The Intimacy of Crime Scene Photos in Belle Epoque Paris

Pioneering criminologist Alphonse Bertillon turned everyone into voyeurs.

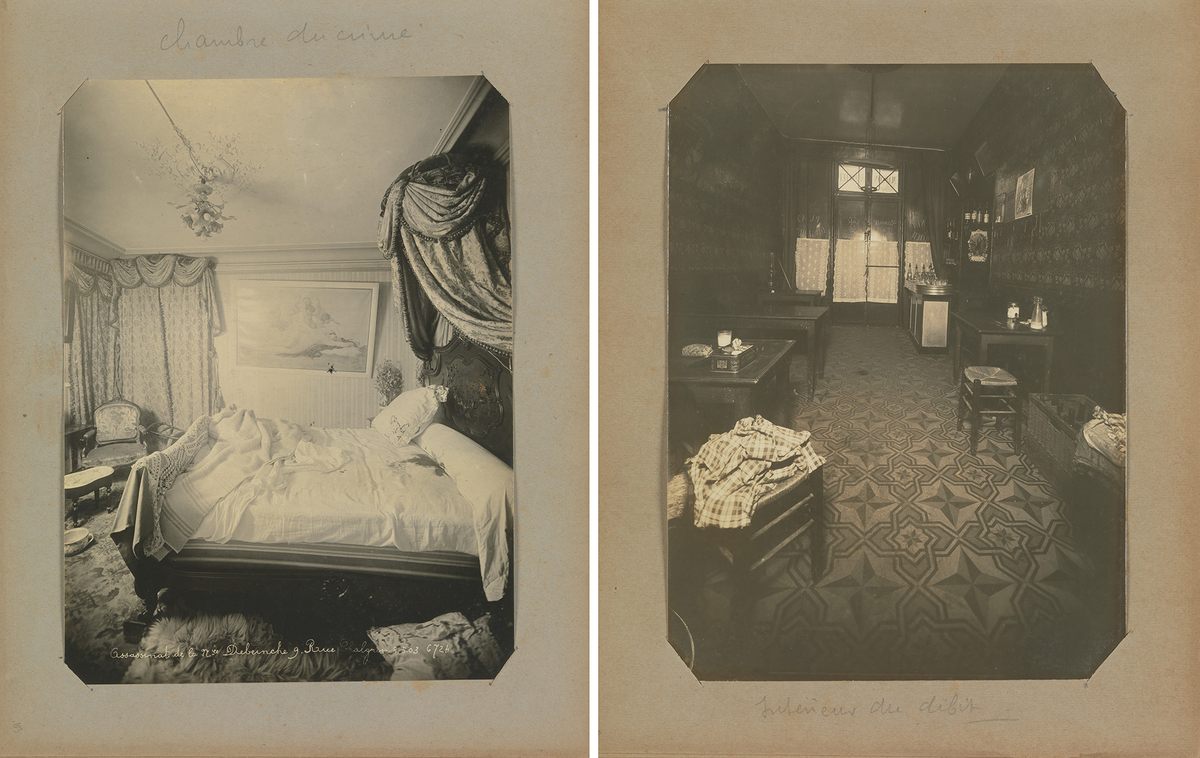

In Belle Epoque Paris, a woman half dangles off a polished wooden bed, as an old-fashioned portrait stares sternly from the wall. Yesterday’s clothes lie heaped on a footstool, never meant for the public’s gaze. Are we looking at a Manet painting of a courtesan? No—there has been violence here. Who invited us to see?

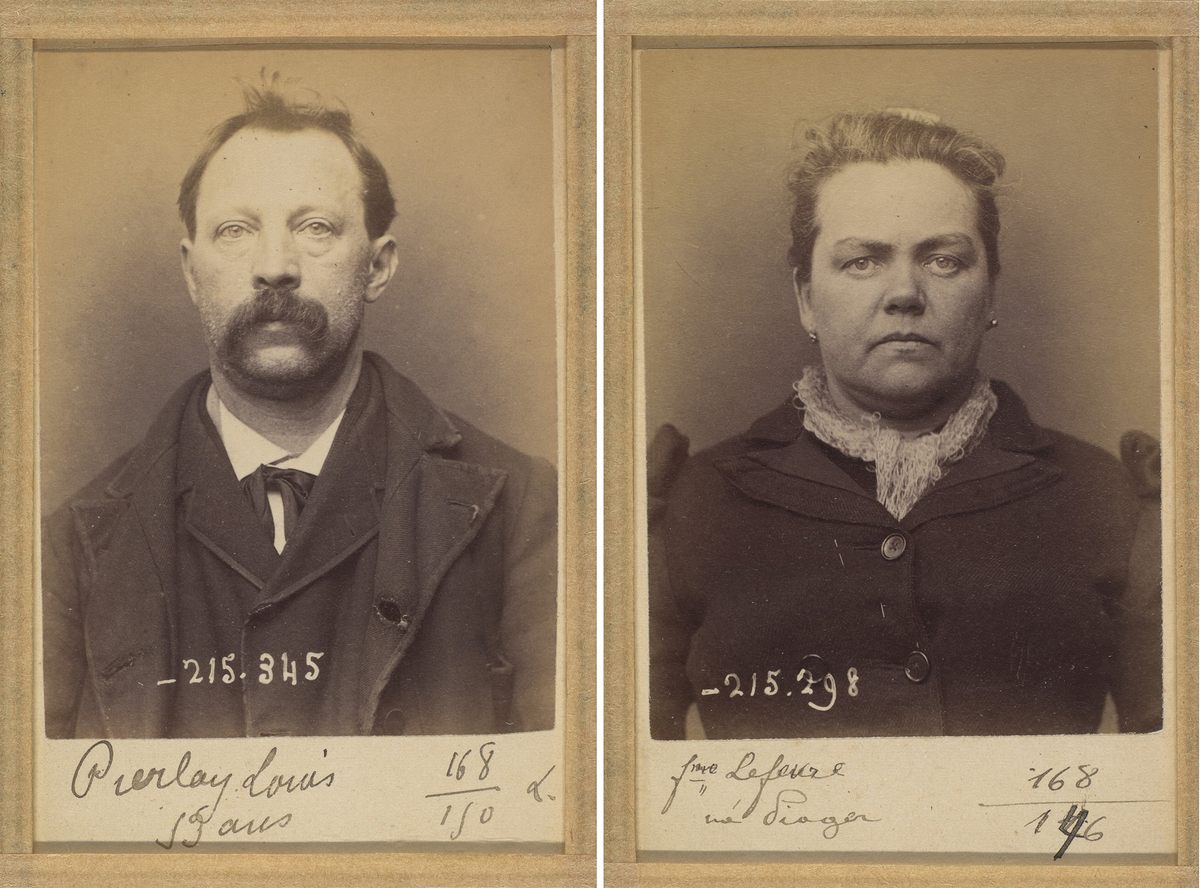

At the end of the 19th century, Parisian police officer Alphonse Bertillon devised a new system of crime scene photography, inviting detectives, jurors, and newspaper readers into scenes of violence and private interiors never so starkly revealed before. Previously, detective work had relied on first-person testimony over circumstantial evidence. Crime scenes were recorded in sketches and notes, in whatever manner the police could manage with the materials they had, free of any standard or system.

The camera, used sporadically since the mid-1800s to take portraits of alleged criminals, was, in Bertillon’s new system, meant to usher in a new era of objectivity in forensics. His approach focused on visual documentation using measurements and uniformity. But what Bertillon’s photographs captured went beyond dry, objective depictions. They featured people whose lives had ended in violence and pain, conjuring a sense of drama that was as much a part of aesthetic and cultural shifts of the time as it was a means toward justice. And these photos weren’t just for investigators. They ended up in newspapers, making private demises shockingly public.

Bertillon insisted on two uniform mugshot poses—full-face and profile—for the accused, and he devised a scientific approach to wielding the camera in the aftermath of a crime. His camera was calibrated so that, given a photograph, detectives could recreate the proportions of a crime scene. It was always placed at a distance of 1.65 meters from the ground, with an average reduction of one-fifteenth, and a focal length of 10 centimeters. Victims were photographed from above, requiring Bertillon to assemble his heavy tripod and camera closely around the body.

Bertillon’s methods resulted in images seemingly taken from bird’s and bug’s eye views. In an image labeled “Assassinat de Monsieur Canon, boulevard de Clichy, 9 Decembre 1914,” a distinguished mustache stands out on a plainly dressed corpse, lying splay-legged on a tiled hallway. Often, a “horizontal plane” shot was added, as in the case of a woman noted in the record as Madame Veuve Bol on the rue de Turenne. The elderly victim looks like she’s fallen asleep on her parquet floor next to her neat, richly made bed. Others look less peaceful: for instance, Mademoiselle Ferrari, whose bed lies surrounded by scuffed walls, a broken mirror, her paltry crockery collection, and last night’s dirty plates. The detective’s caption states that she was killed by her lover, a Monsieur Garnier.

Police departments near and far enthusiastically adopted Bertillon’s system, which helped them sentence serial criminals at a drastically higher rate. Arthur Conan Doyle was an admirer; in The Hound of the Baskervilles, a character calls Sherlock Holmes “the second highest expert in Europe” after Bertillon.

Lela Graybill, art historian at the University of Utah, first saw Bertillon-era crime scene photography in a Paris art gallery. “It was jarring,” she says, to see these carefully calibrated snapshots, taken by police, laid out for spectators. Looking at them, she was reminded of more artistic images from the era, particularly a painting by Edgar Degas, now called Interior (formerly known as The Rape). In the artwork a partially dressed woman poses limply, melancholic, in a cluttered and windowless bedroom, as a man stands blocking the door, looking at her with hands stuffed in pockets. From the ornate wallpaper to the slumped, partly bare body, it’s eerily close to a typical Bertillon composition. The viewer is placed in the position of having interrupted something intimate and sinister. Bertillon and Degas were contemporaries. Although there is no evidence they met, a curator at Paris’s Musee d’Orsay has said Degas’s Interior betrays “the scientific gaze of a Bertillon assistant at a crime scene.”

In a Cultural History article, “The Forensic Eye and the Public Mind: The Bertillon System of Crime Scene Photography,” Graybill says that categorizing crime scene photography “as a form of evidence places it in the realm of empirical science.” But Bertillon saw things differently. “Instead, he suggested that crime scene photography was destined for the courtroom, and for the eyes of the jury,” she writes. “There it would not be a vehicle of objective proof but rather an emotional catalyst for conviction, even vengeance.”

Bertillon himself once wrote that when a jury views grisly images of a murder scene, “there is no man who … does not feel awakened in him the feeling of reprisal that our code calls public vindictiveness.” (Women could not legally serve on French juries until 1944.)

Violence as spectacle, and in the name of law and order, was not new to Parisians in 1904. From March to May 1871, a citizen uprising paved the way for the Commune, a short-lived radical socialist government in Paris. The national government regained control through swift, brutal use of force. “There were mass executions across the city,” says Graybill. “The Paris Commune and its aftermath received extensive photographic coverage.” Though intended more for journalistic purposes than solving specific crimes, this set a precedent for Bertillon’s crime scene photographs. The coverage of the Commune made gruesome images a normalized feature of general-interest papers and magazines.

Police matters were, more and more, repackaged as juicy media stories. Press censorship was abolished in France in 1881, and crime reporting rose steadily. The increasing presence of the camera in police work not only captured murder victims, but exposed the intimate settings of their homes. Generally, in French artistic representations of the time, bedrooms tended to feature courtesans, like Manet’s Olympia, in which a disheveled bed is a pedestal for a defiant-eyed nude woman being presented with flowers. As anyone who’s visited a French household can report, house tours are rarely offered and can feel strikingly discreet: Bedroom doors are usually left firmly closed. As the public suddenly gained access to photographs of crime scenes in the morning papers, they were also put in the position of voyeurs.

Photography was meant to be more exact than a sketch artist, more infallible than a detective’s notes, less vulnerable to sensationalization than a reporter’s impressions.

And yet, despite these efforts at taking subjectivity out of the equation, photography proved itself wide open to it. Bertillon’s own words reveal how crime scenes were seen almost as stage sets or canvasses for the viewer’s imagination of what terrible things might have happened:

The shattered windowpane, the half-open window and the abandoned slippers visible in the left foreground allow the reconstruction in the imagination of the path the assassins took to surreptitiously enter the dark room. You see them lighting the candle that was found on the chair; imagine the fury they experience upon discovering their path blocked by the unfortunate Monsieur R., sleeping like a faithful poodle, though not very vigilant, across the doors of which he defended the access.

In a set of photographs from one murder, known as the Steinheil Affair, Graybill noted that the body had been moved between one photo being taken and the next, as had an alpenstock, a metal-tipped hiking stick, originally lying next to it. By the way it had just been slightly repositioned, she concluded the aim was to help the viewer understand the layout of the apartment. “They’re creating some narrative, not necessarily with malicious intent,” she says. “[T]here was much less of a sense of photographs needing to be completely unaltered or untainted by human intervention.”

The legacy of Bertillon is very much with us. In an everyday sense, Bertillon’s hand is felt every time law enforcement gathers mugshots and scans identity papers. We still rely on photographs to bring to life distant current events and crime scenes. The ideal of photography as a purely objective documentary medium has also stayed with us, though the boundaries of the frame should make it clear that this is a misapprehension. Then and now, photographers decide how their subjects are posed, lit, and cropped, with each decision altering how the image is perceived over the course of its life in the public eye. Even as the camera bears witness to what has happened, it sparks as many imagined reconstructions, interpretations, and emotions as there are individual viewers. In Bertillon’s own words: “One can only see what one observes, and one only observes things which are already in the mind.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook