper.

One of the biggest issues with speaking to the dead in the Victorian era—beyond the whole “being dead” thing—was that ghosts could never seem to speak loud enough. Spirits only spoke in whispers—unintelligible spectral babblings that the living human ear could barely hear, let alone decipher. A medium’s solution to this ghostly conundrum? The spirit trumpet—a fancy name for a skinny cone that supposedly amplified the voices of the dead.

Before the spirit trumpet, conversations with ghosts were restricted to more primitive, nonverbal forms of communication, according to Collectors Weekly. Spirits were known to rap on the floor or spell out words in a painfully slow manner, and mediums would speak the entire alphabet out loud until the ghosts stopped them at a certain letter. The advent of the spirit trumpet broke down these linguistic barriers by allowing the dead to speak directly with the living—kind of like a mobile phone for beyond the grave.

The spirit trumpet barged into the séance scene in the late 19th century, popularized by the spiritualist medium Jonathan Koons. In a cabin by his farm in Athens County, Ohio, Koons built a fantastical spirit room wherein guests could witness free public séances conducted by Koons and his family. As Brandon Hodge, a former magician and spirit-communication-device collector and blogger, told Collectors Weekly, Koons’s son Nahum probably invented the spirit trumpet.

According to the mediums who used these tools, the spirit could speak by possessing the vocal cords of the person speaking into the trumpet. Too soft-spoken to really project in a spirit room, the dead required all the sound-amplifying help they could get. While in use, these trumpets would supposedly float around the air, buoyed by the power of psychic energy, according to the psychic researcher William Jackson Crawford’s investigation in the 1919 collection Experiments in Physical Science.

The first spirit trumpets were homemade, either out of metal or cardboard, and resembled simple narrow cones. But as trumpets took off in popularity they became fancier, leading to steel trumpets that could extend or contract via sliding segments that slotted into one another like tubes in a jointed telescope. Some even sported glow-in-the-dark rings at the end. Everett Atwood Eckel, perhaps the best-known manufacturer of spirit trumpets, churned out the first commercialized versions from his tin shop in Anderson, Indiana.

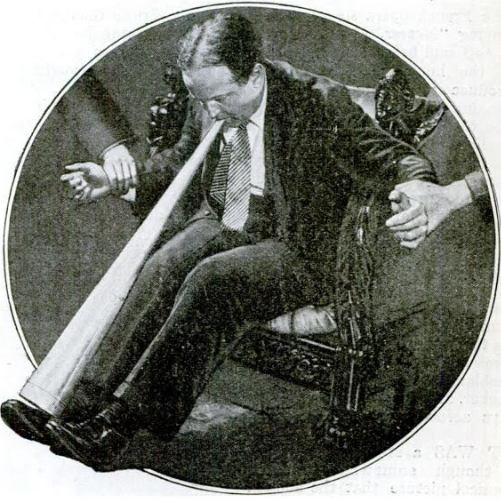

Many Victorian séances shared a predictable itinerary, Crawford wrote. First, everyone would sit down around a circle, pray, and perhaps sing a hymn—all in absolute darkness. Then the summoned spirit would rap on the floor to announce its presence, ranging from slight knocks to thunderous blows that could shake participants’ chairs. Soon after, the table would levitate and, on occasion, spin around or turn sideways. Only after this fanfare would the medium trot out the spirit trumpets. As soon as the spirit left the room, Crawford wrote, the trumpet would come crashing down.

In one séance Crawford witnessed, two spirit trumpets swooped about the room and ushered in a range of nameless voices that ordered the living guests to “sing something,” and to turn a gas lantern away from the psychic—the wish of a very private ghost, of course, and not a manipulative medium.

This story originally appeared on April 10, 2019.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook