America’s Oldest Boat Shop Has Been Making Hunky Dories for 226 Years

Lowell’s preserves tradition—and maintains relevance—by adapting to the times.

As a gentle breeze blows through the open windows and Lyle Lovett croons on an old Sony boombox, workers and volunteers at Lowell’s Boat Shop do what they’ve always done. Saws buzz, sandpaper scrapes, and lumber bangs on floorboards coated with decades of sawdust and paint. Outside, on the Merrimack River, a line of wooden dories are moored near the shop. Cormorants sun themselves, wings outstretched, atop the gunwales.

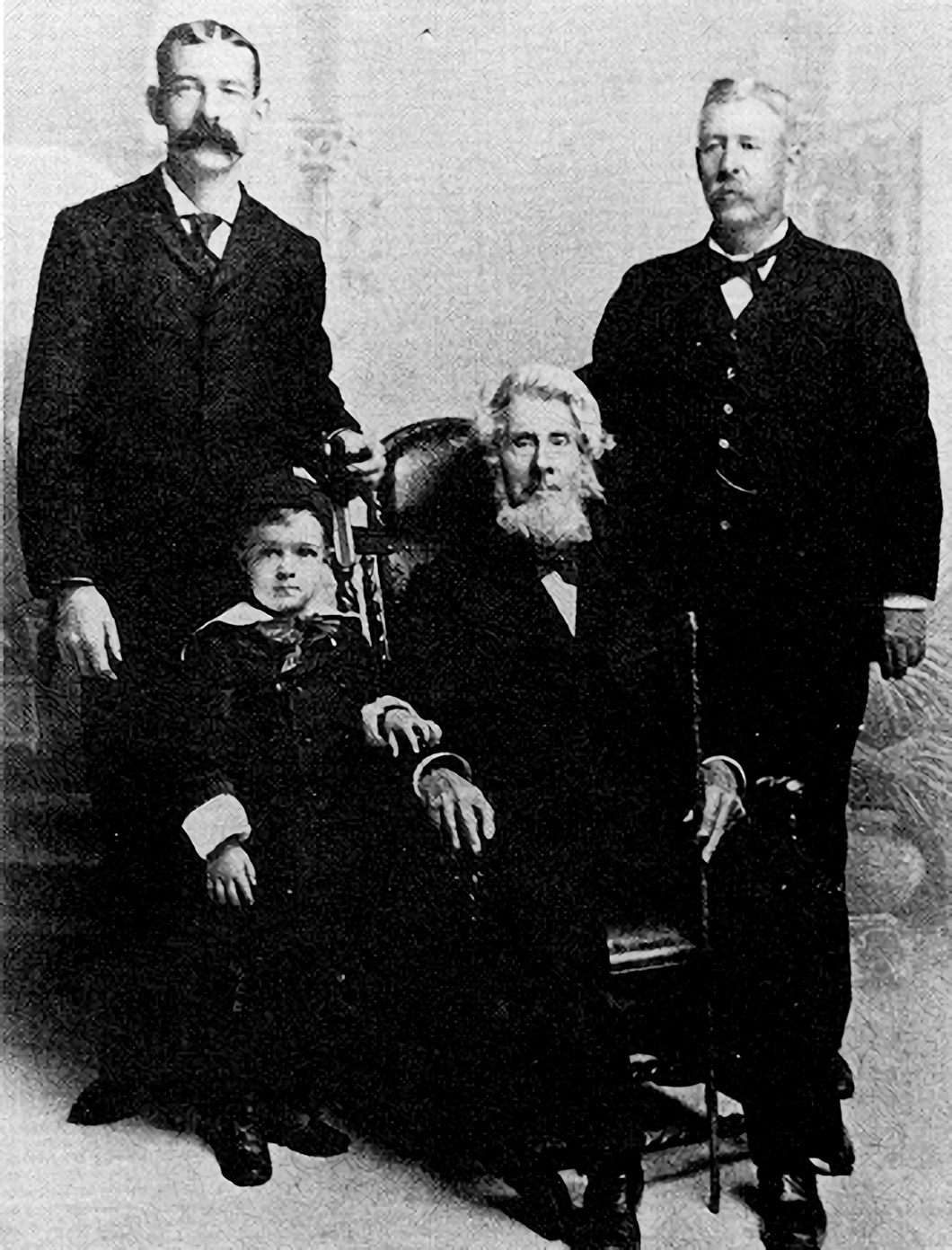

Lowell’s is the oldest continuously operating boat shop in America. Located in Amesbury, Massachusetts, it’s both a national landmark and a working museum—emphasis on working. Founded by Simeon Lowell in 1793, it was passed on to Benjamin Lowell, then to Hiram Lowell, and kept in the Lowell family for seven generations, until 1976. (After that it was bought by the Odell family, then the Newburyport Maritime Society, and finally, in 2006, Lowell’s Maritime Foundation, an independent nonprofit.)

The shop is famed for its dories—boats with wide flat bottoms and a simple construction that once abounded in these waters. Over the course of two centuries, more than a quarter of a million dories were produced in the U.S.

At Lowell’s, annual production was tracked on a beam inside the shop, where the years and numbers of boats produced were engraved—the way a parent might chronicle a child’s growth, ticking marks onto a door frame. In 1911, at the peak of its production, Lowell’s built an astonishing 2,029 boats—the prime engine of a then-mighty fishing fleet based in nearby Gloucester.

That vast output was possible thanks to the shop’s design and manufacturing innovations. Simeon Lowell made radical changes to traditional dory design, creating boats that were more durable and efficient than those that had come before. Thanks to their design, Lowell’s dories could be stacked neatly on larger ships—a key step when Gloucester fishermen, eager to boost production, began deploying fleets of dories from the decks of their schooners, rather than fishing from the schooners themselves using hand-lines.

The business was also one of the first in the nation to employ a sort of factory-type manufacturing. “Historically, the way it was done, these boats were mass produced,” says Graham McKay, the shop’s master boat-builder and current executive director. Each worker, he says, was responsible for a step in the building process, and the shop became like an assembly line. To improve efficiency, pieces of the boats were prefabricated. (During Lowell’s heyday, from the late 19th century into the early 20th, they could all be purchased from factories in downtown Amesbury.)

As the shop teems with workers on a sunny Monday, McKay explains the process. He points to a trap door in the attic through which stored prefab pieces were dropped to the main floor of the shop. There, the frames, stem, and transom were nailed to what would become the boat’s bottom—“literally bang[ed] … together,” says McKay. The design was so streamlined, “you could almost have every piece made ahead of time.”

Once the base of the boat was built, the next step was to create the sides, through a process called planking. The lowermost plank of the boat’s hull, called the garboard, was fitted against the bottom of the boat. One by one, the next planks were added up from the garboard, against the frame of the boat, until the complete hull was formed—creating the boat’s shape from the ground up.

Lowell’s dories were planked using what’s called a lapstrake method, where the planks of the boat’s hull overlap one another; the bottom of each new plank was laid over the top of the plank below, up to the top. The increased thickness from these overlaps made the boats strong.

Once all the planks, from the garboard to the top, were overlaid and nailed to the frame, rails were fitted at the top. These fully assembled boats were carried to a door in the side of the building. Shop workers lowered them there, first to a deck by the river, then into a paint room in the lower level of the shop.

Workers there mixed the paint’s ingredients—white lead, turpentine, pine tar—together in a barrel. At one point in the early years, brick dust would be mixed in as well. “It made for a [distinctive] salmon-colored paint,” McKay says. “But it also made it kind of chalky. So it would rub off, versus flake off.”

At its peak, Lowell’s made an average of seven boats per day using this technique. Today, the shop builds about that many boats in a year. McKay and the shop’s three other boat-building employees—along with dozens of volunteers—also do repairs and restorations.

But it’s only partly a commercial shop. These days Lowell’s has multiple revenue streams, including grant money, visitor donations, and the funds it generates from the boat-building classes McKay offers for kids and adults. The shop also hosts events, like rowing races; has an active presence on Instagram; and offers a membership program. It’s become less about building boats, and more about building a community around them.

“Most people preserve things by putting them behind glass,” says McKay. “We preserve … things by continuing to do them and use them.”

Some of the tools still in use at Lowell’s attest to this fact. A band saw, for instance, dates back to the late 1800s. A thickness planer, which takes a piece of wood and makes it thinner and thinner as it’s fed through and cut down to size, is from World War II. “They’ve always worked,” says McKay, “and they still work for what we’re doing.”

McKay grew up down the street and once took a boat-building class at Lowell’s himself, during high school. That’s where he first learned how to build dories the traditional way. After leaving home to work on tall ships and in boatyards, he came back about 10 years ago, when Lowell’s needed someone to run the shop.

“I didn’t realize that I was one of the few people around that knew how to do it—to use those notes and go through the process,” he says.

Now, he’s passing that tradition along, not just teaching students how to build boats but also cataloguing the slew of archival dory plans in the shop’s attic. He does his best to ensure that the plans he and the students use to build their boats are as close to the originals as possible. At Lowell’s Boat Shop, it seems, what’s old is new again.

As they’ve repaired and restored old vessels over the years, the boat-builders at Lowell’s have used a few modern technologies to identify—and prevent—recurring issues. In the 1970s and ’80s, for instance, the shop would slather the insides of its dories with epoxy, which creates a waterproof seal that prevents leaks. Now, the shop incorporates fiberglass into its boats, which makes them more durable.

Jeff Lane, a boat-builder and instructor at Lowell’s, is experimenting with a foam bottom for a 20-foot-long surf dory—a tack some boat-builders take to add stiffness and buoyancy. It’s something Lowell’s has never tried before—“it’s crazy by the standards around here,” Lane says—though it’s not exactly a novel technology.

It’s all a balancing act, says McKay—figuring out how to introduce modern innovations to a time-honored tradition, without changing what worked so well in the first place. That includes the materials. Most of the wood Lowell’s uses is still pine (from a mill just over the New Hampshire border) and locust (which is milled in the shop), just as it’s always been. “We use those because they’re local, they’re historically what was used, and they still work totally fine,” says McKay.

Today the museum drives a large part of Lowell’s traffic, and helps keep the shop afloat. A small exhibit space occupies what was once the paint room, where thousands upon thousands of dories were painted over the years. The remnants still cake the floors here, at some points thicker than the floorboards themselves, forming what McKay calls a “paint glacier.” There are also a few placards in this room, along with display cases and a television, mounted on the wall, that plays a video about the founding and progression of Lowell’s and its dories.

The goal of the museum space, which opened in 1994, is to give thousands of visitors each year—in 2017 there were 4,680—a sense of Lowell’s enduring place in the maritime industry over two centuries. But while they may appreciate the historical context, says McKay, “their primary interest is in what we’re doing now.”

That includes one of the shop’s current projects: restoring a replica of a light sailboat from the 1620s. Called a shallop, it’s a vessel that the Mayflower would’ve brought with it to America. Lowell’s is rebuilding this one to mark the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival in the New World. (Visitors will have to see it while they can, before it’s returned to Plymouth next April.)

When McKay first started at Lowell’s, he says, the place was pretty dead. “I was basically here by myself all day long, working on boats.” Now, he says—with the shop’s high-school apprentice program, a bustling events calendar, class offerings, and a healthy supply of volunteers—“you can’t get a day to yourself here unless it’s snowing out.”

Lowell’s is located on Main Street in Amesbury, which runs alongside the river. People drive by all the time, says McKay. He hopes that the shop’s maritime timelessness will continue to be a draw for curious visitors, and their donations.

“We exist now to host people who are interested in this kind of thing, and we just want them to come,” he says. It’s the educational aspect, the human interest, that keeps Lowell’s alive. It relies on people these days, not boats. If they cease to visit, Lowell’s will cease to exist.

But the best reason for visiting Lowell’s ultimately comes back to quality. “Your reputation relies upon making good boats that last,” McKay says. “And if you don’t adapt with the times, then you’ll go out of business. This place has always adapted with the times, which has kept it in business.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook