How a Newspaper Article Saved Thousands of Black Gospel Records From Obscurity

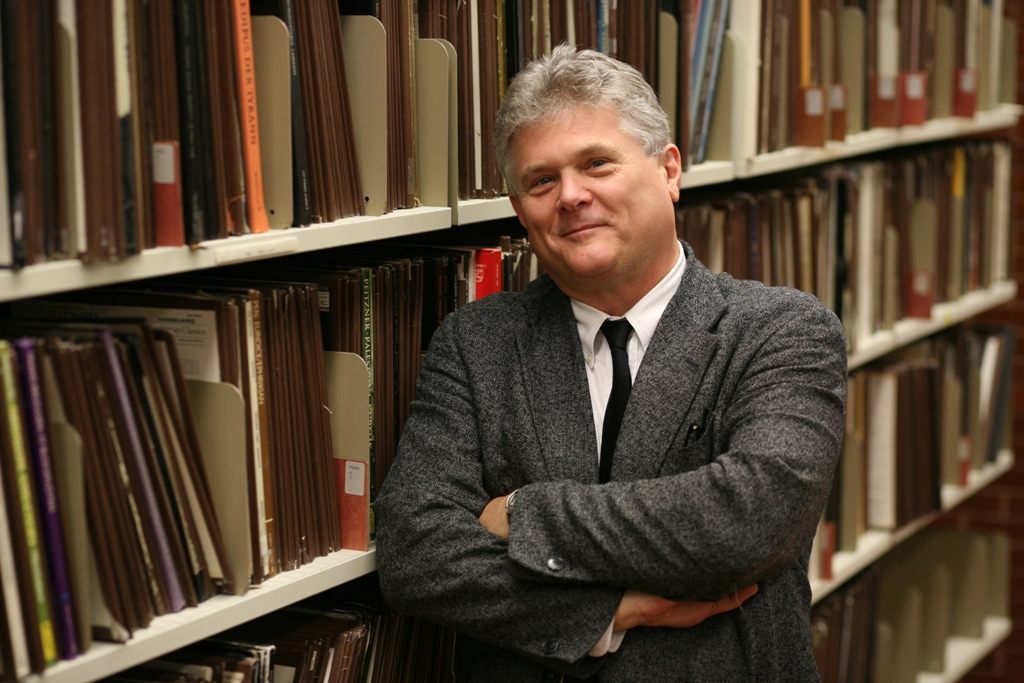

A professor in Texas collects and digitizes rare recordings from across the country.

For the last dozen years, in the basement of a university library in Waco, Texas, a small team of audio engineers has been busy trying to save black gospel music. On a typical day, after delicately removing a scuffed vinyl record from its tattered sleeve, an engineer cleans the disc, places it onto a specialized turntable, and drops the needle. A moment later, an exhilarating music rises from the speakers, filling the small room with voices not heard in half a century. Once the song has come to an end, the audio file is loaded into a digital archive, and the record joins thousands of LPs and 45s that are stacked wall-to-wall in a climate-controlled room at Baylor University.

The current effort to preserve gospel recordings began in 2005, when Robert Darden, a journalism professor at Baylor, published an op-ed in The New York Times. He wrote that innumerable black gospel records, particularly from the “Golden Age” of the mid-1940s to the mid-70s, were at risk of being lost, whether because of damage or neglect. It was getting harder and harder to track down LPs of popular artists like the Soul Stirrers (who at one time featured a young Sam Cooke), to say nothing of 45s from largely obscure groups like the Gospel Kings of Portsmouth, Virginia. “It would be more than a cultural disaster to forever lose this music,” Darden wrote. “It would be a sin.”

Soon after publishing the op-ed, Darden was contacted by an investment banker named Charles Royce. Royce confessed he didn’t know much about gospel music, but the opinion piece had convinced him that preserving it was a worthwhile endeavor. “You figure out how to save it,” he said, according to Darden. “Send me a plan, and I’ll pay for it.”

Darden first began to recognize the crisis facing classic gospel music while working on his book, People Get Ready!: A New History of Black Gospel Music. He had previously worked as the gospel music editor for Billboard, and had written extensively on the genre, yet he often struggled to find the music he covered. “I’d been frustrated time and time again throughout the writing of the book, when I would write about a very important gospel song that had been influential in the history of gospel music, in some cases in popular music, and I couldn’t listen to it,” Darden says. “I’d go to the used record stores, and online, and everywhere I knew, and there just simply would not be a copy available.”

Darden and other record collectors estimated that around 75 percent of all gospel vinyl released during the Golden Age was no longer available. The records had been completely lost, or only a few remaining copies were known to be in circulation. Darden was determined to know how many of these records could be found, and how many were lost for good.

After Darden came up with a plan to find and preserve these records, Royce provided a grant of $350,000. Darden got right to work, establishing the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project, or BGMRP, in 2007. Inside a sound-isolated room in the basement of Baylor’s Moody Library, gospel LPs, 45s, and 78s are cleaned, archived, and digitized by audio engineers, using state-of-the-art equipment. After each disc is processed, it becomes available to stream for free online, alongside any available original artwork and recording details.

One of the rare songs that Darden helped recover was “Old Ship of Zion,” recorded on a self-pressed 45 in the early 1970s by the Mighty Wonders, a group from Aquasco, Maryland. Darden recalls the first time he heard it: “Our engineer played it for me in the studio, and we both broke into tears.” Found in a box of miscellaneous 45s purchased on the East Coast, Darden spent the next five years trying to track down any information about it. During a public radio interview in Baltimore, a child of one of the original members of the group called in and introduced himself. Darden learned that the group itself didn’t even own a copy. Now one of the BGMRP’s most cherished finds, “Old Ship of Zion” is featured in the gospel section of the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

Most of the music in the archive was loaned by collectors across the country or purchased at record stores by Darden and his team, but some have come from individual donations. Anyone is welcome to send music, either as a permanent donation or a loan. Darden says that opening a new box of records is “like Christmas.” Many of the records now in Baylor’s library, like the “Old Ship of Zion” 45, are among the only known copies in existence, Darden says. He estimates that he and his team have digitized around 14,000 items, including songs, LP jackets, and photos.

In a 2007 interview, shortly after launching the project, Darden told the public radio host Terry Gross, “We see it as kind of like those seed banks up around the Arctic Circle that keep one copy of every kind of seed there is in case there’s another Dutch elm disease. I just want to make sure that every gospel song, the music that all American music comes from, is saved.”

Darden, who is white, doesn’t come from a traditional church background. With a father in the Air Force, he grew up moving with his family from base to base. His parents owned a record of Mahalia Jackson singing Christmas songs, but Darden remembers first hearing gospel music in the homes of his black friends, whose parents were also in the Air Force. “That was the music that their parents were playing and singing,” he says. “I loved it from day one.”

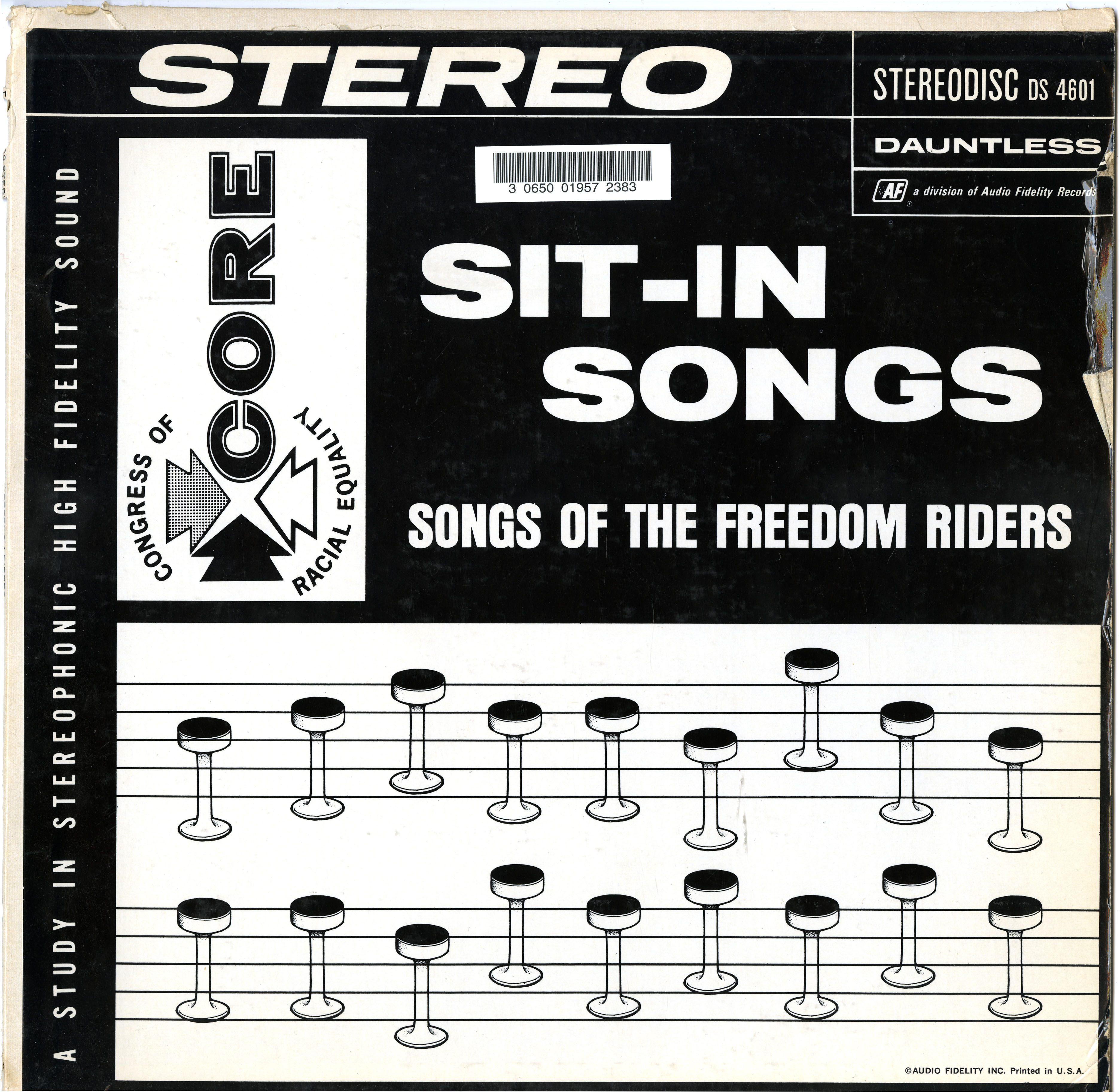

The BGMRP focuses exclusively on music from gospel’s Golden Age, the roughly 30-year period that saw gospel music surge in popularity, owing to the musical innovations of artists such as Clara Ward, Mahalia Jackson, the Swan Silvertones, and the Dixie Hummingbirds. Darden points out that gospel’s Golden Age is also significant because it “corresponds with the era of the Civil Rights movement exactly, and it corresponds with the era of the greatest impact of the African-American church on the African-American community.” He adds, “They’re all intertwined. That’s why gospel matters. This was the music of the revolution.”

Reverend Clay Evans, a Baptist pastor in Chicago who has worked as a civil rights leader and gospel recording artist, has powerful memories of the Golden Age. He was born in 1925 and recorded numerous albums in the 1970s and 80s*, mostly with the record labels Jewel and Savoy. “Gospel music motivated us,” Evans says. “Music gave us hope. Hope that we needed to continue to overcome. Hope that we were on the right trail to overcome the racism that existed. Hope that God was with us in the struggle.”

These days, selections from Baylor’s collection can be found in the National Museum of African American History & Culture, in Washington, D.C., as part of the museum’s permanent collection. But to access the entire collection in-person, visitors to Waco can drop by Lev’s Gathering Place, at Baylor University’s Crouch Fine Arts Library. Sitting on a reclaimed church pew and stained-glass windows, visitors can view photos and listen to thousands of songs on iPad kiosks.

In recent years, Darden and the BGMRP have begun another undertaking: archiving audio recordings of African-American preachers. Recorded sermons were once popular and profitable, especially leading up to and during the Civil Rights movement, but they too face the threat of being permanently lost. “Even less of that has been preserved,” Darden says. “From the Civil Rights movement, for instance, with the exception of Dr. King, virtually none of the sermons that changed America are preserved. Or, when they are preserved, they’re on somebody’s cassette in somebody’s warehouse in the South Side of Chicago.”

Upon learning of this project, Reverend Evans dug out several boxes of his broadcast sermons, some decades old and long-neglected, from a derelict storage space near his church in Chicago. Now 94 years old, Evans has contributed over 900 tapes of his broadcast sermons to the archive. For him, digitizing and archiving these records is about not only preserving a fundamental part of American history, but also providing inspiration to present and future generations.

“We face the same issues today, and we still need encouragement,” Evans says. He sees parallels between today’s struggles for social justice and the civil rights struggles of the past. “It’s good for children to know what we’ve been through. Then they can be encouraged to make it through, too.”

*Correction: This article originally stated that Reverend Clay Evans released his first musical project with Savoy Records in 1985. Evans released albums with Jewel Records in the 1970s.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook