To Sweep Aside Drinking Regulations, Germans Hang Up Broomsticks

A unique tradition allows winemakers to host and serve customers in their homes.

As I wandered the cobbled streets of Untertürkheim, a wine-growing village, I passed colorful, half-timbered houses with pretty planter box-lined windows and hikers ambling up the steep stairways that pierce the vine-covered hills. But I stayed focused on my task: searching for a broomstick hanging over a doorway.

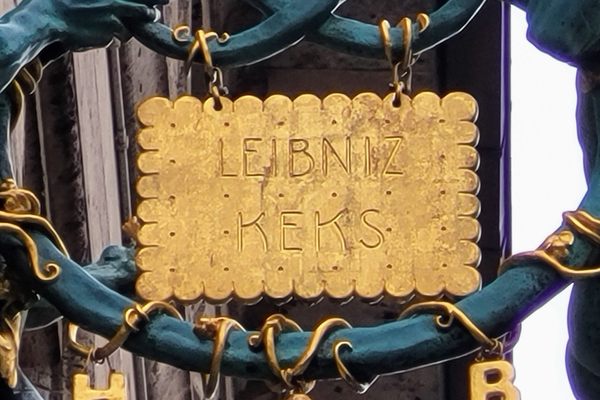

Here in southern Germany’s wine regions, a besen, or a broomstick, signifies something special. For up to 16 weeks, local laws permit winemakers to set up temporary restaurants to serve their latest harvest. So each year, typically in spring and fall, they sweep out their family room or barn, drag tables out from the garage, and recruit family members as servers. Then, they hang a broomstick outside to indicate they’re open.

These broomsticks inspired the name of these pop-up establishments: besenwirtschaften, or simply besens. The limited season creates demand, as does the feeling of being welcomed into a stranger’s home for a rowdy dinner party. As customers sidle up to each other at long communal tables, three-piece brass bands play catchy folk songs and wine is poured by the same hands that picked the grapes. It’s no wonder besen season is a local favorite.

This tradition of direct-to-consumer wine sales can be traced back 1,200 years. Allegedly it was Charlemagne who, in 812, issued Capitulare de villis vel curtis imperii, or A Chapter on Farmsteads of the Imperial Court, allowing winegrowers to sell any excess wine that was not delivered to the court. Winegrowers set up makeshift taverns in living rooms, barns, and cattle sheds, and hung ivy wreaths to indicate when they had wine for sale. It provided additional income and emptied the barrels before the next harvest.

The practice can still be found in many wine regions throughout Germany, albeit under different names. “In Rhineland, seasonal wine taverns are known as Straußwirtschaften, and they use wreaths to indicate they are open,” says Ernst Büscher from the German Wine Institute. “While in the Lake Constance region, the name Rädlewirtschaft is common and they display a wooden wagon wheel.”

Today, these seasonal taverns offer a vastly different dining experience to traditional restaurants. For starters, the wine is served in generous 250mL handled glasses, the food is cheap, and customers happily squeeze into long communal tables and snug booths. In lieu of menus (or QR codes), the day’s offerings are scribbled on a blackboard. The bill is tallied up on your coaster, and forget about paying with a credit card. Even the neon OPEN/CLOSED sign has been swept aside by the giant broomstick.

But behind this casual facade, besens need to follow strict rules.

“As well as only opening 16 weeks of the year, we can only serve wine we produce, juice, or water,” explains Steffi Schwarz, the third-generation manager of Schwarz Besen in Untertürkheim. “No beer and definitely no coffee.” The food must be simple, home-cooked fare, and only 40 customers are allowed at a time. “Oh and we need to hang a broom out the front to declare when we are open,” she adds.

As a trade-off, they are not classified as an official restaurant, thus avoiding the many financial and bureaucratic obligations that go with it.

And the broom? Its history is notoriously arcane.

“It might be because Swabians who live in Baden-Württemberg are quite fond of cleanliness,” laughs Büscher. While it’s not officially confirmed, the joke does have some substance. The rest of the country makes jokes about the local tradition of the Kehrwoche, or Sweeping Week, where each household in an apartment building takes turns to sweep the stairs and shovel the snow.

Nevertheless, the broom has become a local icon, welcoming customers in search of good cheervibes and great wine.

When I visited Schwarz Besen in December 2020, the vibe was like a rowdy family Christmas. In the low-ceilinged cellar of the family’s three-story house, where the wine production also takes place, drunk uncles gestured wildly at one end of the table, while cousins gossiped quietly at the other. Family photos hung on the wood-panelled walls.

“Most nights and often at lunchtime we are completely full,” says Schwarz. “Sometimes it’s standing room only.”

Due to the pandemic, Schwarz Besen and many other besens could not open in 2020, nor in early 2021. “During corona, these small wine producers suffered,” says Büscher. “They sell most of their wines just by opening their doors, and they don’t have [an alternative] distribution network.”

But after a long year, the doors at Rauscher Besen in Obertürkheim are finally open. Although when I visit on a chilly Thursday afternoon, the broomstick is nowhere to be seen.

“We had a huge storm this week and our broom fell down,” says Brigitte Rauscher, pointing to the oversized handmade broom nestled in the corner of the garden. Her father started the winery in 1967, running it until he passed away, and now her son and his partner head up operations.

I sip a chilled glass of Trollinger, a light fruity red that covers 60 percent of the region’s terraced hillside, and peruse the menu. Meat and potatoes dominate most dishes, while local Swabian dishes Käsepätzle (cheesy noodles), Maultaschen (large ravioli pasta squares), sausages and lentils with sauerkraut are crowd pleasers.

“Zum Wohl!” call my friendly table mates as we raise our glasses from a distance.

The Heislers, both in their seventies, have been coming to Rauscher Besen once or twice a week for more than 20 years. “We love it here. We love the company, the social atmosphere,” they explain in the local Swabian dialect. “We always meet new people, and the wine is great and the prices too.”

It’s this sociability that keeps people coming back to besens, and what ultimately made the Rauscher family decide to open for two short stints this summer, in between harvest, despite the challenges of the pandemic.

“Most people when they come in are strangers, but they leave as friends,” says Rauscher. “We really missed that during corona.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook