The Wit and Wisdom of Ancient Jewish Graffiti

Researchers in the field have uncovered related messages ranging from “Lasius is a pervert” to “Good luck in your resurrection.”

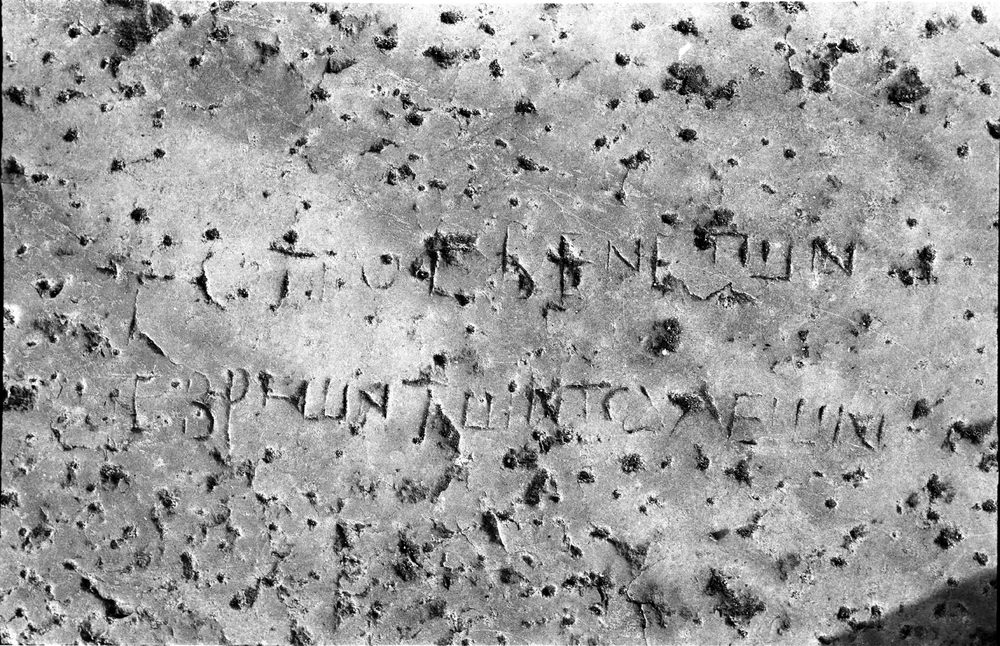

![Greek dedicatory inscription of Samuel, son of Saphara. Painted onto ceiling tile from the Dura‐Europos synagogue, which requests “may he be remembered [who] founded these things thus.”](https://img.atlasobscura.com/bRQnOESmi-7aQA44sHAj8T0S6NuhQRt54OgpBHFyBFo/rs:fill:12000:12000/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9jMWJjMzg5NjJj/MWM3M2EwMTNfYWct/b2JqLTU3MDktMDAx/LXB1Yi1wcmludC1s/Zy5qcGc.jpg)

“You will come to an evil end if you rob this grave” and “My beloved was here” ranked among the most popular messages for graffiti writers in ancient Jewish communities.

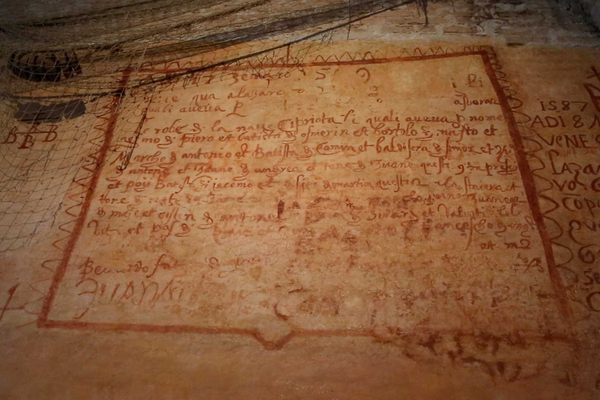

Starting some 3,000 years ago, Jews scratched walls at homes and public spaces with prayers, warnings, blessings on deceased relatives, and store advertisements. They even used graffiti to mark rows of theater seats that were reserved for Jewish groups. In the margins of the texts, they sketched outlines of ships, people, menorahs, and synagogue columns.

Carving the letters and images “required time, diligence, steadfastness, and a degree of pain tolerance,” Karen B. Stern, an assistant professor at Brooklyn College, observes in her new book, Writing on the Wall: Graffiti and the Forgotten Jews of Antiquity. As the graffiti artists hammered away at doorways, pillars or cliffs, she writes, “powders and fragments would cover one’s face and fill one’s lungs with dust; hardened dirt, rock, and plaster could push back and split fingernails; and carving implements, including metal nails, blades, and stones, surely drew blood when the lighting faded or surfaces grew unwieldy.”

She has documented graffiti written by Jews, dating back as early as the 8th century B.C., at archaeological sites from modern-day Croatia to the Persian Gulf. Clusters survive at the Dura-Europos synagogue in eastern Syria, El‐Kanaïs in Egypt along the Nile near Aswan, the Beit Shearim necropolis in northern Israel and the Aphrodisias ruins in western Turkey. They come in a babel of languages, including Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic, Lihyanite, and Nabataean. Some people who carved the walls were clearly uneducated, while others used neat handwriting that indicates elite upbringings. Interspersed are markings from non-Jewish neighbors: pagan sayings, Byzantine crosses, and praise for Allah.

Dr. Stern notes that for countries that have been torn apart by religious strife, and places where hardly any Jews live anymore, the graffiti now serves as evidence of past centuries of peaceable coexistence. Privileged and ordinary people of many faiths all had the same habit of emblazoning their names, interests and accomplishments on the walls. Decoding the inscriptions, Dr. Stern says, sheds light on those who left few other traces on the sands of time: “It’s about paying attention to voices that have otherwise been drowned out.”

Travelers with Jewish names wrote on El‐Kanaïs’s cliffs, to record how many times they passed through the area. At Aphrodisias’s theater, Jews used graffiti to label and reserve some rows of seats close to the stage. At the hippodrome complex in Tyre, in southern Lebanon, a female merchant named Matrona painted a wall with a menorah outline plus her name, as well as references to her market stall’s inventory of purple cloth. Dr. Stern explains that Matrona’s signage reveals the relatively tolerant atmosphere of ancient Tyre. Although it was dominated by Christians and Samaritans, Jewish business owners there including women felt comfortable advertising in front of thousands of hippodrome ticketholders.

Relatives of Jews buried in Beit Shearim’s tombs etched its passageways with crude pictures of ships, tear-stained mourners and armed gladiators, to transport, comfort and protect the dead. In one catacomb, an inscription in Greek wishes visitors “Good luck in your resurrection.” Dr. Stern says she does not know if the graffiti author was sincerely hoping to impart good fortune, or instead showing signs of a “morbid sense of humor.”

Scholars have long dismissed archaeological graffiti as “random and incidental,” Dr. Stern says, and there have been few attempts at systematic documentation. (Major studies so far have focused on Pompeii and Herculaneum, where the Latin and Greek scribbles range from cryptic mentions of cheese to insults like “Lasius is a pervert.”)

The last century of global warfare has erased untold wisps of ancient graffiti in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. More destruction occurs constantly in regions engulfed in unrest, where insurgents target archaeological sites. Carvings have also vanished due to looting, neglect, and vandalism. Well-intentioned restorers have done damage, too, by smoothing out surfaces without realizing which scratches on the walls represented important words from the past.

Dr. Stern plans to create an online database of Jewish graffiti, which can be updated as more examples surface. “Sometimes it’s accidents that produce exciting finds,” she says. People plowing fields or excavating basements still uncover ruins sometimes, where someone Jewish once engraved messages to grieve, scare away thieves, market local products or save seats for some cousins.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook