The Delicious Universe of Asian Culinary Comics

These food cartoons fight stereotypes, share memories, and tell forgotten histories.

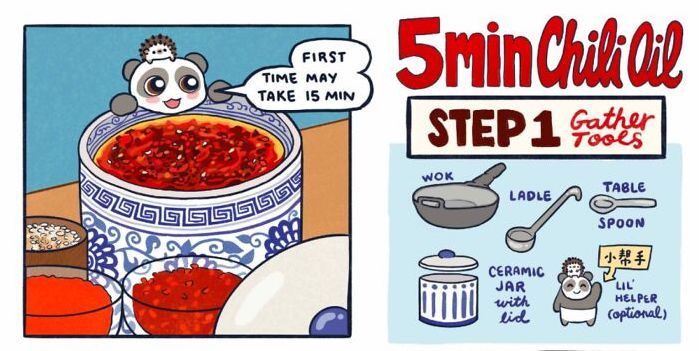

Illustrator Linda Yi’s recipe for “smacked cucumber,” a classic summertime Chinese snack, is more than a list of ingredients and instructions. It’s a full-color comic strip, complete with speech bubbles offering supportive cooking advice, sound effects (“SMACK!”) and a cat and panda beating up a cucumber.

When it comes to telling stories about food, “there’s so much that you can do with both words and pictures,” Yi says. Across North America, a generation of Asian cartoonists have come to the same conclusion. The last decade has seen a flurry of illustrated Korean cookbooks, one-panel satirical comics about South Asian chai, and graphic novels about Japanese-American culinary history. No matter the focus, each cartoon offers vivid depictions of the artists’ beloved foods.

Asian culinary comics in North America go back at least to the late 1970s, when Vietnamese-Canadian artist Thach Bui and chef Bill Lombardo created the nationally syndicated, decades-long comic strip Cheap Thrills Cuisine, in which a character named Chef Peppi walked readers through recipes inspired by Toronto’s Asian and other immigrant communities.

Culinary comics are a natural result of the Asian diaspora’s devotion to both food and visual storytelling, says Taiwanese-American writer Jeff Yang, the editor of multiple anthologies of Asian-American comics. In the United States, Asians-Americans are better represented in the world of comics and graphic novels than they are in almost any other major storytelling industry. “A part of our cultural heritage may make us more inclined to see words and pictures as being a little bit more blurred together,” Yang says, citing pictorial Chinese characters, South Asian calligraphy, and Japanese manga comics. And when it comes to visual storytelling, images of food are inevitable, he says. “Food as a way of showing love or respect or caring is so deeply embedded in every one of our Asian ethnic cultures that if we want to tell a story, especially a personal story…food becomes a critical lens.”

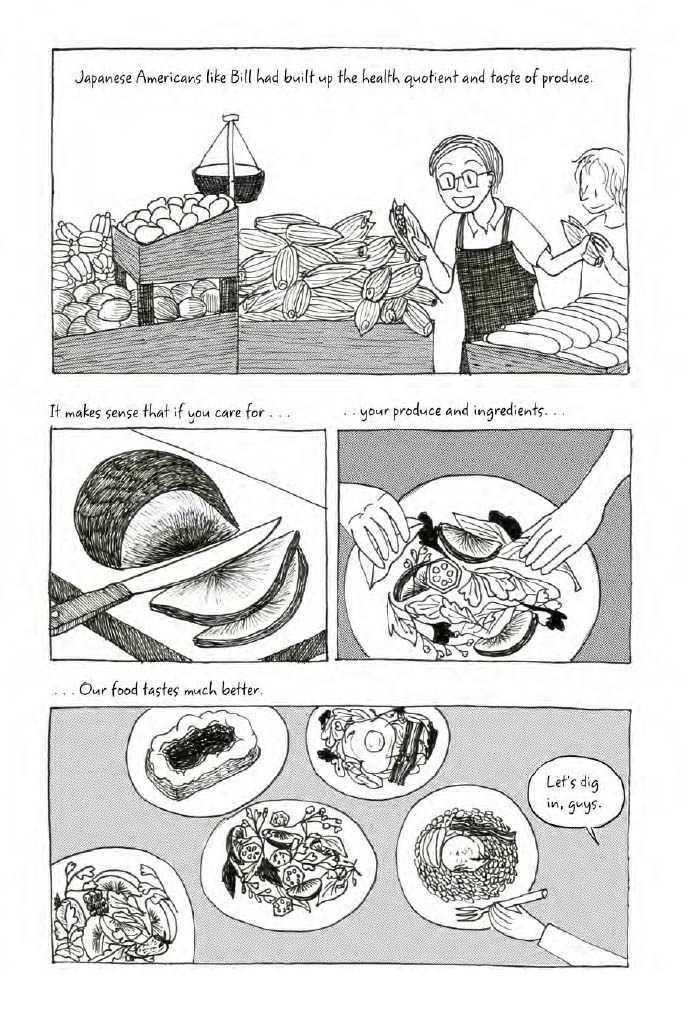

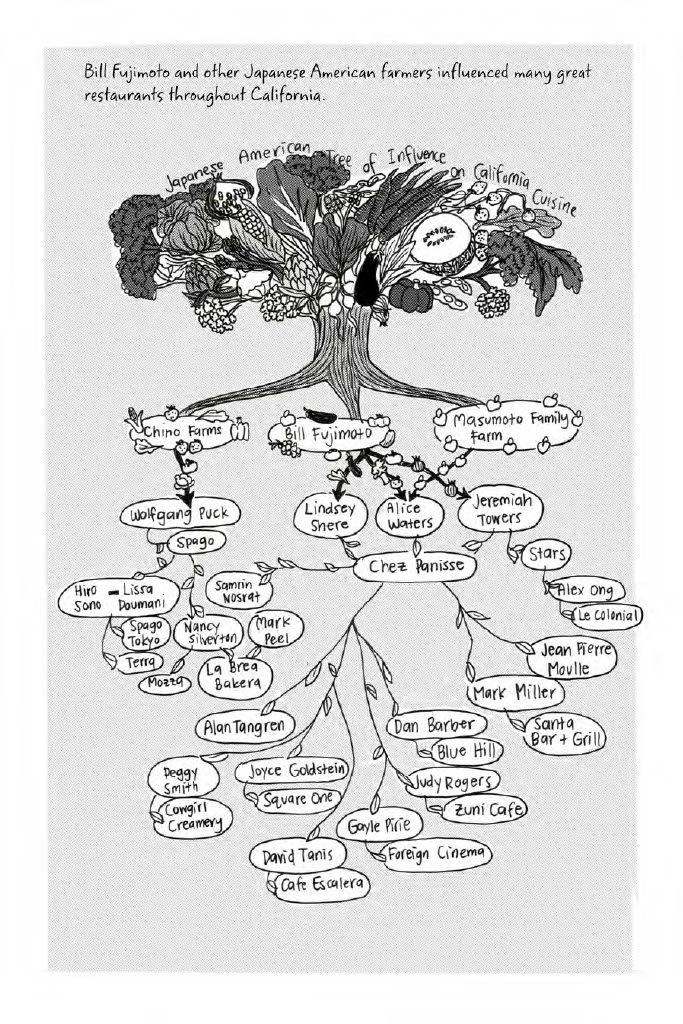

Asians’ embrace of comics also comes out of necessity. “We were locked out of so many other storytelling platforms,” says Yang, but comics could be published in a do-it-yourself fashion with a pen and a Xerox machine—or, in the internet era, a blog and a laptop. Japanese-American illustrator Sam Nakahira self-published their graphic novel Bill’s Quiet Revolution: A Japanese American Artisan of California Cuisine in 2019 while attending Grinnell University. A California native, they were captivated by the story of Bill Fujimoto, a Bay Area grocer whose devotion to quality, local produce inspired the likes of Alice Waters during the 1970s. Their book, a journalistic narrative that depicts Bill’s work in Monterey Market surrounded by lemongrass and heirloom gourds, helps set the record straight about the Japanese-American role in California cuisine. Nakahira has received messages of appreciation from Japanese-American farmers throughout the state for her comic.

The art of Yi and Nakahira is a sharp departure from the negative stereotypes of Asian food that have long circulated in American and Canadian culture. “Food slurs are so common as frames for us. [They call us] dog eaters, right?” Yang says. Cartoonists reframe the food of Asian immigrants in a familiar, positive light, he says. “We have yet to be in the world of scratch-and-sniff storytelling,” but with visuals, he says “we can show people what [our food] looks like.”

A slate of Asian food comics tackle culinary racism head-on. Filipino-American illustrator Joshua Luna’s Sus-Mayo-Osep! depicts two white children turning their noses up at a Filipino classmate’s food in a school cafeteria in one frame, and those same children as adults praising a White chef’s Filipino cooking in the next frame. In Just Eat It, Malaysian-American artist Shing Yin Khor illustrates a letter to a White friend, criticizing the way he eats Malaysian food for cultural caché while ignoring the humanity of the people behind it. The comic also upends romantic stereotypes about beloved Malaysian foods, with drawings of Mcdonald’s Happy Meals and Maggi seasoning rendered just as affectionately as those of bak kut teh, a pork rib stew.

Perhaps the most radical thing about these culinary comics is that they provide a space for Asian artists and readers to be themselves. Many offer glimpses into artists’ personal lives: the warmth of cooking with a parent; or the joy of eating with a partner. In Korean American Cooking Comics, illustrators and partners Sung Yoon Choi and Eric Watkins pair recipes with humorous panels depicting their domestic life, such as a recipe for a Pepsi float alongside a cartoon of Choi and Watkins binging on potato chips, or a recipe for o jing u cho mu chim, tangy spicy squid, alongside the two of them fishing in a boat, waiting for a bite.

In portraying the human stories behind dishes, these cartoons often convey cultural context in ways that would be difficult with writing alone. In Robin Ha’s comic-cookbook hybrid Cook Korean!, she pairs anecdotes about the history and culture of Korean dishes with visual recipes. “You can say kimchi is a fermented cabbage, but kimchi means so much more to Koreans than just a pickled vegetable,” she writes over email. Accordingly, her book’s “Kimchi and Pickle” chapter opens with a group of women in Korea making huge batches of kimchi amidst fall leaves in preparation for winter. “I’ve gotten many messages from the readers telling me that they are Korean adoptees or Koreans who were born in America, and my book was their introduction to the culture around the food that they’ve grown up eating,” she writes.

Yi, who began drawing her Panda Cub Stories comics during the COVID-19 pandemic to satisfy a longing for her family’s Sichuanese cooking, says that drawing allows her to vividly express the feeling of a tingling tastebud or the image of a sizzling clove of garlic. With text alone, she might struggle to portray Sichuan’s famous mouth-numbing ma flavor, but she can get the point across by drawing a mouth with “little stars, tap dancing across your lips and tongue,” she says. Plus, she noted that drawing out her parent’s recipes has helped her master difficult recipes, which her ADHD used to prevent her from doing. Illustrated ingredients, dramatized cooking steps, and cute animal narrators have helped her and many others learn to cook complicated dishes such as mapo tofu.

Most of all, Yi says, her comics are an accessible, fun way to share her love of Sichuanese culture with her readers.Many of her fellow creators are similarly motivated, she believes. “Part of it,” she says, “is our generation returning to the foods that we grew up with—and, sometimes we’re ashamed of—and then being like, no, these are beautiful.” Her art, a delicious collage of drawings and words, speaks for itself.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook