Living Bridges, Mechanical Dragons, and the Smell of Rain

The year in amazing arts and wondrous crafts.

In India, a village farmer weaves tree roots into bridges. In Italy, brothers cast bronze bells that can be heard around the world. In Israel, volunteers coax tractors back to life, while in Dallas, a team of mechanics returns historic trolleys to the tracks. What all of these artisans have in common is tradition; they are part of legacies that can stretch back decades or, in some cases, thousands of years. And they are part of the future, too, adapting their skills for a new era and passing along their knowledge to another generation. Hear our favorite stories of artists and craftspeople from 2023.

The Artisans Behind India’s Living Root Bridges

by Dania Rodrigues

For half a century, Hally War, a 68-year-old farmer from Siej village in northeastern India, has been growing a jingkieng jri—a living root bridge. These bridges come from the foundational myth of the Khasi tribe, and from Ficus elastica, a species of fig tree that thrives along the river banks there. War learned the art of weaving the tree roots into durable architectural marvels from his grandfather and has passed on the knowledge to his sons and grandsons. But elsewhere in the region, the skills required to preserve the living root bridge are disappearing.

The Last Days of Berlin’s Gas Streetlamps

by Alex Rennie

Gas lamps have been a part of Berlin’s landscape since they first lit Unter den Linden, the city’s central boulevard, in 1826. In the years before World War II, there were some 80,000 gas lamps in the city; today there are about 23,000—more than half the working gas street lamps in the world. But their light is fading. Since 2011, the German city has been working on converting the gas lights to LED alternatives, leaving conservationists feeling that Berlin is losing something with enormous cultural and practical value.

How Farmers Are Preserving Israel’s Disappearing Agricultural Legacy—One Tractor At a Time

by Gitit Ginat

Nestled in a hilly expanse of central Israel, among miles and miles of orange groves, an unusual museum is home to one of the world’s largest tractor collections—and a collective of more than 60 volunteers working to return the agricultural artifacts to working order. It’s a time-consuming but rewarding process, says founder Ezra Milstein. When an old tractor is finally restored, “we feel more important than doctors. We bring the dead back to life.”

The Italian Bells That Survived Nazis, Fires, and Even the Medieval Ages

by Asia London Palomba

Pasquale and Armando Marinelli are the 26th generation of a family who has been crafting handmade bells for around a millennium. “The same techniques and models, everything from A to Z, have been the same for the last 1,000 years,” says Armando. The family’s foundry is in an ancient town in southern Italy, but its bells are everywhere—peeling as far away as Easter Island and, maybe, one day even the Moon. “Why not?” asks Armando. “It’s only a matter of bureaucracy and a bit of luck.”

How Indian Perfumers Capture the Smell of Rain

by Zinara Rathnayke

Kannauj, a town in the northern India, is the only place in the world where perfumers know how to capture the enticing scent called mitti attar—“It’s the smell of the baked, parched earth when the first rains arrive after a long drought,” says Rajat Mehrotra, co-owner of the family-run Meena Perfumery. The process starts with the region’s clay. It ends with a fragrant liquid used in perfumes that sells for almost $9,000 a gallon.

Fixing the World’s Oldest Trolleys Is Like Solving a Century-Old Jigsaw Puzzle

by Greg Christensen

The Car Barn sits adjacent to a timeworn cemetery, tucked away from a cluster of upscale restaurants in the Uptown neighborhood of Dallas. This large warehouse is the maintenance garage for the city’s historic M-Line, perhaps the most eclectic operable collection of trolley cars, cobbled together from various countries and across decades. While other U.S. cities still run their own historic cars today, Dallas’s Car Barn is one of the few places where the antiquated mechanisms can be restored, thanks to the specific and wide-ranging historical knowledge of its mechanics.

How to Maintain Your Dragon

by Claire Naylor

As you arrive by ferry in the port city of Calais, France, you may spot people riding on the back of a 39-foot-tall, fire-breathing creature that’s creeping along the waterfront. Part sculpture, part machine, part puppet, the Calais Dragon has become a beloved piece of interactive street theater—but its charming performances require the devotion of an entire entourage, including eight “dragon lords” who pilot the beast in teams of four; three “veterinarians” to monitor of its onboard computer; 48 batteries; countless pumps, valves, and yards of wiring; and a daily feeding of “strawberry syrup” (red diesel).

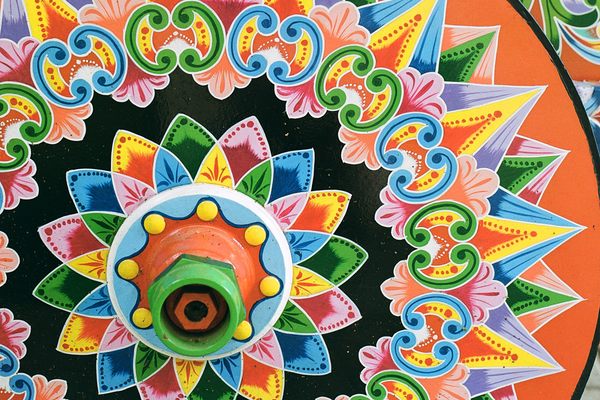

A Look Inside the Last Colorful Oxcart Factory in Costa Rica

by Sarah Yeoman

Oxcarts were once a common sight in Central America, but in only Costa Rica were the utilitarian transportation devices, commonly used to carry coffee beans from the mountains to the coasts, turned into colorful works of art. Many of these unique carts were created in Sarchí, where Fabrica de Carretas Eloy Alfaro is now the last remaining factory in the country manufacturing elaborate oxcarts for distribution.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook