Why an 1875 Map Imagined the U.S as a Giant Hog

New York is the nose, Alaska the tail, and Cuba is a giant sausage.

This story ends with an eccentric entrepreneur distributing 2,500 maps of the United States in the shape of a pig to a gala of Civil War veterans. It begins with sewing machines. Grover and Baker sewing machines, to be precise.

In 1849, William Baker, a Boston tailor with little formal education, had a problem. The newly invented sewing machine didn’t work as well as he needed. So in 1851, alongside fellow tailor William Grover, Baker obtained the patent for an innovation that changed the industry forever: machines with a pair of needles that could create chains of interlocking stitches. Their invention took off, and Baker and Grover teamed up with other sewing machine manufacturers to form a trust. They made a killing.

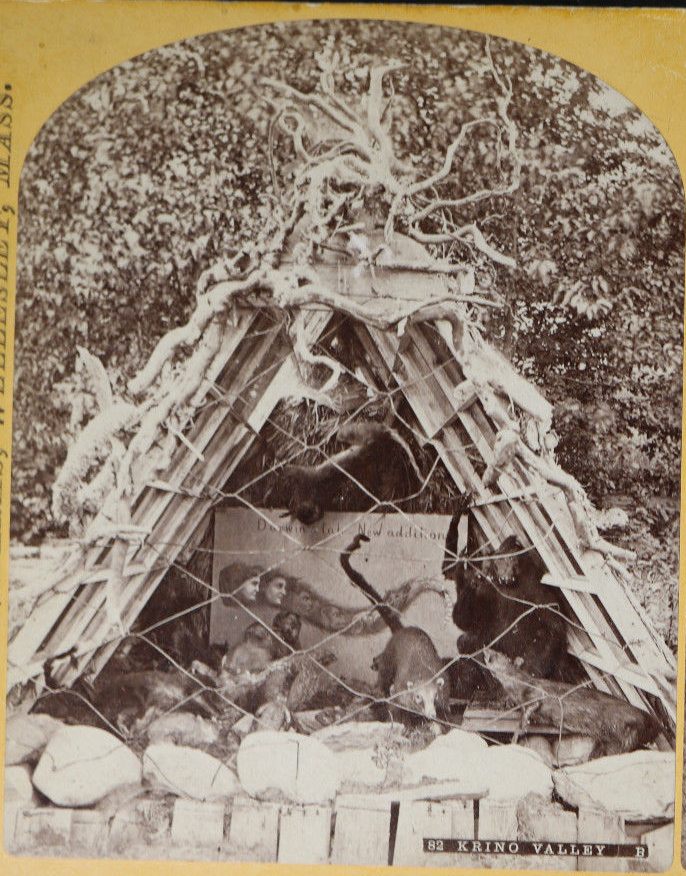

“At the age of 40, the trust was about to run out, so he decides to sell out and retire,” says Gloria Polizzotti Greis, Executive Director of the Needham History Center and Museum. It was 1868, and Baker, astronomically wealthy and barely middle-aged, moved to an 800-acre summer estate in Needham, Massachusetts. There, he built an amusement park that included a 225-room luxury hotel, a pleasure lake, saloons, restaurants, two bear pits, an underground crystal grotto, and a diorama of Darwin’s theory of evolution that contrasted stuffed monkeys with an artfully placed mirror revealing the human onlooker’s own face. Most prized of Baker’s many attractions, however, was a state-of-the-art hog butchery facility he dubbed “the sanitary piggery.”

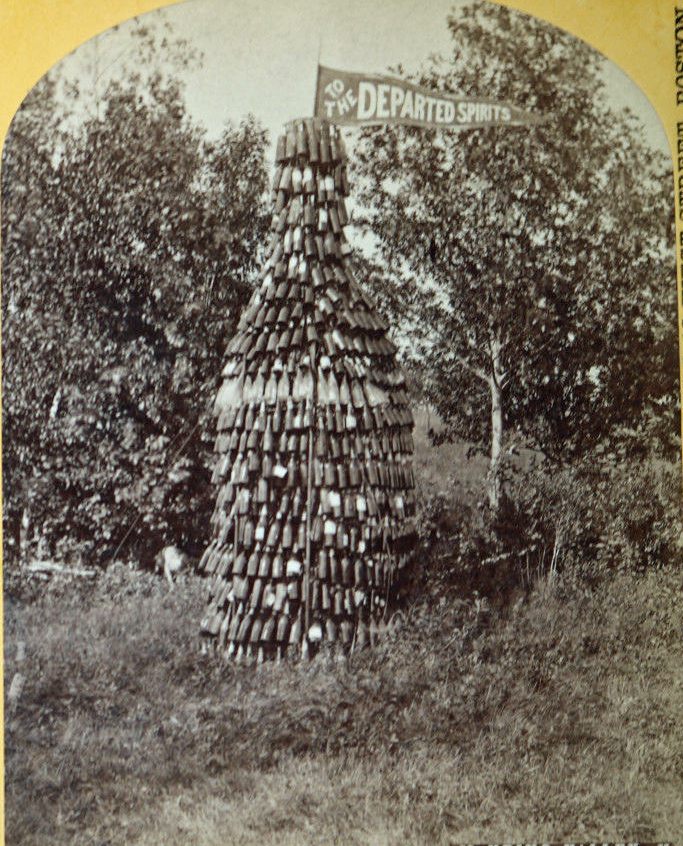

Baker’s interest in social causes was as sprawling as his acreage. He invested in the post-Civil War reconciliation of the North and South, women’s education, and a collection of elaborate statues of groan-worthy puns (he called one sculpture of a giant bottle, made of empty liquor containers, “A Monument to The Departed Spirits”).

But first among Baker’s interests was public health. Specifically, the burgeoning field of food science. That, combined with his love of pork, gave rise to a bold hypothesis: If farmers raised pigs in hygienic conditions, they could eliminate food-borne disease.

Today, says Greis, that idea may sound like a no-brainer. But in 1875, the germ theory of disease was hardly common knowledge. While Americans relied on pork as a staple meat, pigs were city animals, raised on scraps from urban kitchens and street refuse. “If you think about what pigs are likely to find in a city street, in a day when horses still pull the carts, it was pretty horrific,” says Greis.

Baker’s ideas reflected an age of feverish cultural change. The Civil War and its deprivations were over, and rapid industrialization led to growing cities that were laden with opportunities for the exchange of goods, ideas, and pathogens. According to Benjamin R. Cohen, a professor of engineering studies at Lafayette College who has written a history of the pure food movement, food production after the Civil War rapidly shifted from local cottage industries to industrial conglomerates. Tainted products were common.

In response to this trust deficit, a coalition of scientists, religious reformers, and progressive female activists founded the pure food movement. They approached their work with evangelical zeal. “It was a crusade,” says Cohen. “Between 1877 and 1906, they proposed 190 separate pure food bills in Congress.”

But when Baker unveiled his sanitary piggery in 1875, the pure food movement was just beginning. “He was ahead of his time,” says Susan Schulten, chair of the Department of History at the University of Denver and a historian of American cartography. Baker hatched a plan to secede his estate from the town of Needham and create his own independent “hygienic village,” “Hygeria,” a scheme that the Massachusetts state legislature shot down.

His porcine endeavors, meant to model sanitary livestock practices and accompanied by a hygienic cooking school, were more successful. “The sanitary piggery was going to revolutionize how people made pork,” Schulten says. Baker’s hogs were kept in such pristine conditions, he liked to joke, they slept in their own miniature beds with blankets and pillows.

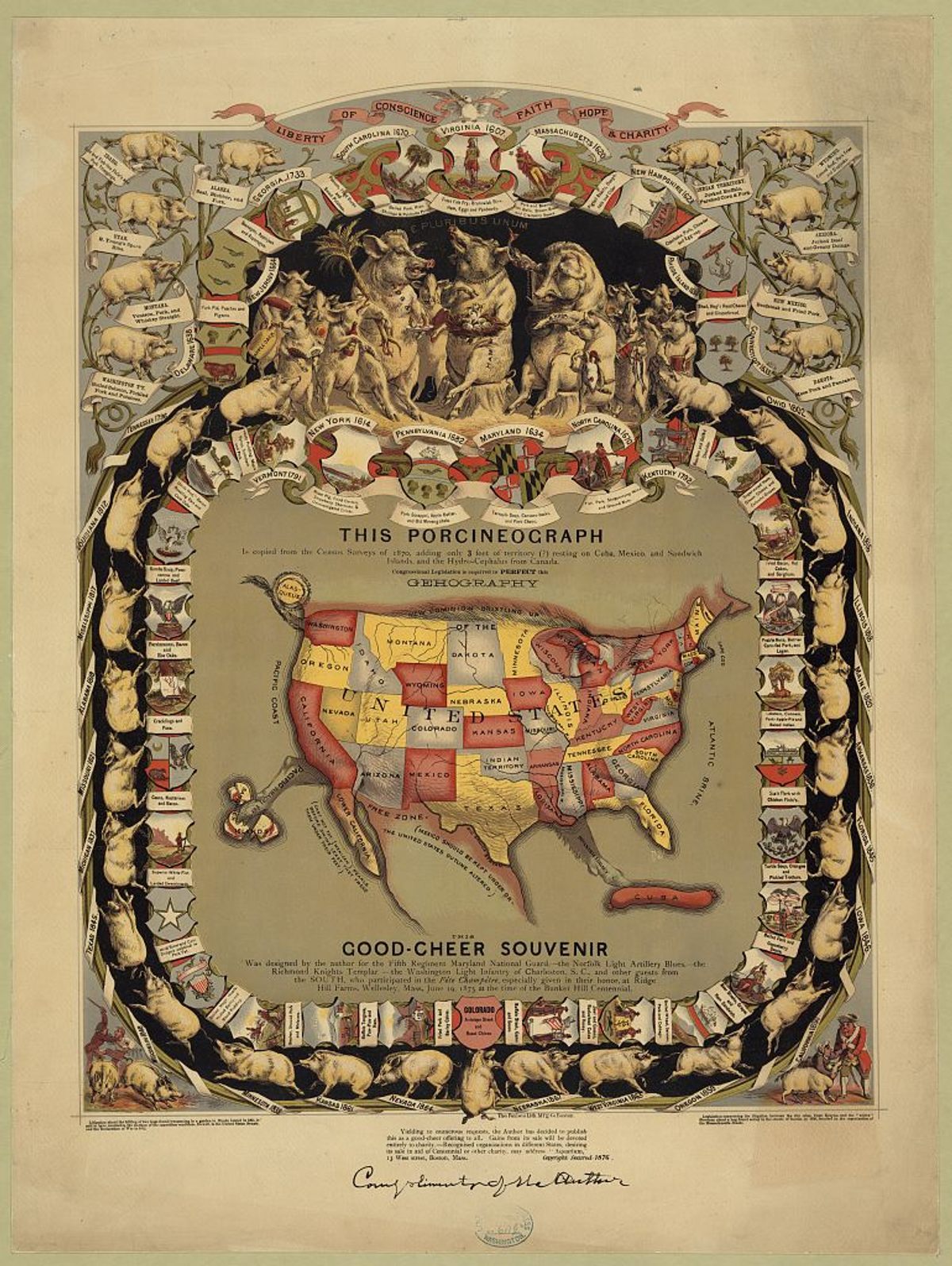

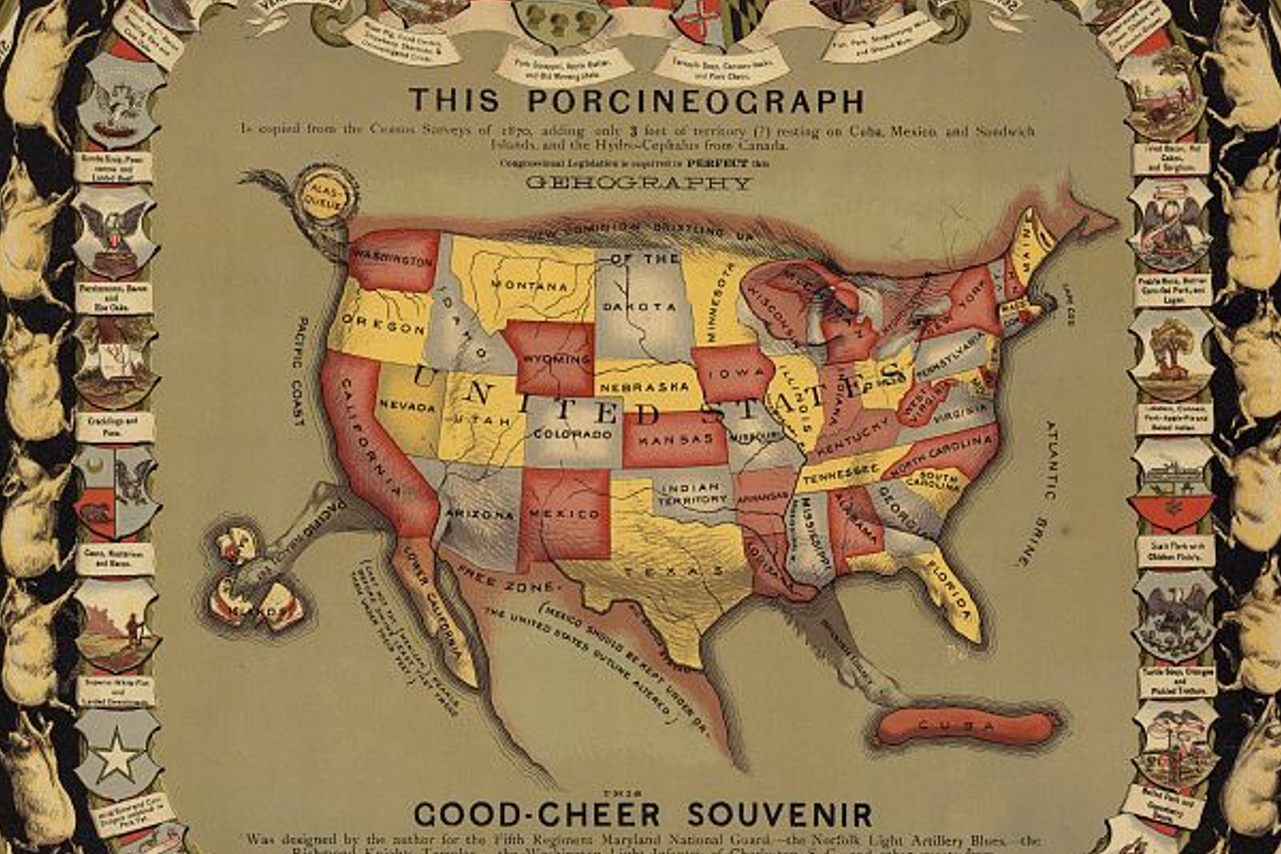

One starry night in 1875, Baker threw an opulent gala. The fête, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, had two aims: to bring former Union and Confederate soldiers together for a night of good-natured excess, and to celebrate the sanitary piggery. At the end of the evening, each of Baker’s guests left with a “good cheer souvenir,” a map of the United States in the shape of a pig. The country’s snout was Maine, its bum California, the tip of its tail touched Alaska, and its Florida-shaped hoof stomped on the plump sausage of Cuba. Baker called it the “Porcineograph.”

Around the edges of this fanciful chart, bright with the new technology of color lithography printing, was a symbol of each state, complemented by a signature pork dish. The dishes are equal parts familiar (gumbo for Louisiana and pork and beans for Massachusetts) and fanciful (antelope and roast pork for Colorado, and bear steak, grapes, and ham sandwiches for California). The map also included notes on famous legal cases involving pigs in U.S. history, meant to convey, says Greis, that “pigs are responsible for the foundation of American democracy.”

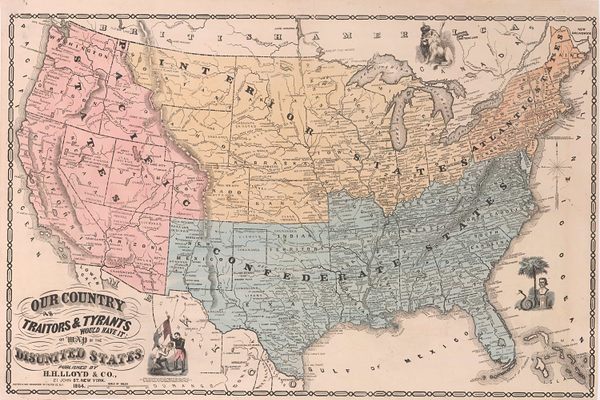

Even these imaginative leaps reveal the aspirational zeal of Baker’s vision for the United States. At a time when the Union had barely been saved, when the purchase of Alaska was widely regarded as a waste of money, and the West consisted of an assemblage of territories and newly incorporated states, Baker’s map depicted one country from coast to coast. “It has everything to do with a desire to bring the country back together,” says Schulten. Pork was the glue.

Baker’s Porcineograph also bears hints of the more sinister side of both American expansionism and industrialization. Many Western territories were still contested, with white settlers violently seizing land from indigenous Americans. At the same time, the United States was beginning to turn its attention to empire beyond its shores, a trend perhaps unintentionally evoked by the image of the U.S.’s pig feet stepping on Hawai’i and Cuba. Indeed, the very notion of “pure food” was, like much science of the time, mired in racist ideas of ethnic purity, which frequently spiraled into xenophobia. For some food activists of the time, says Cohen, “what’s right and proper is that which is more white and more pure, which is a racist perception.”

Still, says Greis, Baker’s innovations contributed to a movement toward food safety that benefitted immigrants and poor city dwellers. Baker himself died in 1888 of a heart attack, perhaps spurred by the heartbreak of learning that the Massachusetts government had denied him permission to build his sanitary village. Baker’s wife, who had never been a fan of her husband’s hobbies, sold off the estate soon after his death, and the piggery was disbanded.

Yet Baker’s legacy lived on, in the training of those who had attended his sanitary cooking school and in the plentiful donations he had given to educational institutions. A century and a half later, the map depicting American “Gehography” is a reminder of a cultural moment where Americans such as Baker dreamed of a reunited country powered by industrialization and replete with clean pork for all.

“It’s a little bit of his moral outlook, a little bit of his political outlook, a little bit of his belief in the way to improve public health,” says Greis of what Baker meant to convey with the Porcineograph. “And a little bit his belief in the overwhelming superiority of pigs.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook