A Ruined French City, Resuscitated In a Garden

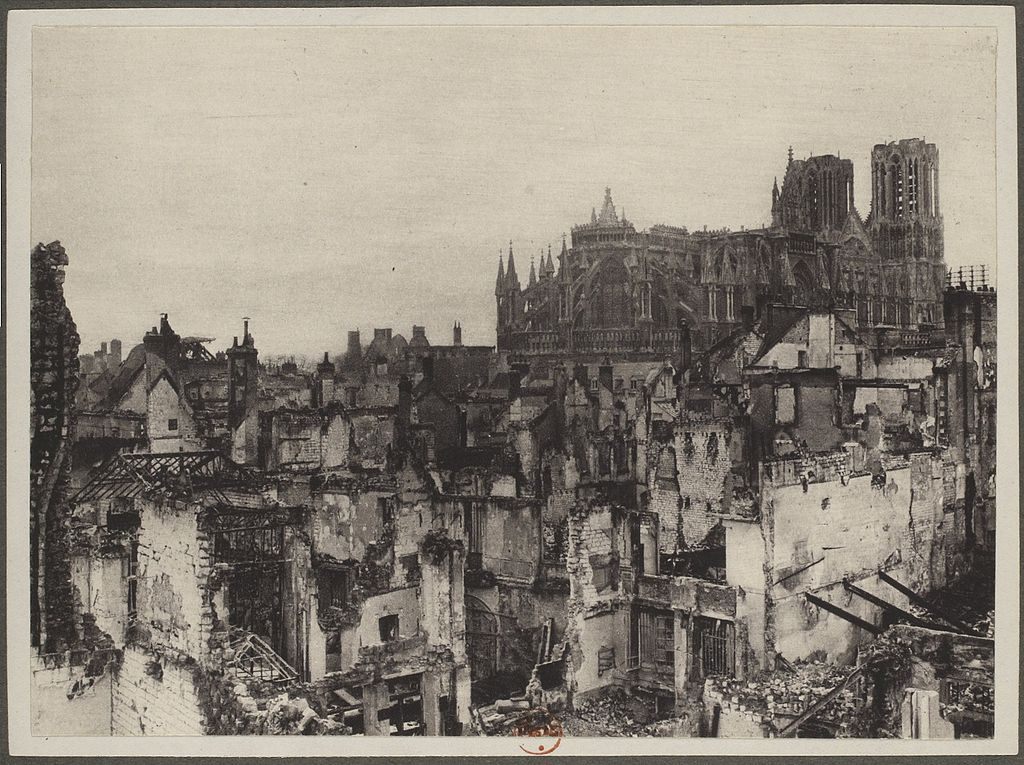

The city of Reims, c. 1916. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The city of Reims, c. 1916. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In the ancient French city of Reims there is a magnificent turreted town house that dates from the 13th century. It is surrounded by a light-colored wall with a large plaque commemorating the time when 17-year-old Joan of Arc brought Charles VII to Reims to be crowned in 1429.

But hidden behind the wall is something extraordinary: a rarely visited garden filled with architectural ruins and flowerbeds of wild roses. Collected by one man following the armistice of 1918, this haunting graveyard of forgotten doorways, columns, and archways tells the story of one France’s most historic cities, and its almost complete destruction during World War I.

Located in the bucolic Champagne-Ardennes region of northeastern France, Reims has been the traditional crowning site of the kings of France since the 11th century. The old city is dominated by the 800-year-old cathedral of Notre-Dame de Reims and the Romanesque Saint Remi Basilica, while the countryside is dotted with the vineyards of prestigious champagne houses, like Veuve Clicquot, that go back hundreds of years.

The restored Hotel le Vergeur and the ruined le Pavillon Coquebert. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The restored Hotel le Vergeur and the ruined le Pavillon Coquebert. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

As the German army poured through Belgium and into France in the autumn of 1914, Reims became a key strategic target–both tactically, as it was a gateway to Paris, about 80 miles away, and in terms of French morale. The city was swiftly captured just a month after war had been declared, although the Germans only occupied the city for eight days, until the Allied victory at the Marne forced them to withdraw.

The massed German army promptly took up a new position on the ridges of the champagne vineyards a few miles to the north east of the city, where as part of their giant western front trench system, they would stay until near the end of the war.

Unable to recapture Reims, the Germans decided to reduce it to ruins. For four years, the German artillery pulverized the ancient city, all but obliterating it. High explosives and incendiary shells rained upon the city almost continually, as fires engulfed the city. On April 1st, 1917 alone, over 2,800 shells exploded on Reims. The next night, a further 2,100 shells fell on the city.

Reims had once been the traditional crowning site of French Kings. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Reims had once been the traditional crowning site of French Kings. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Incredibly, the citizens of Reims largely refused to leave their besieged home. Most sought safety in the caves buried hundreds of feet deep underneath the Pommery champagne house.

By the end of the war, 80 percent of the city where French kings had been crowned for nearly a thousand years had disappeared. Of the city’s 14,000 buildings, only about 5,000 remained, including large parts of the Cathedral, which the Germans purposely spared. Reims was the hardest-hit large city in France. In 1919, the President of the French Republic conferred the Legion of Honor upon the whole town, dedicated to the “martyred city, destroyed by an infuriated enemy, powerless to hold it.”

Faced with the giant task of rebuilding the city virtually from scratch, hundreds of architects were invited to Reims, and given nearly free reign to redesign the ruined city. Some 6,500 new buildings were constructed during the 1920s, mostly in the Art Deco style. Visitors walking along the boulevards today will see important civic buildings in a diverse array of modernist styles.

But centuries of French building history would have been all but lost in the rubble, but for the efforts of one man.

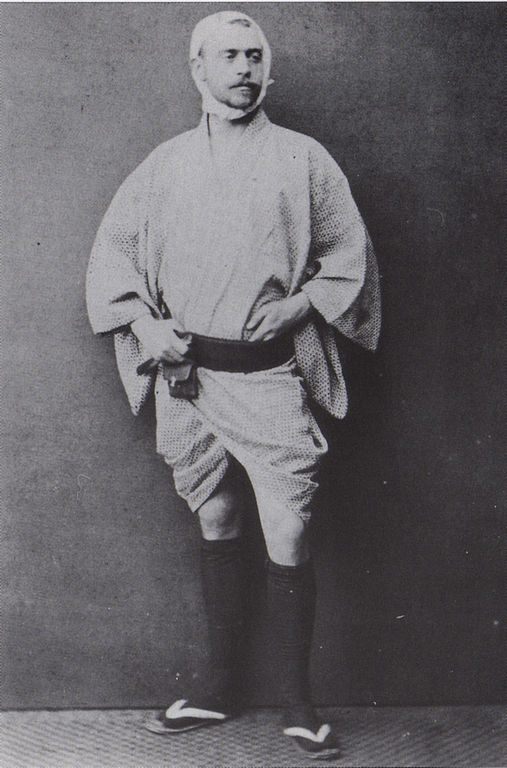

Hugues Krafft in 1882. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Hugues Krafft in 1882. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Hugues Krafft was born in Paris to a German father in 1853, but moved to Reims in the late 19th century to work in the lucrative champagne trade. Looking to buy a suitably grand home, he purchased an old town house, called the Hotel le Vergeur, which overlooked the old market square, where linens, wheat and champagne had been traded for centuries.

The turreted home was severely damaged in World War I. In the 1920s, Krafft restored most of the townhouse to its original beauty, but left one wrecked section standing. That is the Pavilion Coquebert. The crumbling masonry and blasted architecture of the Pavilion, which dates to the 17th century, gives a poignant glimpse into how the rest of the devastated city would have looked in 1918.

The Hotel le Vergeur where Hugues Krafft built his garden of rescued ruins. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The Hotel le Vergeur where Hugues Krafft built his garden of rescued ruins. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

As the ruins of Reims were torn down to make way for new construction, Krafft searched through the rubble for the remnants of the city’s historic past. He saved doorways, lintels, whole facades, columns, archways and tombs and brought them to the garden of the Hotel le Vergeur, where he created his garden of ruins. For the interior of the hotel, he salvaged fireplaces, libraries and artwork.

Following his death in 1935, he left the collection to the Societe des Amis du Vieux Reims, where it still rests today.

Preserved ruins of Le Pavillon Coquebert, destroyed during World War I. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Preserved ruins of Le Pavillon Coquebert, destroyed during World War I. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Ancien Hotel Lagoille de Courtagnon

Dating from the end of the 17th century, Krafft rescued part of a wall from this old hotel, along with a remaining archway. According to a plaque at the site, it was from this wrought iron balcony that Marie Antoinette watched her husband Louis XVI leave Notre Dame cathedral to go to the Abbey Saint-Remi to touch sufferers from tuberculosis.

Balcony from l’ancien Hotel Lagoille de Courtagnon. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Balcony from l’ancien Hotel Lagoille de Courtagnon. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Facade du 5 rue de Sedan

This entire facade came from a majestic town house, built just behind the city hall.

Facade du 5 rue de Sedan. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Facade du 5 rue de Sedan. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Portail de l’Ancienne Abbaye de Saint-Pierre-les-Dames

This beautiful entrance Krafft saved from an old Benedictine monastery that dated from the 6th century, which was all but completely destroyed by German artillery.

Portail de l’Ancienne Abbaye de Saint-Pierre-les-Dames. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Portail de l’Ancienne Abbaye de Saint-Pierre-les-Dames. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Portail de l’Ancien Hopital Saint-Marcoul

Dating from around 1650, this hospital was the domain of a monk called Saint Marcoul, who it was said could cure scrofula, or tuberculosis of the neck with his touch. When the Kings of France were crowned at the cathedral, the tradition became that they would visit Saint Marcoul to lay hands on the afflicted. Krafft rescued the entire giant entrance, including a doorway still inscribed Hopital de Saint Marcoul.

Portail de l’Ancien Hopital Saint-Marcoul. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Portail de l’Ancien Hopital Saint-Marcoul. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Portail du Cloitre de l’Ancienne Eglise de Saint Pierre le Vieil

Once one of the largest churches in Reims, the structure was originally demolished during the French Revolution. According to a plaque at the site, the door was uncovered during the digging of the front line trenches at Reims, and eventually saved by Krafft.

Portail du Cloitre de l’Ancienne Eglise de Saint Pierre le Vieil. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Portail du Cloitre de l’Ancienne Eglise de Saint Pierre le Vieil. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

16th century tomb of a Knight of Malta

This tombstone marked the burial place of a Knight of Malta, also known as the Knights Hospitaller, of the Order of Saint John. The legendary military order was charged with the defense of the Holy Lands and the Crusades, and is one of the last Orders from the Middle Ages which is still active today.

16th century tomb of a Knight of Malta. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

16th century tomb of a Knight of Malta. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Arcaded Romanes de l’Ancienne Commanderie du Temple

This giant stone archway in the Romanesque style originally adorned a commandery of the Knights Templar. It had been given to the legendary order by Archbishop Henry of France. For nearly two centuries, the Knights Templar grew in power and stature, until on Friday, October 13th, 1307, all the Knights Templars were rounded up by Philip IV, and their property seized, including this building.

The order was disbanded by the Pope five years later, whereupon the building became the property of the Hospitaller Order of St. John, who held it until the days of the French revolution. According to a plaque, the once beautiful building was eventually purchased by Madame Clicquot Ponsardin, of the Veuve Clicquot champagne family, in 1831. The archway was found during the excavations following the end of the war by Krafft and brought to his garden.

Arcaded Romanes de l’Ancienne Commanderie du Temple. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Arcaded Romanes de l’Ancienne Commanderie du Temple. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Walking through the beautiful, and often deserted gardens of the Hotel le Vergeur is a similar experience to visiting an empty historic cemetery. Covered in ivy and still bearing the scars of endless shrapnel and artillery fire, the carefully collected architectural ruins speak to the four years of horror as the German shelling gradually destroyed the ancient city.

Today Reims, with its historic cathedral surrounded by luxurious champagne houses and vineyards, is once again a bustling tourist destination. Walking through the city it is hard to imagine that nearly everything you see is not even a century old. That is, unless you venture into the walled garden of the Hotel le Vergeur, and stroll through the scattered ruins of the lost city.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook