The First Woman to Drive Around the World Wore Men’s Breeches and Had a Pet Monkey

Aloha Wanderwell was the Amelia Earhart of the automobile.

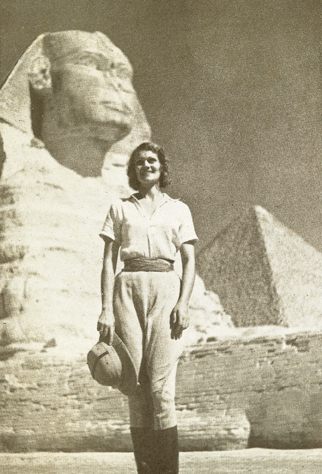

An 18-year-old woman dressed in men’s riding breeches and a scout’s cap lay restless at the foot of the Great Sphinx in Egypt. It was 1924, just two years after archeologist Howard Carter opened the tomb of Tutankhamun. “I could not bear to sleep,” the woman wrote in her memoir, Call to Adventure. “I sat on a sand dune and watched the full moon sail in a sky that was like an upturned goblet of dark, blue glass… There were trillions of stars, and not far away I could see the outline of the Sphinx, smiling and sightless.”

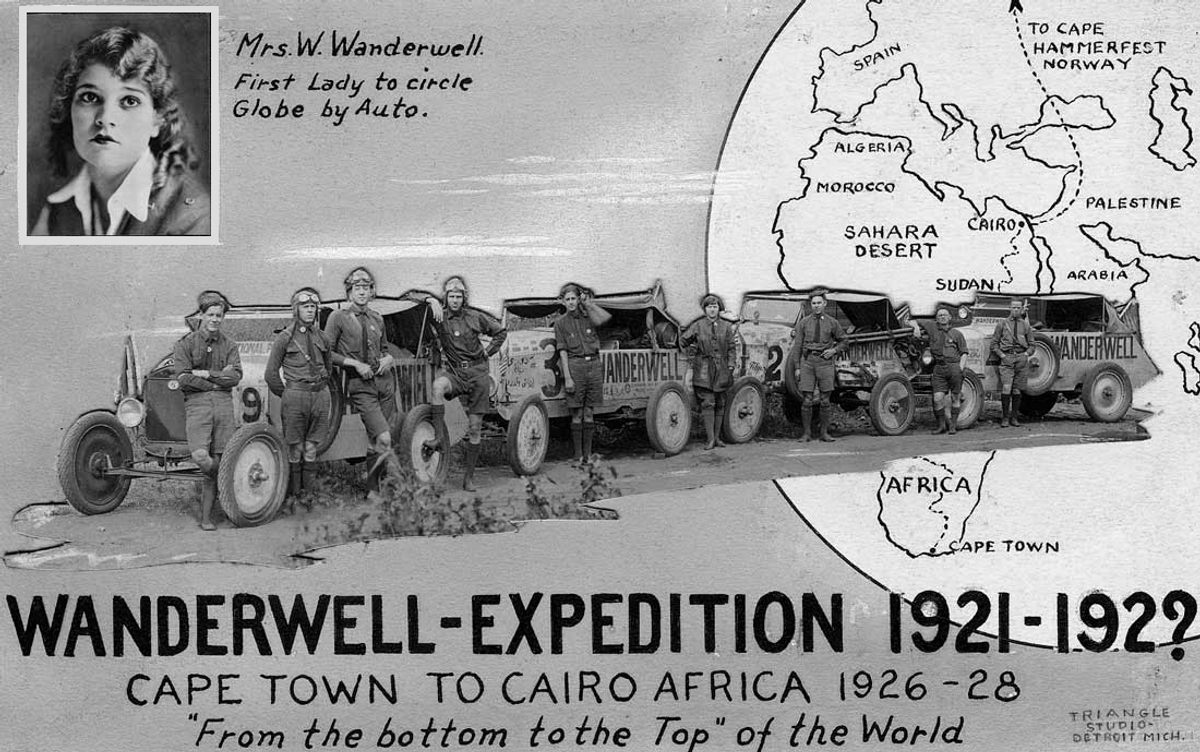

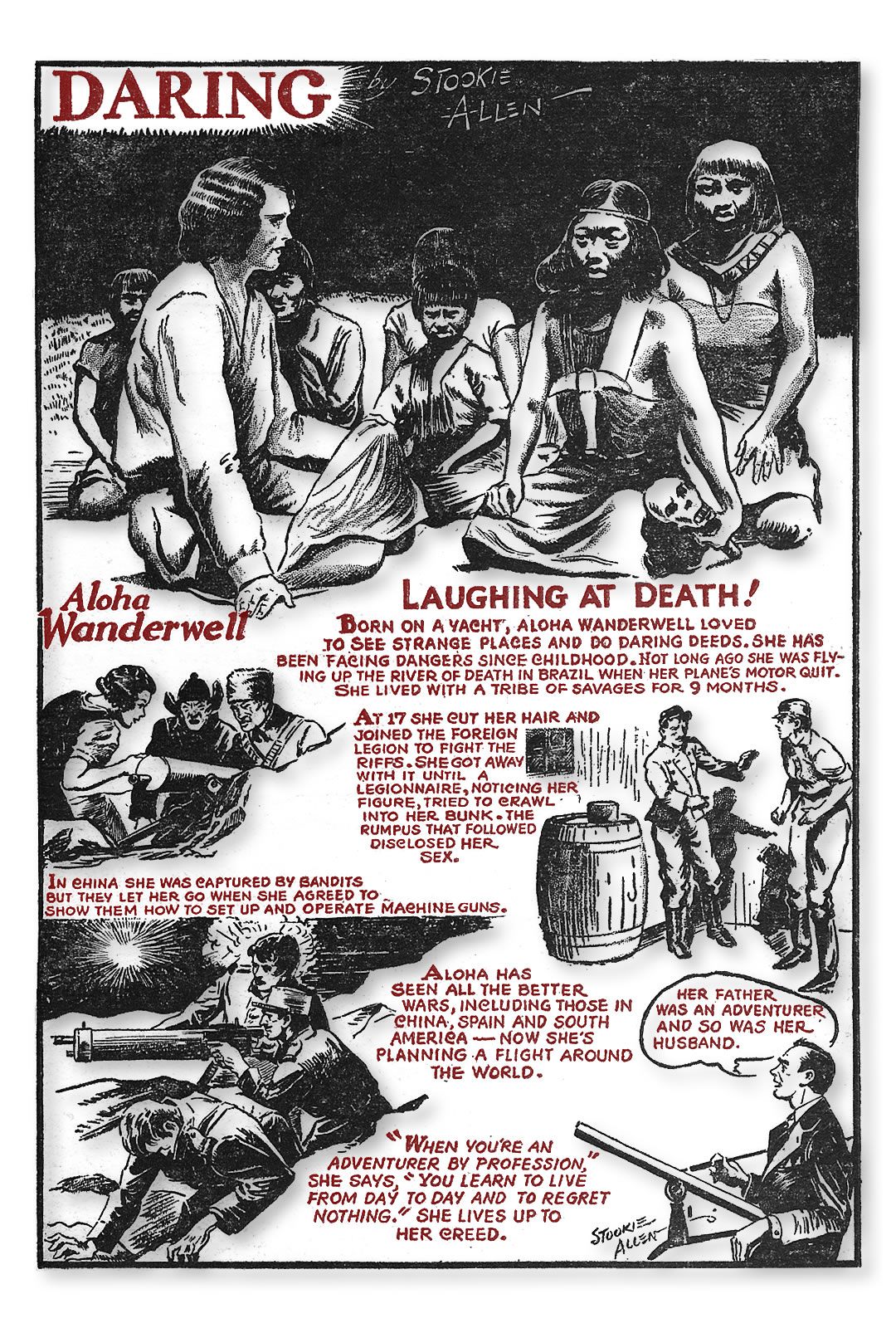

This was one of many adventures that Aloha Wanderwell, recorded during her seven-year automobile expedition around the world. Newspaper headlines deemed her the “World’s Most Widely Traveled Girl,” “The Amelia Earhart of the Automobile,” and “The First Woman to Drive Around the World in an Automobile.”

In 1922, Wanderwell joined a race to visit the most countries in the world alongside a former Polish seafarer, who went by the stage name “Captain” Walter Wanderwell, a camera crew, and a monkey named Chango. Traveling in a small caravan of Model T Fords, she trekked through 43 countries and four continents, journeying through battlefields in France, living with Indigenous people in Borneo, and disguising herself as a man to sneak into Mecca and pray. Wanderwell, who served as a cinematographer, photographer, translator, driver, actress, and seamstress, filmed and wrote detailed descriptions of parts of the world that hadn’t been documented yet. Her publicized adventures around the world skyrocketed Wanderwell to fame throughout the 1920s and 1930s, but much of her life remains a mystery today.

“Aloha Wanderwell has been a secret for many, many years,” says Richard Diamond, Wanderwell’s grandson. Diamond archived Wanderwell’s life online, curating all the photographs and films she took during her travels.

Wanderwell was born Idris Galcia Hall in Winnipeg, Canada. She was a self-described independent tomboy who often rebelled against her teachers at the convent school she attended in France. If her ambitious personality didn’t turn heads, her 6-foot-tall stature, blonde hair, and movie star looks were a rare sight, writes Tracy Landecker in an essay that proceeds Wanderwell’s memoir, Aloha Wanderwell: Call to Adventure. When her father was killed in combat during World War I, Wanderwell wanted to assume the role of the head of the household. She wrote in her 1939 memoir: “I ached for action, but I did not know in which direction to go. I had already bothered my mother on the subject of my earning money. I wanted a career and I wanted to become the man of the family.”

At the young age of 16, she came across an ad for the Wanderwell Expedition in the Paris Herald that read, “Brains, Beauty & Breeches — World Tour Offer For Lucky Young Woman…. Wanted to join an expedition…Asia, Africa.”

#HappyEaster pic.twitter.com/eCrG4b52sZ

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) March 27, 2016

Valerian Johannes Piecynski, who took on the name Captain or “Cap” Walter Wanderwell, started the Wanderwell Expedition under his Work Around the World Educational Club in 1919 after the end of World War I. Originally, he and his former wife began the “million dollar wager endurance race” to help restore international travel and promote the League of Nations. The entire expedition was funded by souvenir pamphlets, speaking engagements, and screenings of the footage collected on the road. However, when Cap and his wife split, a spot opened up for a new secretary and driver.

1924 Japan, Walter and Aloha saluting. As a young boy Walter loved the scouts hence the uniform and 3 finger salute pic.twitter.com/BMpGYMUVJc

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) May 6, 2016

Wanderwell, who was fluent in French, Spanish, Italian, and spoke some Russian, Chinese, and Japanese, was perfect for the role and landed the job. When she joined the expedition in 1922, Cap gave Idris Galcia Hall her stage name, and she became Aloha Wanderwell. “We were off!” she wrote. “The whole world was out there. I reaching for it, the world reaching for me—ecstasy—the ravishing thrill.”

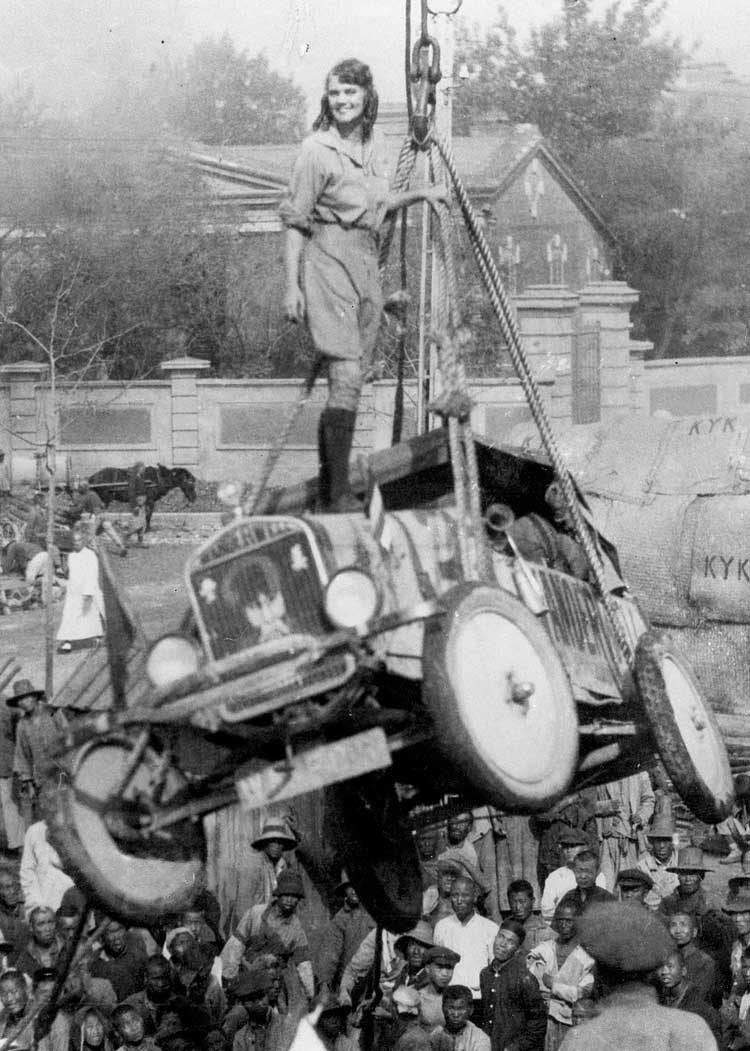

Although she began as a secretary and assistant, she quickly became both the star and director of the films taken throughout the expedition. Wanderwell was in charge of Unit 2, the Model T Ford nicknamed Little Lizzie, which endured a lot of hardships throughout the expedition. But the Model T Fords were picked specifically for this trip.

“This adventure epitomizes the durability of the Model T Ford and demonstrates the bravery of a pair of adventurers who helped forge the early days of romantic motorized exploration,” Dan Treace, a preserver of the Model T car, wrote in an essay about the expedition. The Model T Ford was sturdy, but lightweight and Cap knew replacement parts could be easily found around the world.

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) January 9, 2016

Wanderwell described particularly grueling driving conditions in India and China. She wrote about moments when the team used kerosene in place of gasoline, mixed water and elephant fat for oil, and crushed bananas to collect grease. In 1924, China was also struck by a civil war which made gasoline difficult to come by. She wrote how they had to tow and push the cars through mud and rivers—in Africa, they needed oxen and mules to tow the vehicles.

Grueling, back breaking work to constantly hand pull the Fords out of the river bottoms all the way around the world pic.twitter.com/cFcSV5zSFe

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) May 23, 2016

She was also a fierce feminist, proudly sporting the required breeches and men’s attire. She wrote about one encounter with a particularly snarky clerk in Marseilles:

“That a little thing like a balky clerk in a Marseilles shipping office should stop me on the way to rejoin our expedition was beyond belief. If I had really been a young man instead of being dressed like one in riding breeches, white shirt, leather jerkin and uniform cap, with my leather flying-helmet slung on my blanket rolls and knapsack, the whole story would have been different. As it was, I was a girl who had her own way about most things.”

Aloha & Walter in Japan 1924. Just look at the expressions on their faces. They know they have the World on a String pic.twitter.com/cJU8NP3R9Z

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) February 13, 2016

During the expedition, the Wanderwell’s fell in love and were married in 1925 when they were in the United States leg of their journey. It’s said that the marriage prevented the FBI from arresting Piecynski who was said to possibly be a German spy during the First World War. The couple continued their travels even after having two children, going abroad to Cuba and South Africa. However, Cap’s adventures were cut short in 1932 when he was mysteriously murdered by an unknown assailant aboard the couple’s yacht, The Carma. At first, a previous member of one of the Wanderwell’s trips known to have a grudge against Cap was accused, but his alibi was foolproof and the court found him innocent. Cap’s murder still remains an unsolved crime.

A year after the Captain’s death, Wanderwell married Walter Baker, a former cameraman who helped Wanderwell start his Work Around the World Educational Club. Landecker wrote in her essay that the media had a field day with the murder and Wanderwell’s second marriage, reporting that she was strangely detached from Cap’s death. The couple ignored press, and continued traveling and filming.

Team of oxen towing one of the Model T Fords from the Wanderwell Expedition in Transvaal, South Africa 1927 #Aloha pic.twitter.com/cX0F8rJqq1

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) May 24, 2016

“She kept excellent records, journals, diaries, and scrapbooks during her Around the World trips between 1922 to 1937,” says Diamond. “Unlike Amelia [Earhart], Aloha and Walter filmed every mile for her travel lectures that they would show at each city they stopped in.”

Her descriptions were vivid and captivating. In this excerpt, Wanderwell gives her perspective of the food riots in Germany after World War I:

“There was Germany, with lines of hungry, emaciated persons standing before bakery stores; there were shots fired into crowds, and over everything a terrible, unceasing unrest. It was like traveling along the rim of a spurting volcano.”

Our “Queen of Adventure” Aloha Wanderwell with Chango, her pet monkey, and Walter Wanderwell. Taken in China 1924 pic.twitter.com/ll1cL6I68N

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) February 19, 2016

Many of her photographs and footage are preserved in various museums and educational institutions. Her film of the Bororos people in Brazil, now archived in the Smithsonian, was the first ever captured of the villagers. Wanderwell submitted her documentary Car and Camera Around the World to Henry Ford, but in 1942 he decided that Little Lizzie’s accomplishments on the expedition did not hold enough historical significance to be showcased in the World War II war effort.

“Queen of Adventure” Aloha Wanderwell in a boat with the Bororo Indians of Brazil, she lived with for 6 weeks. 1930 pic.twitter.com/Qaj9eTQidX

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) May 19, 2016

Wanderwell continued to give lectures and presented her experiences throughout the 1970s, and then shifted to curation and collecting footage in the 1980s. She died on June 4, 1996 in Newport beach, California at the age of 89.

While her life is relatively unknown, Landecker describes Wanderwell’s significance in history poignantly, “She presents a quality that we see over and over in this heroine: She never asks permission for anything.”

ALOHA WANDERWEL: SILENT FILM ADVENTURESS

— Aloha Wanderwell (@AlohaWanderwell) March 4, 2016

Presented by Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences®

4:15 San Rafael pic.twitter.com/AA50O51D1o

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook