U.S. Museums Hold the Remains of Thousands of Black People

Cadavers from marginalized communities have been co-opted for collections since the 1700s.

This story was originally published in The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

Among the human remains in Harvard University’s museum collections are those of 15 people who were probably enslaved African American people. Earlier this year, the school announced a new committee that will conduct a comprehensive survey of Harvard’s collections, develop new policies, and propose ways to memorialize and repatriate the remains.

“We must begin to confront the reality of a past in which academic curiosity and opportunity overwhelmed humanity,” wrote Harvard President Lawrence S. Bacow.

This dehumanizing history of collecting African American bodies as scientific specimens is not a problem just at Harvard. Last year, the University of Pennsylvania announced that its anthropology museum will address the legacy of the 1,300 human skulls—including those of 55 enslaved people from Cuba and the U.S.—in its collection, which was historically used to denigrate the intelligence and character of Black people and Native Americans.

Other institutions have far more Black skeletons in their closets. By one estimate, the Smithsonian Institution, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and Howard University hold the remains of some 2,000 African Americans among them. The total only increases when considering museums with remains from other populations across the African diaspora. How many more sets of remains lie in museum storerooms across the United States, and whether or not they were collected with consent, is unknown.

As archaeologists, we understand the impulse to gather human remains to tell our human story. Osteobiographies, life histories constructed from skeletal remains, can offer insights into nutritional, migratory, pathological, and even political-economic conditions of past populations. However, scholars and activists across the U.S. are now seeking to recognize and redress the deep history of violence against Black bodies. Museums and society are finally confronting how the desires of science have at times eclipsed the demands of human rights.

How did the remains of so many Black people end up in collections, and what can be done about it?

Collecting Black bodies

The abuse and circulation of African American human remains for research dates back at least to 1763, with the dissection of corpses of the enslaved for the first anatomy lecture in the American Colonies.

The systematic collection of African American remains, as well as those of people from other marginalized communities, began with the work of Samuel George Morton. Considered the founder of American physical anthropology, Morton professionalized the acquisition of human remains in the name of scientific practice and education.

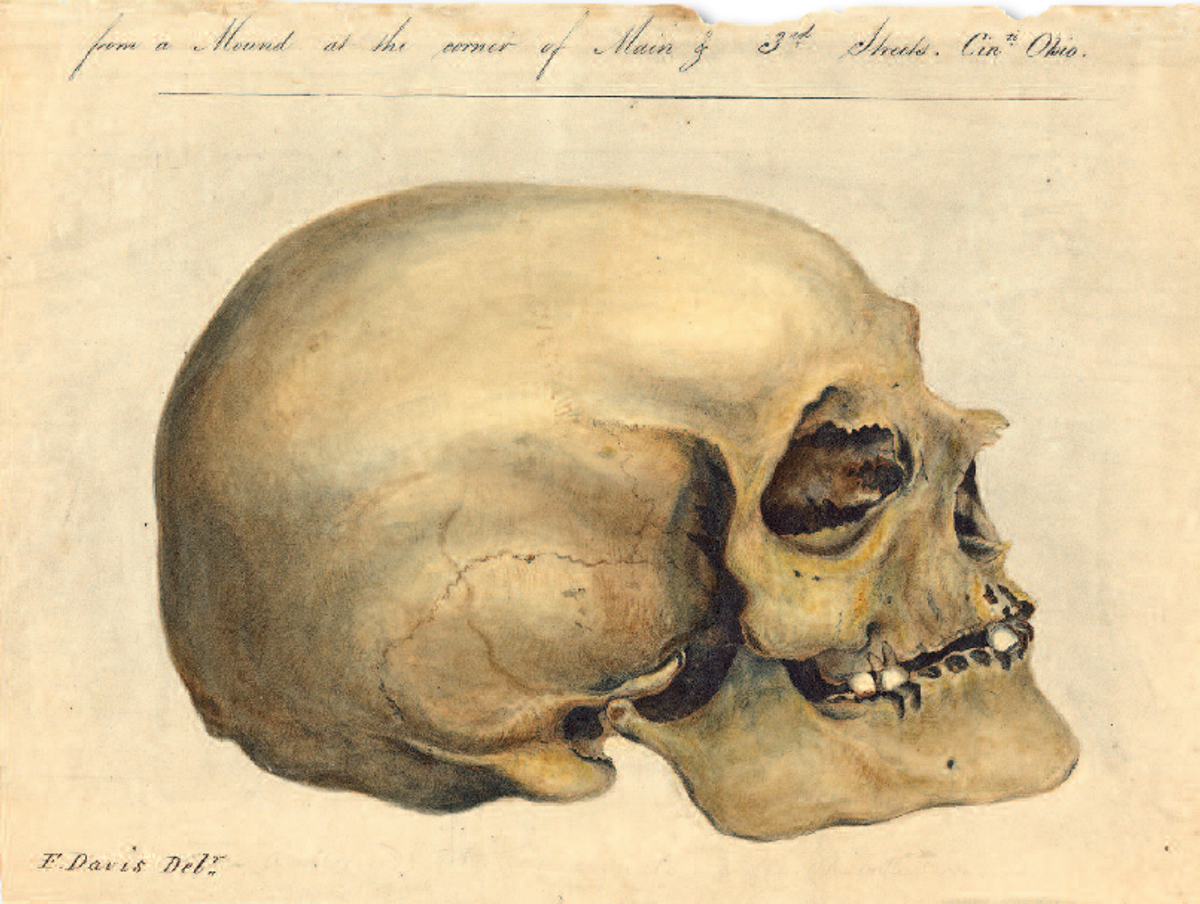

Morton boasted the first collection of human remains, at one point considered to be the largest globally. He used its subjects-turned-specimens to promote racist hierarchies through pseudoscientific interpretations of cranial measurements. His research resulted in his 1839 magnum opus, Crania Americana, replete with hundreds of hand-drawn images of skulls and faulty-logic racial categorization.

His collection eventually ended up at the University of Pennsylvania. Only last year did the university officially announce the collection had been removed from a shelved display within an archaeology classroom.

The impact of Morton’s collection and career ricocheted far and wide, laying the foundation for unethical practices built on the theft, transportation, and accumulation of human remains—especially of those most marginalized. Collecting surged during the time of the Civil War. From the late 19th century well into the 20th, skeletal collections in museums across the country skyrocketed.

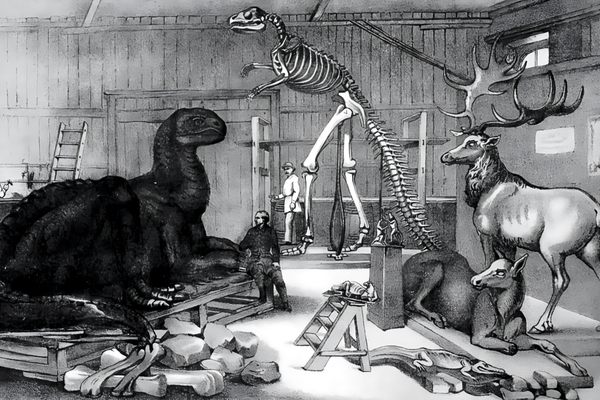

Morton also influenced the ideology of biologist Louis Agassiz, his eventual collaborator. Agassiz founded Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, which originally bore his name. His own collection practices around the photographed bodies of the enslaved have embroiled the university in a public lawsuit.

Institutions long embraced such collections primarily for the pseudoscientific work of justifying racial hierarchies. But they also enhanced their prestige by the number of remains in their collections that could be used for research as well as for exhibitions that fed the public’s morbid curiosity.

Eventually, most collecting institutions shifted away from these original goals but held on to human remains for teaching skeletal biology and testing new scientific methods. A majority of museum collections, however, sit unused, retained in the belief that they may help answer questions at some point in the future.

Ultimately, the remains of African American people, freed or enslaved, are in these collections because the captivity of their bodies, both living and deceased, was the very foundation of museums of medicine, anthropology, archaeology, natural history, and more. While some academic and cultural institutions have taken the initiative to confront their legacies with slavery—such as decolonization efforts to include more diverse perspectives and values—a national effort has yet to take shape.

Desecrated in life and death

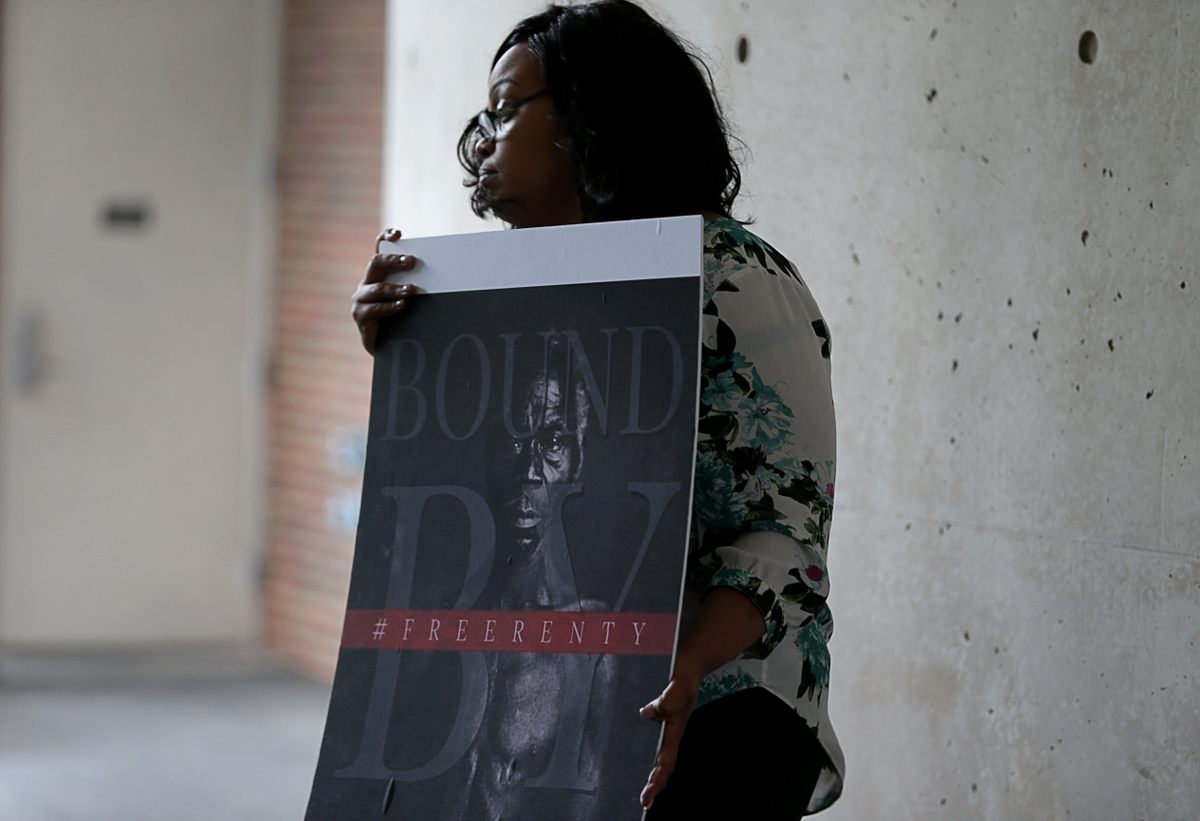

The U.S. Senate passed the African American Burial Grounds Network Act in December 2020. This bill would establish a voluntary network to identify and protect often at-risk African American cemeteries. The program would be administered through the National Park Service, and nothing in the legislation would apply to private property without the consent of landowners. More than 50 prominent national, state, and local organizations support the passage of the act into law and are working to have it reintroduced in Congress’s current session.

But even this legislation does not include the remains of Black people in museum collections. Such an addition would be more in line with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a 1990 federal law that addresses Native American human remains in all contexts—both in the ground and in collections. This work is necessary because many of the remains of Black people, like those of Native Americans, were taken without the consent of family, used in ways that contravened spiritual traditions, and treated with less respect than most others in society.

In the absence of such an addition, the work of finding all of the African American remains in museums will be unorganized and inconsistent. Institutions will need to make efforts on their own, which will cost more money and consume more resources. Even more importantly, the absence of a coordinated, national effort will mean the delay of justice for thousands of African American ancestors whose bodies have been, and continue to be, desecrated.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook