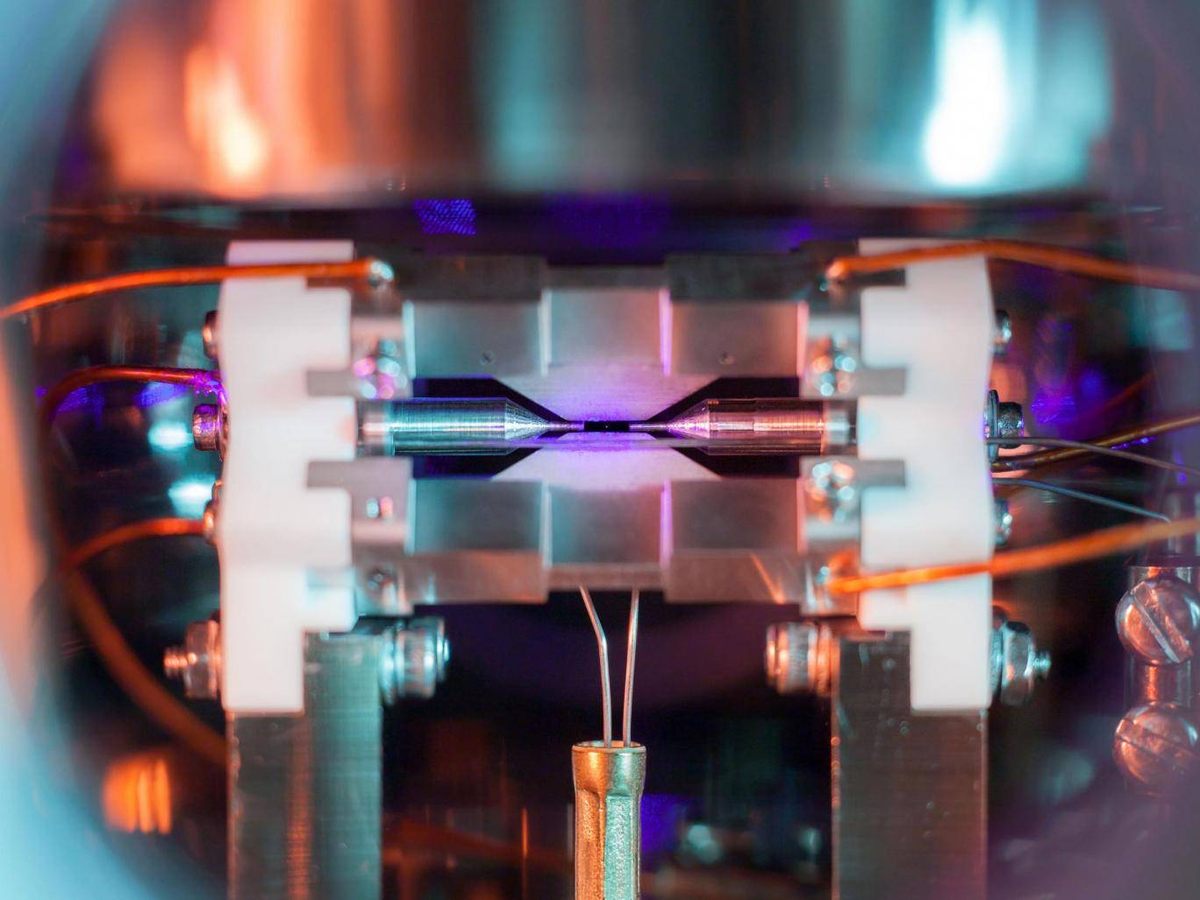

An Otherworldly Photograph of a Single Atom

It is suspended in the skinny gulf between two electrodes.

From the vantage point of an astronaut or a space-suited mannequin cruising the faraway skies in a Tesla, Earth is a speckled pebble—a pale blue dot. Other celestial bodies look that way to us, too: vague, impossibly small, endlessly intriguing. Consider the images beamed back from NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, which recently captured a smattering of stars and dwarf planets 3.79 billion miles away from Earth. “We’ve been able to make images farther from Earth than any spacecraft in history,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons’s principal investigator, in a statement. The grainy, pixelated pictures represent the distant reaches—they don’t show us much detail, but they push the frontier. They kindle curiosity about what’s (way, way) out there.

There’s no shortage of fascinating worlds and new perspectives to be found on terra firma, either. With feet firmly planted, there are plenty of ways to cast a gaze at the magnificent and vast or the astonishingly small. Atoms are among the most minute building blocks of everything around us, but may feel as obscure as a distant solar system. They’re difficult to picture, thanks in part to their mind-bending dimensions—they measure 0.1 nanometers in diameter, roughly a million times narrower than a single human hair. Though they’re home to a flurry of quantum activity, we rarely get a clear picture of it.

On a Sunday afternoon in August 2017, David Nadlinger, a physics researcher at the University of Oxford, set out to change that. He packed a Canon 5D Mark 11 and a tripod, and headed to the lab. By pointing the camera through a window of a vacuum chamber illuminated by a violet-hued laser, he was able to photograph a single positively charged strontium atom suspended in the two-millimeter gulf between two metal electrodes.

The image earned Nadlinger first prize in a recent science photography competition hosted by England’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). Any researchers who had received EPSRC funding for their work were eligible to enter. Nadlinger nabbed the grand title, besting more than 100 other entrants. Other finalists included a kaleidoscopic image of soap bubbles—crowned victorious in the the “Eureka and Discovery” category—and, courtesy of a Nanosurf Atomic Force Microscope, a zoomed-in look at the ridges underpinning a butterfly’s iridescent wing—deemed the most “Weird and Wonderful.”

Under Nadlinger’s lens, the atom is a pale dot, recalling that infamous image of our planet. “The idea of being able to see a single atom with the naked eye had struck me as a wonderfully direct and visceral bridge between the minuscule quantum world and our macroscopic reality,” he said in a statement. It’s a window into some of the smallest crannies of our own galaxy, where we might not always think to look.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook