Why All Beer Once Tasted Like Smoke

Those were the days.

Today’s brewers can add any number of flavors to their beers. Some are newfangled, such as chili pepper or pumpkin; others are deeply traditional. Smoke is one of the latter, with a long and widespread pedigree. All across Europe, a hint of barbecue was once pervasive—until the Industrial Revolution, the flavor was the inevitable result of the brewing process. Malt is one of beer’s primary ingredients, and a change in how it’s made brought beer out of its smoky past.

Grains, unlike wine grapes and cider apples, don’t contain sugars. They have starches, which can’t be fermented until they are accessed and converted into sugars. Malting is the process of accessing those starches by steeping the grains in water.

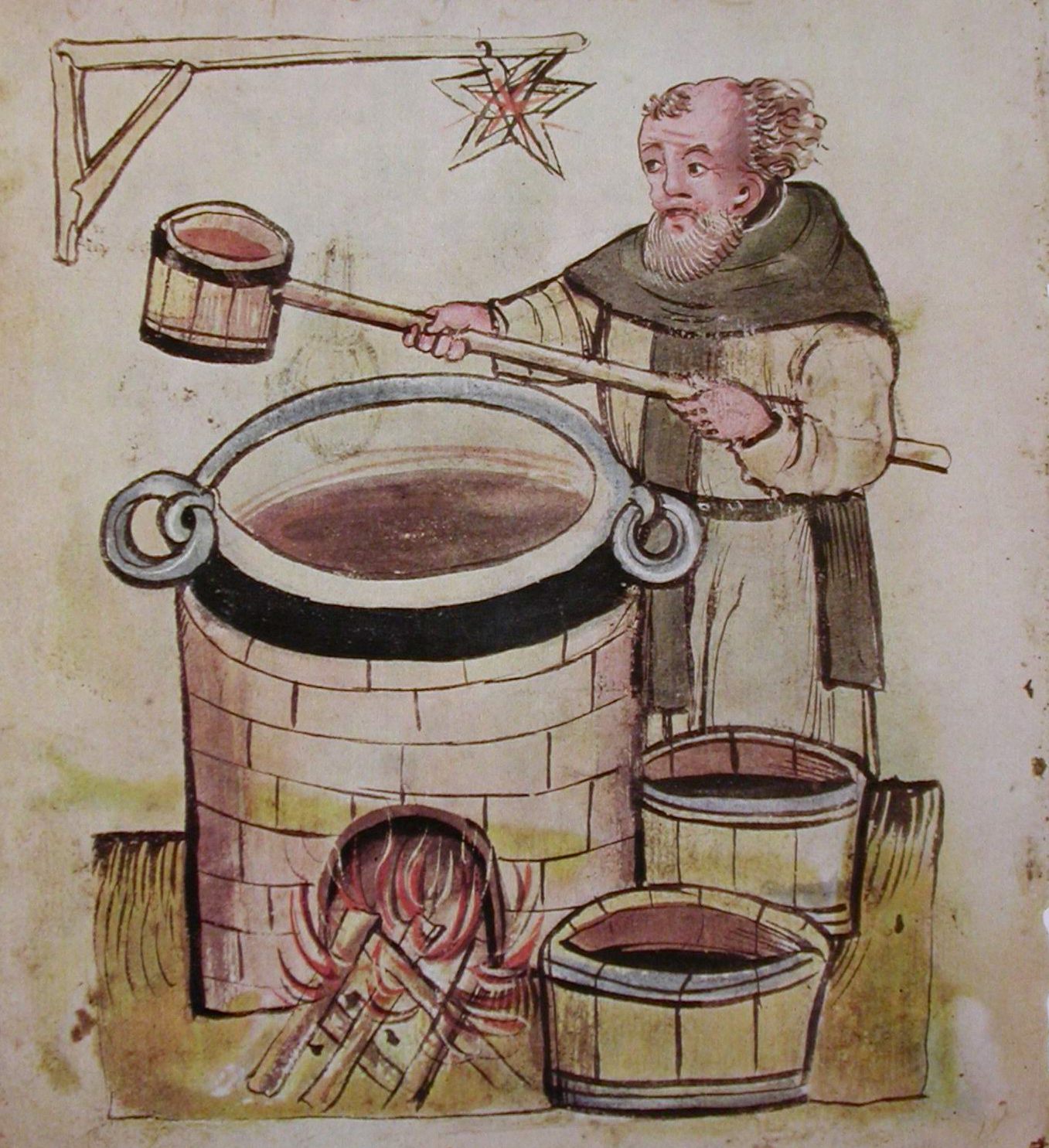

Malting makes the grains begin to sprout, but this process must be stopped by drying the grains before they mold. In most of Europe’s beer-producing countries, a fire was the only way to do this. “Basically you’d have a firebox below and either a fine screen or something of that sort, on top of which was a bed five or six inches deep of sprouted malt,” says Garrett Oliver, Brewmaster at Brooklyn Brewery and author of The Brewmaster’s Table. Hot air, and with it, smoke, rose up through the malt, drying it and imbuing it with a smoky flavor.

Change came from England, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Over the course of the 17th century, cheap, efficient coal came into use, which gave maltsters the opportunity to jigger their process. Coal gave them a more even, controllable temperature than wooden fires. But coal smoke may not have been as pleasant as wood-fired smoke. Once they began using coal, Oliver says, the English could use heat exchangers that took consistent, well-regulated hot air to the malt and directed the smoke away and up through a chimney. As a result, smokiness was no longer a default component for beers.

Pulling back the curtain of smoke meant beer drinkers could enjoy the cleaner, crisper flavors of malt and hops. The “new” beers were also lighter and more consistent in their color; beers made with smoked malt would vary in their color and flavor depending on how much wood was used, how seasoned the wood was, and ambient temperatures. Oliver says that while the smoky beers might have been flavorful, they generally wouldn’t have been “refreshing” in the way beers made with unsmoked malt were.

Refreshment isn’t the only reason to drink beer, of course, and some beer drinkers didn’t want to give up their smoky brews. Certain areas in Norway and Poland clung to a smoky style. Grodziskie, a smoked Polish wheat beer, persisted until the 1930s, and has been resurrected by some American craft breweries. Homebrewers in Norway shared communal malting houses using the old, smoky malting process until the 1970s. Homebrewer John Morten Granås resurrected the traditional malt house a few decades ago, and now the Stjørdal area east of Trondheim is home to a few dozen.

Commercially, only in Bamberg, Germany, have several brewpubs persisted in making smoke beers (Rauchbier, in German) since the Middle Ages. Much of the move to pale, smoke-free malts was tied up with industrialization, and bucolic Bamberg, in the heart of Franconia (the northern part of Bavaria), missed out.

“Bamberg is, by German standards, far away from any industrialized areas,” says Matthias Trum, the sixth generation brewmaster and owner of Aecht Schlenkerla. “We never had much industrialization here, especially no coal or steel industry. Coal was somewhat hard to acquire here, and it was easier for brewers to stick with wood as fuel.”

To continue making Rauchbier, Aecht Schlenkerla and Spezial, a competitor across town, make their own malt in-house. This had been the norm, but coal-firing meant malting could be done at a much larger scale, making it more affordable for most breweries to outsource it. Both breweries use wood from local beech trees, although Aecht Schlenkerla recently introduced an oak-smoked beer, which has a softer, sweeter smoke character. The disappearance of smoky beers in other places means the variety of characters imparted by local woods was lost as well. Grodziskie was made with oak; in Norway, alder and birch was the norm. Many Scotch whisky distilleries used and still use peat, which puts its stamp on their whiskies in just the same way as different woods do on these beers.

With such a small set of examples to draw from, it’s hard to know how modern, smoky beers compare to those of the pre-industrial past. Trum says that Aecht Schlenkerla brewers have held closely to the old ways, and he isn’t convinced that the “new” smoked beers shed much light on history, enjoyable though they may be. “Today’s craft breweries’ smoked beers use industrially made and smoke-flavored malt, so it’s not the traditional way of doing it. They are likely to be further away from the original flavor.”

In any case, smoke may be due for a comeback. “I think of smoke as one of the primary characteristics of human food,” says Oliver, one which distinguishes our diet from that of animals. He argues that, with millenia of open-fire cooking behind us, smoke has a primal appeal that almost every human has enjoyed. Technology may have removed smoke from beer, but that doesn’t mean we don’t miss it. “I think that there is an interest in getting back these dimensions of food and drink that have been lost and can be really pleasant.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook