Bacardi’s Head Honcho Once Tried to Bomb Castro’s Cuba

After many a misadventure, his warplane is on display today.

Beverage companies can go to great lengths to keep their goods flowing, especially when they run afoul of international geopolitics. In the Soviet Union, Pepsi accepted payment for cola concentrate in warships that it could sell for scrap, leading to reams of jokes about the escalation of the Cola Wars. In the case of spirits-maker Bacardi, the company patriarch went much harder in his vendetta with the communist regime in Cuba. In 1962, he dreamed up a mission to bomb a Cuban oil refinery with a surplus warplane, a machine that aviation historians Dan Hagedorn and Leif Hellstrom call “very nearly the first corporate bomber in aviation history.”

Today, the Bacardi portfolio is large and easily recognizable—Grey Goose vodka, Patrón tequila, Bombay Sapphire gin, and more, in addition to its line of rums. But the company had humble roots. By the time Don Facundo Bacardí Massó started making rum in Cuba with a friend’s borrowed still in the 1860s, he had gone through a series of Job-like trials. A cholera epidemic had killed two of his children, and his general stores in and around Santiago had gone bankrupt. Making rum was a last-ditch shot at success, especially since at the time, according to booze historian Mark Spivak, the liquor “was almost universally regarded as a low-grade product, the favorite spirit of outlaws, social misfits, and lower classes.”

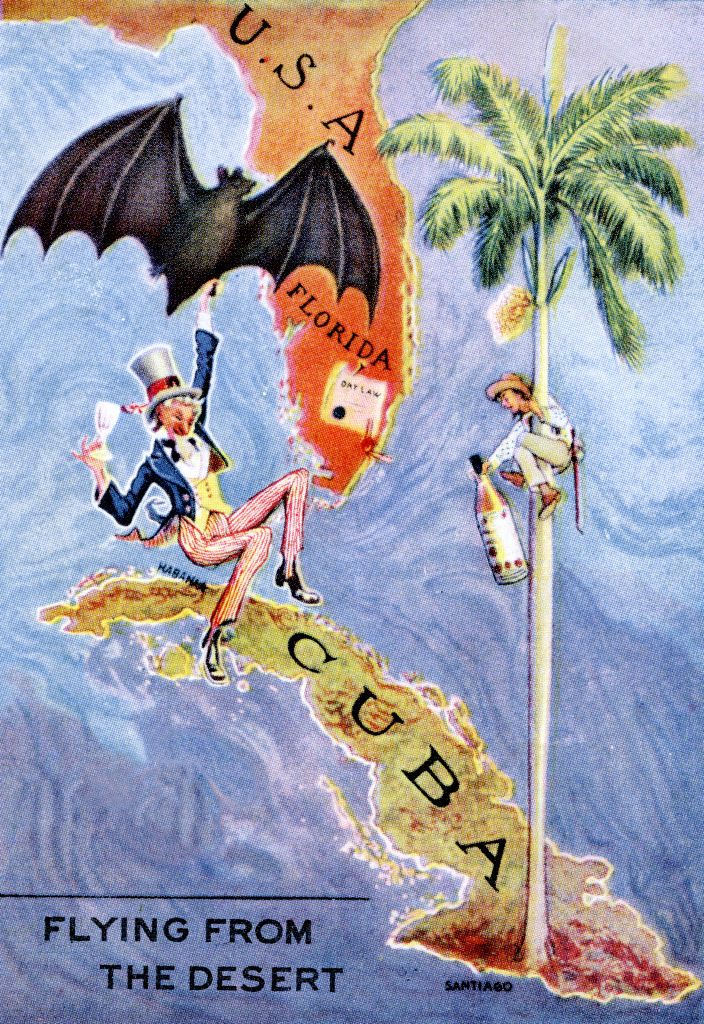

But as a 1963 article in The New York Times rhapsodized, Don Facundo “conjectured back in 1862 that there was a future in getting rum out of the peasant cantinas and off the waterfront into polite society.” He had the foresight to use a distinctive logo—the bat that still graces bottles and signaled even to illiterate drinkers that they were imbibing his creation. By the time he passed the business on to the next generation, the family was committed to what Spivak calls “unrelenting efforts to free Cuba from outside forces,” such as Spain and the United States. But the company’s greatest foe would come from within, when the revolution led by Fidel Castro banished Bacardi from its home.

It should have been impossible to separate Bacardi from Cuba. Henri Shueg, Don Facundo’s son-in-law, had inextricably tied the brand’s identity to the island, even as he opened distilleries abroad. Plus, Cuba had become a drinker’s paradise during Prohibition. Many a professional bartender, writes Spivak, moved to Cuba and found work in a sunny haven.

Also central to the brand’s identity, it seems, was the ardent political beliefs of the company’s lineage of presidents. Emilio Bacardi, Don Facundo’s son, went to jail several times for supporting and financing the country’s independence from Spain. Shueg, his successor, was less of a Cuban patriot, but next in line, his son-in-law, José “Pepín” Bosch, actually sent money to Fidel Castro as the revolutionary took on the corrupt Batista government. But at the same time, Bacardi quietly began to move essential parts of the business abroad, such as the yeast strain necessary for making its vaunted liquor.

Less than a year after Castro took over the Cuban government in 1960, his administration ordered large businesses nationalized. In 1962, as journalist Tom Gjelten writes in Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba, an exiled Bosch decided “to finance and organize a military action of his own in Cuba.”

It’s perhaps not as extreme a reaction as it might seem. After all, the United States had lent its support to Cuban exiles planning an attack on Cuba, resulting in 1961’s disastrous Bay of Pigs Invasion. But even without the explicit support of the United States, Bosch wanted to strike a fiery blow against his nemesis Castro. In their book Foreign Invaders: The Douglas Invader in Foreign Military and U.S. Clandestine Service, Hagedorn and Hellstrom note that one of the consuming goals of wealthy, exiled Cubans was to fight back, or “at the very least keep Castro in a high state of anxiety.”

In an interview with Gjelten, Pepín Bosch’s son Carlos related how the United States government kept shutting down his requests to start an air transport service (unrelated to Cuba and the liquor business) in 1962. Carlos was stunned to learn why, when his father offhandedly mentioned “the plane I’m keeping in Costa Rica.”

The plane in question was a Douglas B-26 Invader. With a wingspan of 70 feet, they were designed during World War II by Southern California–based Douglas Aircraft Company. Afterward, they were used by militaries worldwide. This particular bomber, a former U.S. Air Force plane from 1945, had spent its career in units based around the United States. Sold off as surplus in 1958, and it passed from owner to owner before a Miami-based insurance company purchased it in 1962, “quite likely acting on the instructions” of a lawyer connected with Bacardi, who had also contracted two Cuban pilots. The mission? To bomb a major oil refinery on the island, write Hagedorn and Hellstrom. Such a plan “would have arguably put Castro in very difficult circumstances, if successful,” destabilizing the country enough to perhaps even trigger a counterrevolution.

So on June 8, 1962, Gonzalo Herrera and Gustavo Ponzoa, both Bay of Pigs veterans, set off for Costa Rica with a fudged registration and a plan to carry out the bombing in July, after stocking up on bombs from Guatemala. The plan started to go south right away. The pilots landed at a beach at La Llorona in Costa Rica, but had to leave in a hurry when the tide came in while they waited in vain for their bomb supplier to show up. More misadventures followed, with both the Nicaraguan and Costa Rican governments circling, suspicious of the motives of the Cuban aviators and their unregistered American bomber.

Ponzoa even had the bad luck to run into his uncle, a Costa Rican official, who was rightfully leery of what his nephew was up to. It may have been that uncle who notified the U.S. government, leading to a visit from State Department agents, who told Herrera and Ponzoa to cease and desist. The pilots left the plane and made their way back to the United States, while Bosch turned to other Castro-defying plans, such as funding the exile group Representación Cubana del Exilio. The plane itself had a spirited second life, perhaps being used for smuggling in Costa Rica, and then flying officially as part of the Honduras Air Force. (Gjelten, in Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba, tells a slightly different story, naming a single pilot, Gaston Bernal, and stating that the CIA had been notified, rather than the State Department.)

“The Bacardi bomber” flew well into the 1970s, but it increasingly showed its age. The United States intelligence community wrote it off as a threat after a terrifying emergency landing in 1971, but it was rebuilt and shown off at events in Honduras until 1979. Painted broom handles were thrust into its nose to give the illusion that it was bristling with guns.

The Bacardi bomber did eventually return home to the United States, after it was purchased by pilot and plane engine–builder David Zeuschel. It eventually ended up in what is now called the USAF Airman Heritage Museum on Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, where it is still on display. Curator Fernando Cortez had never heard of the plane’s Bacardi connection, but he did confirm that the U.S. government had halted the aircraft’s mission to Cuba. “Once the CIA got word of the mission, they didn’t want World War III to start,” he says.

“In USAF colors, in honorable retirement,” Hagedorn and Hellstrom write, “44-35918 [the plane’s serial number] has come home at last.” But these days, the venerable plane is decorated with more than fake guns. A blonde pin-up, decked out in tropical fabric and flowers, sprawls across the aircraft’s nose, as an homage to one of the most famed B-26s of the Korean War. And next to her is painted the aircraft’s spot-on nickname: Versatile Lady.

You can join the conversation about this and other Spirits Week stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook