At Harvard Forest, Cameras Track Your Every Move

(Photo: Courtesy of PhenoCam)

On the surface, there is nothing unusual about the Harvard Forest. It’s a typical New England woodland littered with golden maple leaves in fall, new black cherry buds in spring, and covered in layers of snow by the winter. Sometimes, you can hear porcupines and bobcats crunching along its understory, and then you can go dip your fingers in its burbling streams.

But the Harvard Forest is more than just a pretty wood—it’s busy at work decoding a complex carbon story. This forest has sensors that every hour, measure the breath between trees and the atmosphere. Devices tap flow rates in the streams, PVC pipes peek up from the soil, scientists glean data up in the trees, and an 85-acre “sea of yellow-lined trees” is used to quantify the forest’s growth, says Clarisse Hart, Harvard Forest’s Outreach and Development Manager—a nice measure for how much carbon goes into each tree.

A sequence of early morning images from May 15, 2014, in the Harvard Forest (Photo: Courtesy of PhenoCam)

Since 1988, the plot of oak, maple, and pine has been a Long Term Ecological Research site. This is a prestigious title granted by the National Science Foundation to areas that can help us understand how climate change influences the way carbon moves through an ecosystem, “which ends up driving everything else,” says Hart, who also directs the Fisher Museum at the Harvard Forest.

By faithfully surveilling this single plot, Harvard researchers believe some of their findings may reflect how forests worldwide are responding to global climate change. So far, the forest foresees a carbon-filled future with lots of bugs, more sneezes and itchy eyes and a newly defined season (think winter, only shorter).

Of all its scientific bells and whistles, the forest’s most standout contraption is a nearly 100-foot tower topped with a phenoCam, named after the study of phenology: how life cycles relate to season. Towering over four different wooded plots, the color-sensing cams let the forest snap a canopy overhead shot for each thirty minutes of its life. These images upload through an invisible network of wireless internet swarming through the forest, then up into the cloud—the same cloud to which your private iPhotos are presently synced.

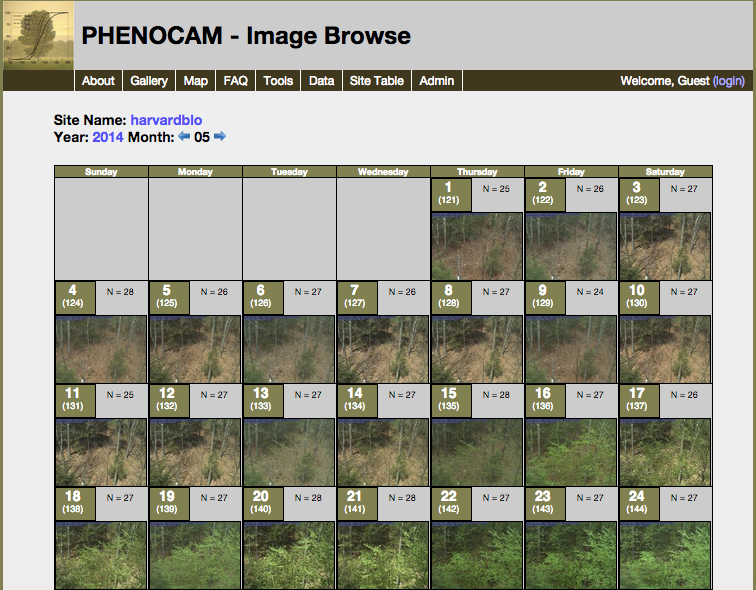

A calendar of images showing changes to the Harvard Forest in May, 2014 (Photo: Courtesy of PhenoCam)

The result of these woodland selfies is a lovely digital gallery documenting the transformation from golden brown to new green each year. Paired with on-the-ground leaf observation and satellite photos, phenocams have exposed remarkable findings. As carbon levels swell in our atmosphere, we see that spring is arriving much sooner in the forest.

In the Harvard Forest, everything is connected. So with spring coming so early, and the growing season lasting longer, the Harvard Forest seems to be holding onto more carbon than it once did, says the Forest’s site and research manager Audrey Barker-Plotkin. “Conventional wisdom says that as forests age, they should be slowing down their carbon sequestration,” she says. “They can’t hold as much.” With the Forest now over 100-years-old, it’s fascinating to see sequestered carbon “just keep going up, up, up,” Barker-Plotkin says. She adds that the forest scientists can’t be sure if this means that the trees are reacting to the extra carbon in the atmosphere.

(Photo: Courtesy of PhenoCam)

Deeper into the plot, a hemlock woods is withering under the influence of a climate-driven beetle invasion. “Years ago you would have seen this thick green canopy and now what you see is thinning and gray,” says Barker-Plotkin. These invasive insects have been feeding on and killing hemlock trees across the East Coast since the 1950s. What once kept the bugs in check was cold weather, says Barker-Plotkin, but as winters are turning warmer, the beetle can spread deeper through the hemlock’s range. In the past decade, the beetle’s range spread some 20 miles a year across the Eastern seaboard. In parts of the Great Smokey Mountains in Tennessee, beetles have demolished as many as 80 percent of the region’s hemlocks.

These examples all reveal how extra carbon is already swaying a forest ecosystem. But the Harvard Forest can also predict. To find out what a carbon-laden future may feel like, forest scientists are meddling with carbon levels. With a little more of the gas strewn in the atmosphere—or in this case, greenhouse—the common allergen plant Ragweed switches the type of pollen that it produces. The released pollen is more plentiful and more allergenic, says Hart—a nasty sneak peek for the allergy sensitive or to those with respiratory problems. Quite a few other studies foresee a similar future.

It’s powerful to see such lucid results as these: Leaves greening a week strangely too soon and the presence of a bug in regions just recently too chilly for it. For a phenomenon so obscure as the wiles of carbon, these visual testimonies seem to be the best teachers. It’s remarkable, says Hart; we get to witness “evidence of global change just on a walk through the woods.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook