Do Americans Sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’ Because of a Frat Party?

Or maybe it was the cigars that gave us this New Year’s Eve staple.

Guy Lombardo wasn’t thinking about tradition as the clock struck midnight in New York on New Year’s Eve 1929. He was probably thinking, as so many people were after the stock market crash that fall, about money.

In front of a crowd at the Roosevelt Hotel in Midtown Manhattan, Lombardo raised his violin bow and launched his 10-piece band, the Royal Canadians, into a sweet and soothing rendition of “Auld Lang Syne.”

The revelers on the sunken dance floor likely did not know the meaning of its Scots-language title. When the song went out over the radio waves in the first minutes of 1930, it was not yet a New Year’s Eve staple throughout the United States—and it may never have become one if not for a promised cigar company sponsorship and a raucous University of Virginia frat party.

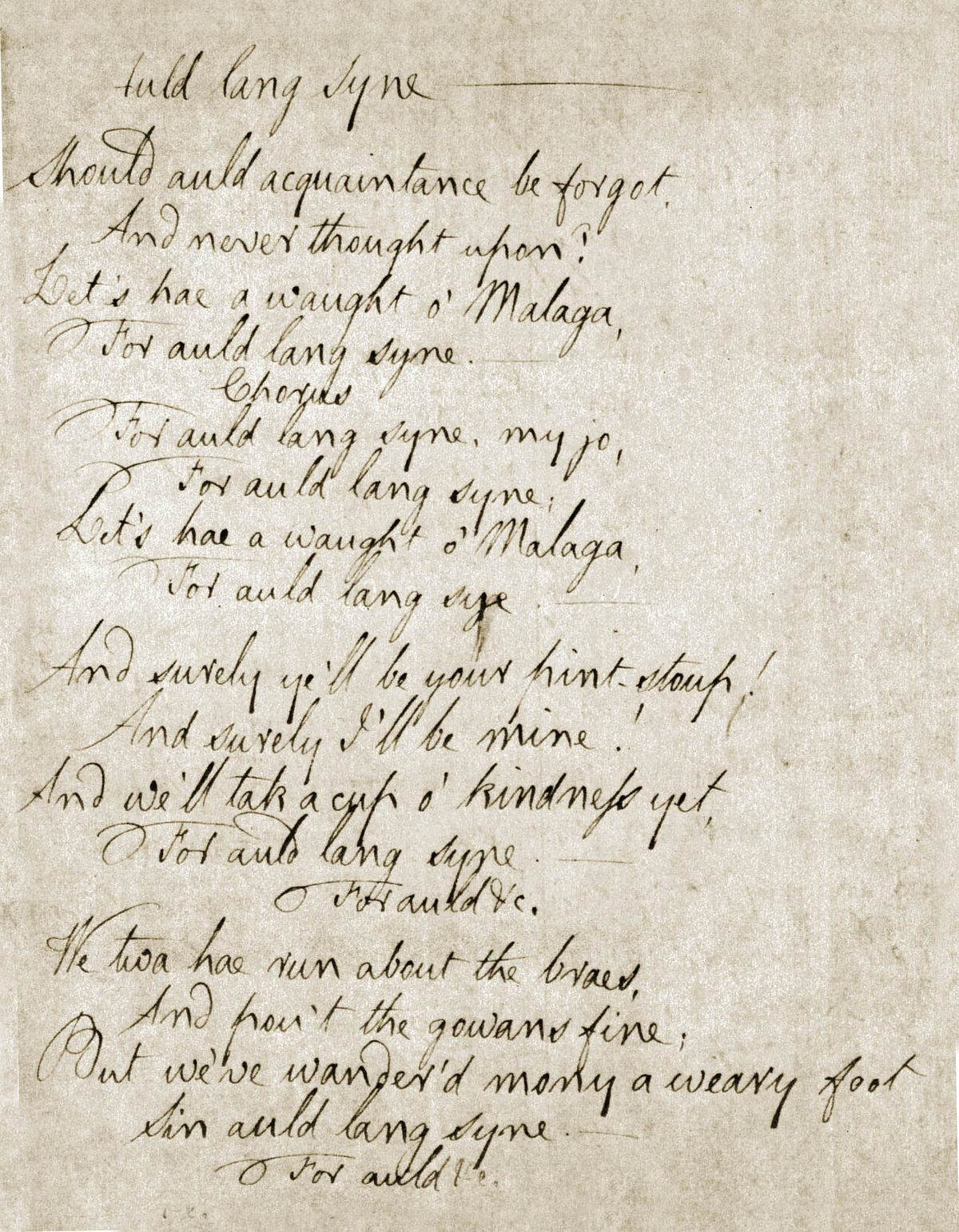

Lombardo didn’t “remember that first New Year’s Eve as anything special,” LIFE magazine later reported. “Auld Lang Syne” was already a standard in the Royal Canadians’ repertoire. The big band had gotten its start in southwestern Ontario, where Lombardo was raised, a region with a large population of Scottish immigrants who all knew “Auld Lang Syne.” The song—the modern lyrics of which are most commonly credited to 18th-century Scottish poet Robert Burns—was commonly sung in the old country when friends parted. (The title translates to “Old Long Since,” meaning something like “Since Long Ago.”)

“When we left Canada, we had no idea we’d ever play it again,” Lombardo said. In pursuit of fame, the band moved first to Chicago and then, just before the Great Crash on Black Thursday, to New York, where they had been promised a residency at the Roosevelt Hotel and a regular spot on a national radio program sponsored by a cigar brand—the Robert Burns Panatela show on CBS. Lombardo had already decided it would be fitting to end each radio broadcast with “Auld Lang Syne,” written by the poet with whom the skinny cigars shared a name. But the deal had yet to materialize. So Lombardo reached for the tune just as the band signed off from CBS, where it had been booked until midnight. As the ball dropped in Times Square, the band was actually heard on rival NBC, which picked up the Roosevelt feed.

And that might have been that—an old Scottish folk song, played by a Canadian band in a New York hotel late one night at the end of a tumultuous year. No one was thinking about the playlist for next New Year’s Eve. Lombardo and his bandmates had other things on their mind, mainly how to make a living as musicians in the first days of the Great Depression. The Roosevelt Hotel Grill Room where the band typically played was quiet most nights; few had the money to splurge on a weeknight outing and no one felt much like dancing.

But things were starting to look up for the band by around Easter 1930. They were playing regularly on the radio, which brought more people into the restaurant and earned the band numerous invitations to perform on college campuses. In April, they traveled to Charlottesville, home of the University of Virginia. “It’s funny how that college date remains in my memory,” Lombardo later wrote. It’s funny, too, how it contributed to an enduring American tradition.

The band was buoyed by the optimism they encountered on the college campus. After the formal dances—alcohol-free occasions—students often invited the men in the band back to fraternity parties. They brought along their instruments and “libations flowed freely,” Lombardo recalled. One night the band decided to end the evening with “Auld Lang Syne,” as they had so often in Ontario. We “were amazed by the reception it got from the students. They demanded one encore after another.” Finally, Lombardo leaned down from the bandstand to ask, “What’s so great about ‘Auld Lang Syne’?”

For the students, the answer was obvious: Lombardo was leading them in the school’s de facto fight song. “The Good Old Song” had the same tune as the Scottish standard, but instead of “Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and the days of auld lang syne,” the students heard “Let’s all join hands and give a yell for the dear old UVA.”

“We would always keep ‘Auld Lang Syne’ after that,” Lombardo wrote in his autobiography decades later. “The boys at Virginia had given us a reason to retain it.” By the time 1930 became 1931, the song was the band’s anthem—a joyous callback to those nights at the University of Virginia—and its signature signoff. At midnight, live from the Roosevelt Hotel, Lombardo, as he did most nights, led the Royal Canadians in “Auld Lang Syne.” He did the same for nearly half a century.

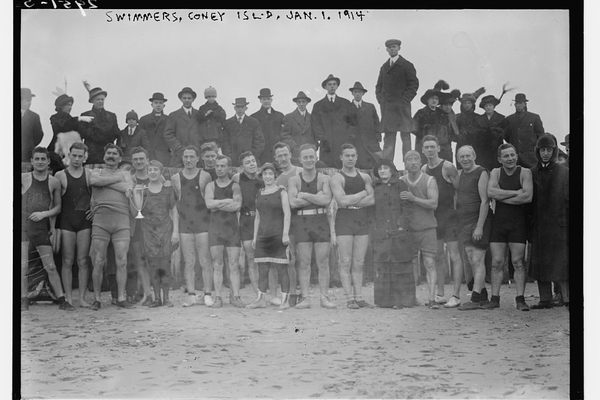

“I don’t really know if anybody sang ‘Auld Lang Syne’ on New Year’s Eve before we started playing it,” Lombardo would say in his later years. But in truth, some had. Lombardo would only have been the most famous man to play it at midnight in 1929, according to musicologist Morag Josephine Grant. As early as the 1880s, the song was sung as the clocks chimed in Scotland, and on New Year’s Eve 1890, the bells of the Metropolitan Church of the Trinity in lower Manhattan pealed with “Auld Lang Syne.” A crowd had gathered around the church, but “although hundreds listened, no one heard the tune of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ with which the New Year was welcomed,” The New York Times reported. The sounds of celebration drowned it out. But the none of the churches—and hotels and fraternal groups, among others—who celebrated midnight with “auld acquaintance” had the power to influence the whole of the country the way Guy Lombardo and the Royal Canadians could when broadcast coast to coast, first on the radio, and, by the late 1950s, on television.

“Should he and his Royal Canadians fail to play ‘Auld Lang Syne’ at midnight on New Year’s Eve at the Hotel Roosevelt Grill in New York, a deep uneasiness would run through a large segment of the American populace—a conviction that, despite the evidence on every calendar, the new year had not really arrived,” LIFE magazine wrote in 1965. By then, Lombardo’s mellow, saxophone-heavy sound was decidedly passé, which only made the solidity of the tradition he hadn’t meant to establish more pronounced. Lombardo was “Mr. New Year’s Eve” and midnight belonged to “Auld Lang Syne.”

In 1968, Lombardo joked on Laugh-In, “When I go, I’m taking New Year’s Eve with me.” Instead, after Lombardo’s death in November 1977, America collectively kept his memory alive. In the almost 100 years since the Royal Canadians first played their greatest lasting legacy at the stroke of midnight in Manhattan, countless other musicians have played the song—among them B.B. King, The Beach Boys, Prince, and Mariah Carey. But in the first minute of the first morning of 2022, the sound that echoed through Times Square was, once again, Guy Lombardo’s version of “Auld Lang Syne.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook