We’ve Been Debating Foie Gras Since Ancient Times

Early Egyptians and Greeks force-fed geese, ducks, and hyenas.

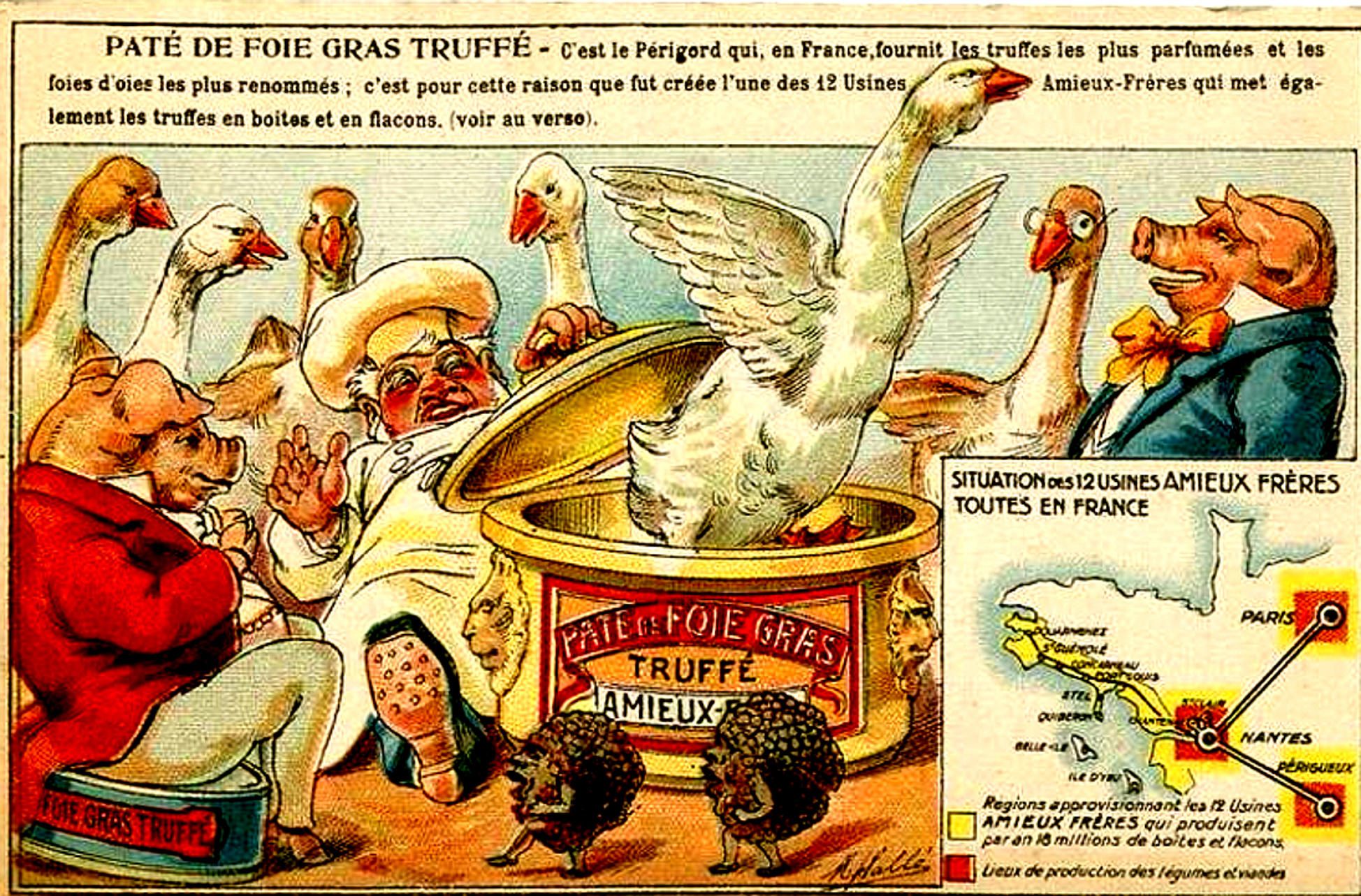

The force-feeding of geese to produce foie gras is one of the most controversial practices in food today. The process is known as gavage and is most associated with France, where the parliament recently declared it a part of the country’s cultural heritage—in defiance of bans in other areas. But humans all over the world have been force-feeding animals to fatten their livers (and debating whether or not to do so) for millennia.

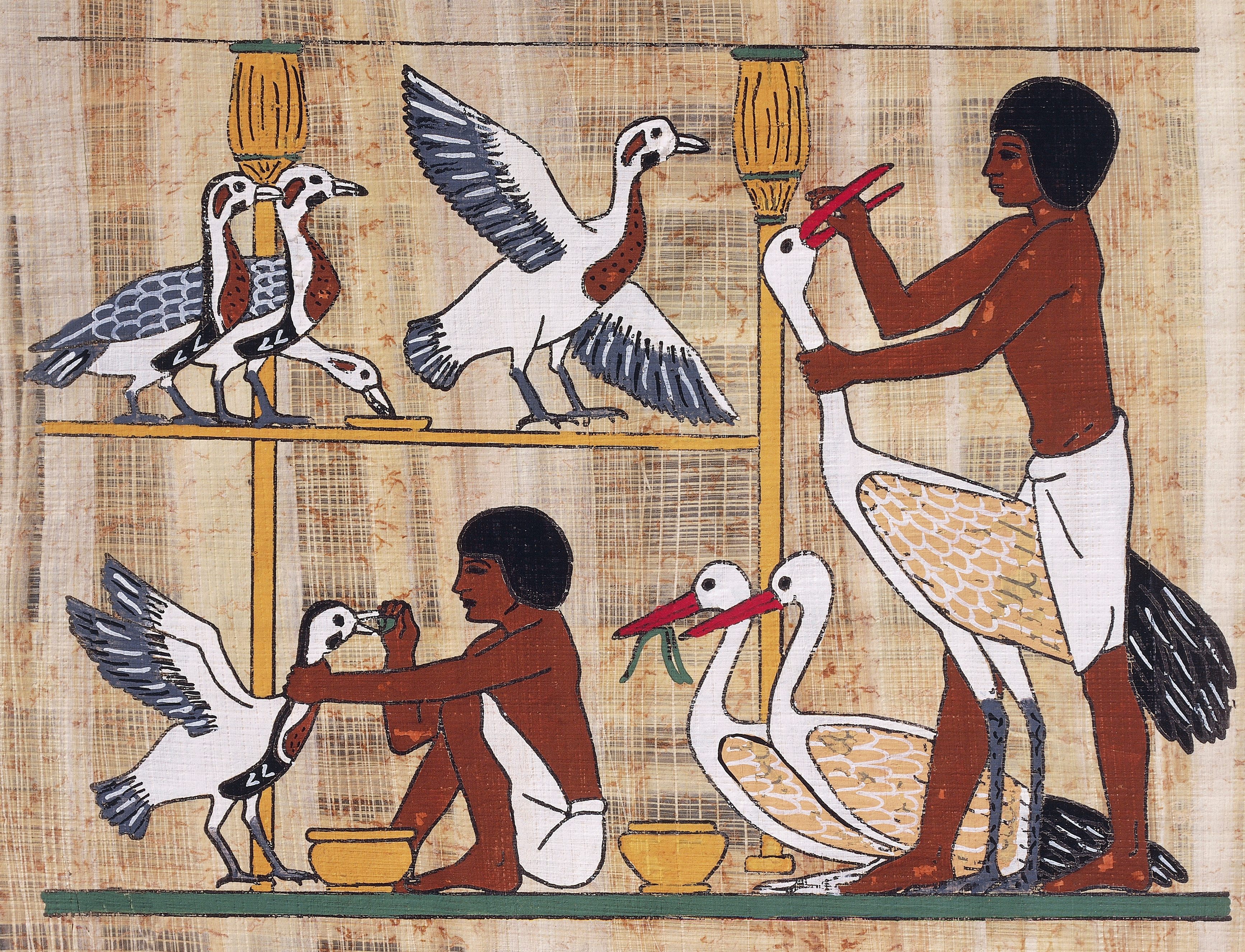

Foie gras production takes advantage of how waterfowl prepare for long migrations by eating extra calories, which they store as fat deposits in their livers and under their skin. The Egyptians were the first to replicate this natural process by shoving food down the throats of geese, ducks, and cranes, depicted in Egyptian wall-reliefs as far back as 2500 BC. Birds were not the only victims; other Egyptian artwork depicts cows too fat to walk being transported by cart, and even the force-feeding of hyenas. It’s unclear whether Egyptians specifically prized the livers of these animals. The primary motivation for gavage in Egypt was the production of animal fat, which they used in everything from hair-loss remedies to the famous Egyptian eyeliner.

Gavage appears to have spread from Egypt to Greece at an unknown date—Homer’s Odyssey (written around the 8th century BC) contains the earliest written reference to fattened geese. In the 4th century BC, we find the first mention of their livers as a delicacy.

Force-feeding later spread from Greece to Rome, where it was expanded into a sinister art form. Roman pigs had food crammed down their throats in the same manner as geese, while tiny dormice were tricked into pre-hibernation binges by being kept in total darkness and surrounded by nuts. Not even snails were safe; the Roman cookbook Apicius instructs chefs to remove the operculum (the little door that snails use to seal their shells) from live snails before feeding, so the animals will be unable to return to their shells and will swell to unnatural size.

Ancient people force-fed their birds with grain or moistened flour pellets (much like modern producers of foie gras), but at some point, the Greeks began to use dried figs. The Romans added a grisly innovation by giving a drink of honeyed wine to their fig-stuffed geese and pigs. The resultant moisture and gases expanded the dried fruit in the animals’ stomachs, causing a fatal case of indigestion. Liver thus harvested was called iecur ficatum in Latin, iecur meaning “liver” and ficatum meaning “figgy.” Over time, the original word for liver was dropped, and the dish enjoyed as ficatum. This gave rise to the word for liver in the modern Romance languages: Italian fegato, Spanish hígado, and French foie. So whenever people discuss foie gras, they unknowingly reference figs.

We shouldn’t assume from the popularity of gavage in the ancient world that there were no objections to animal cruelty. The first-century writer Plutarch makes his position clear in a diatribe called On the Eating of Meat. “For the sake of a little flesh,” he laments, “we deprive [animals] of sun, of light, of the duration of life to which they are entitled by birth and being … Begging for mercy, entreating, seeking justice, each one of them say[s], ‘I do not ask to be spared in case of necessity; only spare me your arrogance! Kill me to eat, but not to please your palate!’” It’s worth noting that, though a Roman citizen, Plutarch was Greek, and his position on animals has more precedence among the Greeks than the Romans. In the same text, Plutarch supports his argument with the example of early Greek philosophers who encouraged vegetarianism on moral grounds.

While no author in antiquity specifically opposes the practice of gavage, several display disapproving sentiments towards eaters of foie gras. For the Greeks and Romans alike, diet was seen as a reflection of character. Rich, expensive food became a symbol of decadence and corruption, and those who ate it invited criticism. In a satire by the Roman poet Horace, guests at a banquet refuse to try “a white goose liver fattened with succulent figs” because the pompous host won’t shut up about his elaborate menu: “In revenge, we took off, leaving him there, without tasting a thing.” The Emperor Elagabalus, who was vilified as extravagant, was said to feed his dogs nothing but foie gras.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, foie gras and gavage all but disappeared from European tables under the influence of Medieval Christianity, which ranked gluttony among the deadly sins. Meanwhile, European Jews, restricted by religious law from cooking with butter or lard, turned to force-feeding poultry as a source of fat, just as the Egyptians had done thousands of years before. Foie gras did not see mainstream popularity again until the 16th century, when Renaissance chefs started buying goose liver from local Jewish communities.

With increased concern about the welfare of the geese themselves, some modern farmers have developed ethical foie gras, produced from birds that gorge of their own volition. Many others continue the practice of gavage, producing a divisive delicacy so ancient that its name refers to its own long history. The debate over foie gras and force-feeding continues, except now we leave the hyenas out of it.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook