How a Minnesota Town Fell In and Out of Love With Its Ginormous Geese

Like most human-fowl relationships, it’s complicated.

Eleanore Sutherland, a laboratory science student, used to have to stop her car in the middle of the street to clear the geese out of the way.

“They don’t react to car honks,” she says, “so you had to get out and chase them in order to get through. I’ve been bitten for trying to not run them over.”

Many cities in the United States and Canada have a problem with Canada geese. Rochester, Minnesota, however, is a town that is uniquely proud of—and plagued by—its goose population.

Best known as the home of the world-famous Mayo Clinic, Rochester is also home to a subspecies of Canada goose that was once thought to be extinct: the giant Canada goose. These birds look just like regular Canada geese, only much, much larger. In fact, a giant Canada goose can weigh up to 24 pounds and have a wingspan of more than seven feet—twice the size of a normal goose.

Normally, the narrative around extinct and endangered species is one of how mankind has made the world uninhabitable for wildlife. Rochester’s story is exactly the opposite: Its love affair with these geese was once so strong that it took a species from near extinction to omnipresent nuisance.

In its early days, Rochester was little more than a stop for stagecoach and railway travelers on their way through the Midwest. That changed in the 1880s when a tornado destroyed the town, killing 24 people and injuring 100.

Following this devastation, the local order of the Sisters of St. Francis fought to build a permanent medical facility in the region. Mother Alfred Moes approached a local physician, Dr. William Mayo, and offered to build a hospital if he and his sons would staff it. Dr. Mayo accepted, and thus changed the future of Rochester—and the international medical community. Today, Rochester is home to the top-rated hospital in the United States.

The Mayo family brought more to Rochester than just high-quality medical care. They also brought geese. In the 1920s, one of Dr. William Mayo’s sons, Dr. Charles Mayo, bought 15 Canada geese to keep on the 3,000-acre game refuge surrounding his mansion. An avid conservationist, he kept the geese for the pure enjoyment of feeding them while walking his grounds.

His flock quickly grew, attracting more than 600 geese—both giants and regular-size birds—from surrounding areas. The new population spread to Silver Lake, a 50-acre man-made reservoir in the center of town. And the Silver Lake geese soon became a staple of downtown life. Patients at the Mayo Clinic enjoyed feeding them corn during their stay. Some even bought additional geese to swell the downtown flock.

The goose population continued to grow, especially after a power plant started using Silver Lake as a heat sink in 1948. Under different circumstances, this could have been a dangerous disruption for local wildlife. But it ensured the growth and survival of the flock by preventing Silver Lake from freezing during the winter, turning it into a “goose hot tub.” Instead of migrating south each year, the Rochester geese began to overwinter at Silver Lake, protected from the harsh Minnesota climate by the power plant’s steamy discharge. By the early 1950s, more than 6,000 geese lived year-round in downtown Rochester near Silver Lake, and more joined them during each migration season.

In 1962, wildlife specialist Harold Hanson of the Illinois Natural History Survey made a surprising discovery. While conducting research on the growing Rochester goose population, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Conservation, he realized that the large geese of Silver Lake were even larger than previously thought. They were so heavy, in fact, that the scientists were convinced that the scales they used to weigh the birds were broken. After buying bags of flour and sugar at a local grocery store to verify their weight, they realized that the scales were indeed correct.

And so the world learned that Rochester’s geese were actually Branta canadensis maxima—a giant subspecies of the Canada goose thought to have been extinct for more than three decades.

To make sure that they stayed not extinct, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources put strict hunting protections in place for the birds in Rochester. At the same time, it launched a national revitalization effort, transplanting giant Canada geese from the Midwest to protected locations on the East Coast.

The goose population in Rochester immediately skyrocketed. At its peak, in 2005, there were nearly 40,000 of the giant birds on the balmy waters of Silver Lake—compared with a human population in Rochester of less than 100,000—and their honking could be heard for miles.

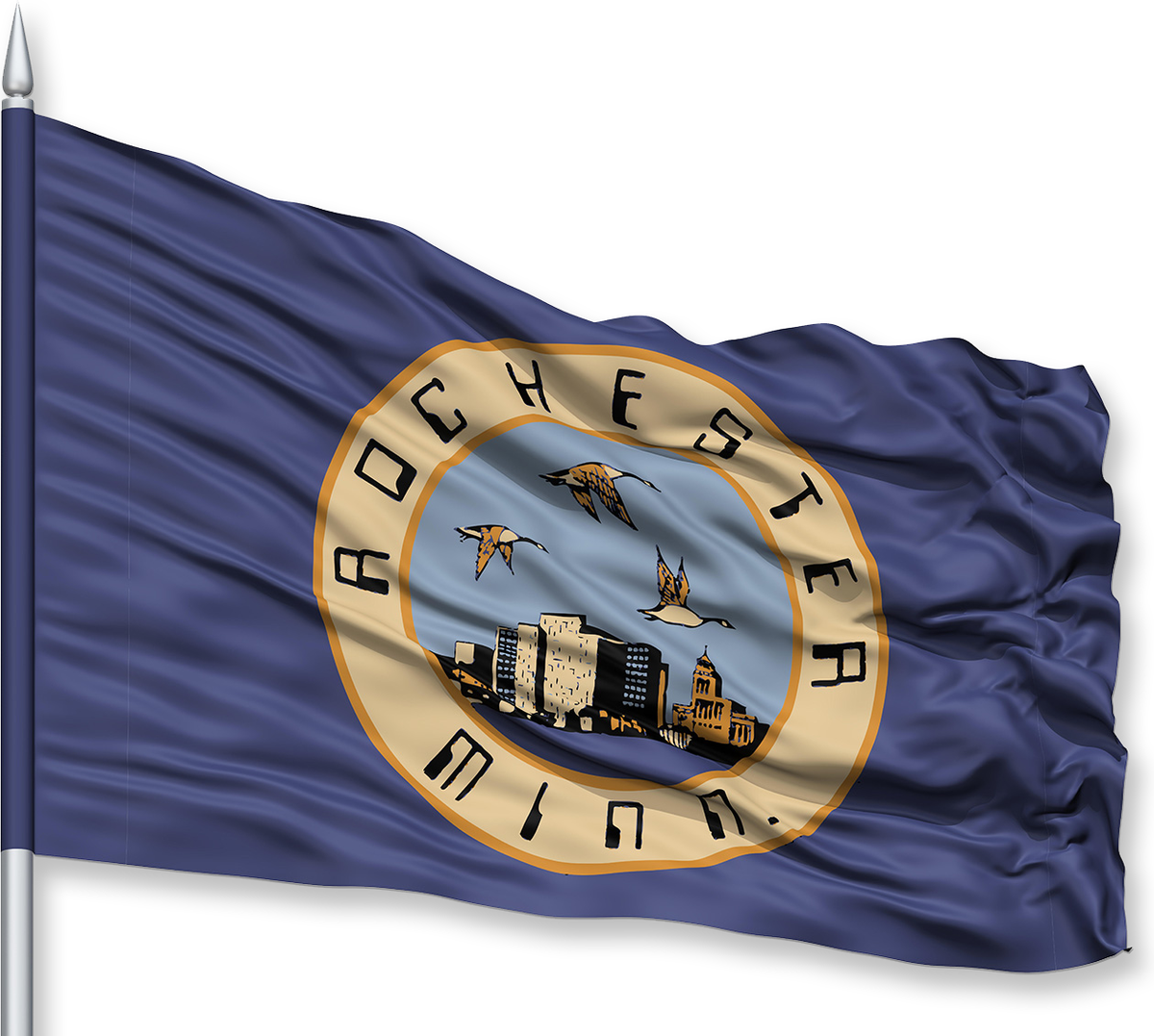

Not that many people complained. Rochesterites loved the geese, and the geese loved Rochester. The warm water and unrestricted habitat were an avian paradise. The geese became the city’s symbol, both officially and unofficially. Feeding them was a common pastime for residents and visitors alike. The birds’ image was emblazoned on parking garages, dental offices, and restaurants. In 1980, the city council adopted a new city flag design that prominently featured three giant Canada geese flying above the Rochester skyline. Goose statues decorated by local artists were put up throughout the city, creating prime photo opportunities.

But as both the human and goose populations continued to grow, their coexistence grew tense. After a decades-long feeding program that had begun in the 1930s, the geese were comfortable with humans—some would say too comfortable—and felt empowered to harass anyone in their path, expecting, and sometimes demanding, to be fed.

“When I was a young kid, I saw a one-footed goose at Goose Poop Park [aka Silver Lake Park],” says Sophie Goodner, 25. “I thought it looked lonely, so I went over to feed it. It saw the food in my hand and charged at me. I saw that one-footed monster several other times, and it charged me every single time.”

Bryan Mullen, a former Mayo Clinic nurse who lived in Rochester in the 2000s, recalls being afraid to go onto the patio of his condo because of the geese. “There were always two or three of them hanging around on the patio, honking at our window. I didn’t want to mess with them.”

But the goose chases and intimidations paled in comparison to the complaints about what the geese left behind. A regular Canada goose can produce up to three pounds of fecal matter a day. With tens of thousands of giant geese living on Silver Lake, many public areas in downtown Rochester became unusable. By 2002, nearly all of the waterways surrounding the lake were contaminated with goose fecal matter.

Nevertheless, Rochester’s humans and geese coexisted in a mostly peaceful manner—until 2006, when a potential avian influenza (H5N1) outbreak gripped the city and panicked its residents. The virus was first detected in geese in China, and countries throughout Asia that year were reporting a growing number of human fatalities from H5N1 outbreaks.

While there were no reported cases in the United States at the time—including Rochester—some alarmists considered an outbreak inevitable. Faced with the possibility that one could potentially occur right next to the Mayo Clinic’s large population of medically fragile patients, the city decided that it had to act to control the goose population.

But residents were divided on how best to address this potential threat. Some advocated lethal measures, including expanding the early season hunting and oiling goose eggs to prevent embryonic development. Many others, however, advocated on behalf of the geese.

Tensions ran high, and the city held two contentious open Goose Population Control Meetings to discuss options. During one of these meetings, resident Amy King—one of many attendees vehemently opposed to lethal measures—decried the extreme proposals as “cold-hearted and barbaric.”

After much debate, the city chose to protect the geese by making Silver Lake less inviting. In 2007, officials placed vegetation buffers—composed of prairie grasses and wetland plants—to deter nesting along the shoreline, and removed the goose feeding stations that ringed the lake. The following year, the coal-burning power plant that prevented Silver Lake from freezing shut down.

In the years since, Rochester’s resident goose population has plummeted. According to recent tallies by the Zumbro Valley Audubon society, there are now a mere 10,000 geese at Silver Lake.

Giant Canada geese are still a fixture in Rochester. The Canadian Honker remains a favorite restaurant, and the local amateur baseball team is still called the Rochester Honkers.

“Everyone [from Rochester] has such strong feelings about geese that one mention completely throws the conversation [in] that direction,” says Danny Luedkte, a former resident now living in Vermont. “I miss people from Rochester. No one else gets it.”

But as the goose population has dwindled, the city’s obsession with the giant birds has lessened. “With fewer geese around, there are fewer goose-and-human encounters,” says Dan Eckberg, a geographic information systems planner. “When I was a kid, everyone had a story about being chased by the geese. It’s just not the same anymore.”

In 2018 the city considered new designs for its municipal flag. Two of three three finalists did not feature any geese whatsoever.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook