The Prima Donna Who Snuck into Tibet in 1912 to Meet the Dalai Lama

Alexandra David-Néel, in Tibet 1933. (CC BY 2.0, Preus Museum)

This is the second part of a five-part series about early female explorers. The first part can be found here.

The first western woman to gain an audience with the Dalai Lama, the Belgian-French Buddhist scholar Alexandra David-Néel is best known for her forbidden journey to Lhasa, when, aged 55, she ascended the Tibetan steppes on a trek that saw her so malnourished she had to eat the leather from her boots to stay alive.

From the age of two, David-Néel was wandering away from her parents in the streets of Paris, where she was born in 1868. Aged 18, she cycled solo from Brussels to Spain without telling her family. This was 1886 — a time when the roads were dirt and women were expected to be accompanied for even the simplest excursions.

And that was just the beginning.

David-Néel as a young woman, in 1866. (Public domain)

David-Néel as a young woman, in 1866. (Public domain)

Having blown her inheritance on a trip to India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) while a student of eastern religions at the Sorbonne, in her twenties David-Néel traveled across Asia and North Africa as prima donna with the Hanoi Opera Company. When her voice began to falter, rather than be mediocre, she left to become the director of the Tunis Casino. It was here that she met and wed, at age 36, the wealthy railroad executive Philip ‘Mouchy’ Néel.

Falling in love didn’t stop her. In 1911 she went back to India, and later became the disciple of a Buddhist monk, the Gomchen of Lachen, living and meditating in a Sikkim cave on the border with Tibet for three solid years — a controversial move indeed.

“The earth is the inheritance of man, and consequently any honest traveler has the right to walk as he chooses, all over that globe which is his,” she wrote in My Journey to Lhasa in 1927.

Tibet, 1937. (Bundesarchiv Bild, CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Tibet, 1937. (Bundesarchiv Bild, CC-BY-SA 3.0)

While it was acceptable, even fashionable, to study comparative religion from a distance, to actively don the orange robes, particularly as a woman, was scandalous at the time when the only acceptable costume for European women in the Orient was a long-sleeved white dress, white gloves, broad-brimmed hat, and — of course — a lacy parasol. But David-Néel didn’t possess the sense of cultural or national superiority that such an outfit conveyed. She traveled to listen and learn.

David-Néel had promised Mouchy that she wouldn’t be gone for too long, but she had already been in India for years by the time British forces expelled her in 1916, for “trespassing” into Tibet, which was forbidden. It was the height of WWI and she was unable to return to Europe, or Tunis. Instead she went further east, studying at the monasteries of Korea and Japan with the 15 year-old Aphur Yongden, a perceptive Sikkimese lama who would become her lifelong companion and adopted son.

Yongden, Tibet, 1933. (Elizabeth Meyer, CC-BY-2.0)

Yongden, Tibet, 1933. (Elizabeth Meyer, CC-BY-2.0)

Finding Japan too tame for their tastes, David-Néel and Yongden took the dangerous journey east to west across the Chinese empire, covering 5,000 miles by mule, yak, horse, and foot while the country was collapsing into civil war.

They saw murders and battles, had to barter for passage with warlords and despots, and, on reaching the border with Tibet in the winter of 1923, it was time for their most challenging journey of all: Disguised as Tibetan pilgrims, the two of them set out for Lhasa while the country was still off-limits to foreigners. Each morning, David-Néel dyed her reddish brown hair with Chinese ink, weaving in a scrubby yak’s tail for added effect.

A middle-aged “little round ball,” David-Néel ventured where no European had gone before, trekking through the rumored “cannibal country” of the Po people and across a frozen 19,000-foot mountain pass in the dead of winter.

That year, the woman who had grown up in luxury in Paris and Brussels savored a Christmas meal of leather boot strips soaked in boiling water. It was all the sustenance she and Yongden had.

Potala Palace (Flickr user reurinkjan, CC-BY-2.0)

Potala Palace (Flickr user reurinkjan, CC-BY-2.0)

Four months into their treacherous journey, David-Néel and Yongden arrived in the holy city of Lhasa. On seeing Potala Palace, the winter palace of the Dalai Lama since the 7th century and the highest ancient palace in the world, she wrote that “golden roofs glittered in the blue sky, sparks seeming to spring from their sharp upturned corners, as if the whole castle, the glory of Tibet, had been crowned with flames.”

Remaining disguised, she and Yongden stayed in Lhasa two months, until they were eventually discovered and sent packing by the British. She returned to France in 1928, and published her most famous work, Magic and Mystery in Tibet, that next year. However, she never stopped her study of Tibet. In 1937, David-Néel Yongden traveled through the Soviet Union to reach Tibet, where they stayed for a time in the eastern highlands, and circumambulated the holy mountain of Amnye Machen.

Alexandra died in 1969 just before her 101th birthday at her home in Digne, Provence. Her ashes were mixed with Yongden’s, and scattered in the Ganges at Varanasi, as was her request.

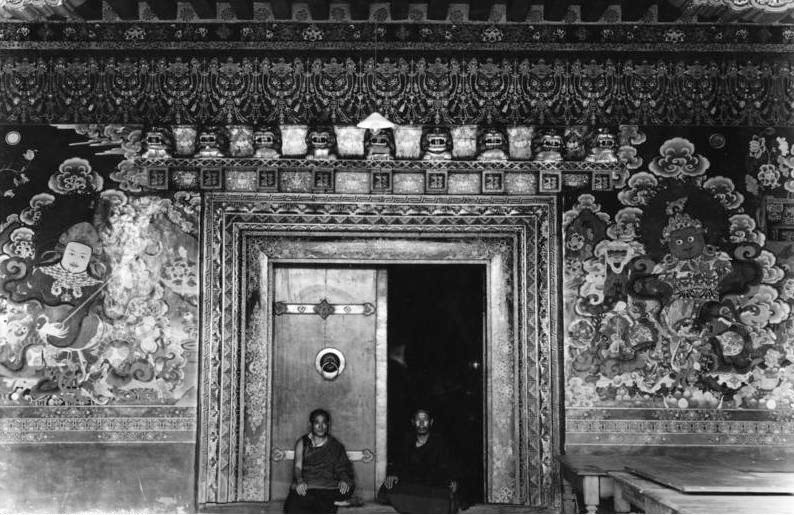

Alexandra David-Néel, in Tibet 1933. (CC BY 2.0, Preus Museum)

Alexandra David-Néel, in Tibet 1933. (CC BY 2.0, Preus Museum)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook