A New Crusade

How the mysterious, millennium-old, stateless Order of Malta outlived its contemporaries and established a place in the modern Middle East.

In a dimly lit room in northern Lebanon, a metal twin bed frame sat pushed against a window. Ghadire Abdelrahman, propped up by a heap of pillows, was silhouetted by the sun outside. The 26-year-old’s leg lay painfully stretched off the bed, a swollen foot wrapped tight in bandages. Next to the road outside, a blue sign indicated “Syrian borders” with an arrow. The nearest border checkpoint was a 10-minute drive away. “At least you don’t hear bombing,” she said.

Beyond the sign, a line of low green hills spanned the horizon, marking the end of Lebanon’s northernmost district, Akkar. On the other side lay the Syrian governorate of Homs. In fuzzy border areas like this one, some Lebanese people speak Arabic with Syrian accents. Syrians and Lebanese intermarry, with personal and political ties dating back to Ottoman times. The border crossing in Akkar, nicknamed the “Gateway to Syria,” served as a main route for cargo trucks. People living at the border, an area known for its limited infrastructure, would rather drive to the city of Homs than the more distant Beirut to browse shops. Relations between the two countries have always been fraught and sometimes violent, but the neighbors have, on and off, kept fluid boundaries.

As the civil war erupted, grew, and persisted, more than half of Syria’s population was displaced, either internally or across borders, including the people—some 1.5 million in total—who began streaming into Lebanon. Commercial trade routes were strangled. In their place, contraband operations smuggled weapons, supplies, and even soldiers across the border through Akkar—a Sunni-majority area, like Syria, in religiously diverse Lebanon—to shore up opposition to the Assad regime (though Lebanon’s Shia Islamist political party and militant group Hezbollah supports Assad). In the other direction, refugees fled bombings and attacks. They came via both official and unofficial channels, many empty-handed save the clothes on their backs.

Before the war, Ghadire and her sister, 28-year-old Munira, lived with their widowed mother in the border village of Al-Hosn, which rebels occupied in 2011. They had an old stone house with its own olive grove, and a little vegetable garden where they grew cucumbers and tomatoes. After the revolt, the Syrian military retaliated with an embargo, followed by kidnappings and disappearances. After their cousin was killed in a street bombing, Ghadire’s family fled to Damascus. By then the fighting had escalated. They spent eight months in a settlement for displaced people. Rebels approached, warplanes whizzed overhead, supplies dwindled. “People started eating grass and anything they could find,” said Munira.

Many Syrians had already left, but Ghadire and her family instead went back north to Homs, where they were able to rent a small house. Steady bombardments became routine. Through them all, Ghadire took classes in chemistry. Munira got a degree in Arabic literature. Years passed. Then, in July 2016, Ghadire was studying late one Ramadan night when a bomb blast slammed her backward and shattered both her legs. No one knew who dropped it. “I came in to help her,” said Munira, who carried her unconscious sister to the nearest hospital, “I thought she was dead.”

Hospitals in Homs had been targeted in attacks since the start of the war, and medical workers treating patients risked government detention—or worse. The beleaguered doctors still did what they could to keep Ghadire alive. “They put a cast on my leg, but I needed an operation. They wrapped my hip, but I needed treatment,” she explained.

Meanwhile, the influx of refugees into Lebanon slowed as parts of Syria were declared safe. Tens of thousands of Syrians, spurred by the Lebanese government, even began crossing back. This past winter, Ghadire set out against the trickle of returnees. Aided by an uncle living there, and plagued by constant, now years-long pain, she arrived, unregistered, in Lebanon. She came to neglected Akkar, afflicted with Lebanon’s highest poverty rates, in search of medical care—a reason that might have been unthinkable before.

Her mother and sister followed a month later. Once a short drive, the trip took over 24 hours in a series of choreographed rides. Akkar still suffers from a lack of medical services, but it is a staging ground for the Order of Malta—a nearly-1,000-year-old Christian chivalric order that pre-dates the dawn of the Crusades. There, the Order operates Mobile Medical Units (MMUs), roving, retrofitted minibuses staffed with local doctors and nurses, that serve as treatment rooms, consultation spaces, and medical dispensaries.

“Imagine me, living under bombs with fear in my gut all day, in the worst conditions possible,” said Ghadire, who relied on strong painkillers in Homs, and is still mostly unable to walk. Through the Order, Ghadire has received medical scans, physical therapy sessions, and a pain management plan. Mingling with other Syrian refugees over the course of her visits, she said, “I saw worse cases than my own.” Energized, she sat up in the bed, wearing a wine-colored jumpsuit, her hijab covered in dusky rose blossoms. “This helped me get out of my depression.” Outside the window, the hilly borderland loomed—still reachable, but now half a world away.

“We’re living,” said her sister Munira. “Because we’re not dead.”

The Order of Malta seems like an anachronism in the 21st century. A contemporary of the Teutonic Order and the Knights Templar, it was recognized as an extraterritorial Catholic sovereignty in 1113 by Pope Paschal II. There are more than 13,000 members spread between continents, still known in medieval-era parlance as “knights” and “dames.” Most are lay members and, according to experts on its history, the Order has always been strictly non-proselytizing, but the highest echelons of membership—Knights of Justice and Professed Conventual Chaplains—must adopt monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Protected for centuries under the pope, the Order of Malta remains independent. Lacking any fixed territory beyond a pair of administrative headquarters in Rome, it is both global and spectral, with its own government and constitution. It maintains diplomatic relations with more than 100 countries and has outposts around the world, from Berlin to Bamako. Like Palestine, the Order has a permanent observer status at the United Nations. Members on diplomatic missions can even travel with Order of Malta passports.

Sovereign and independent, but without borders of its own, the organization has developed a quirky geopolitical agility. Its relief agency, Malteser International, has a far-reaching humanitarian portfolio, bringing, it states, the “balm of Christian charity” to 120 countries. Also known as the Knights or Hospitallers of Malta, the Order has a global staff of some 42,000—mostly medical personnel, from a range of religions—and almost twice that many volunteers. There are national associations empowered to set their own humanitarian agendas, and no central, governing authority for these programs. The Order’s staff has provided disaster relief after typhoons, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions, as well as care for people afflicted with ebola or leprosy in West Africa and Southeast Asia, and operates specialized dementia facilities in the United Kingdom, Germany, and France.

In medieval and early modern times, and even into the 20th century, members were culled from Europe’s noble families. Membership is still invitation-only and new recruits must be sponsored by existing members, but the emphasis, the Order states, is on “nobility of spirit” rather than aristocratic roots. Their aid budget comes from private donations and members, although the Order’s healthcare programs often receive financing from national governments. Membership is global, but the highest concentration is in Western and Southern Europe. National associations are empowered to set their own humanitarian and medical care agendas.

A cornerstone of the Order’s relief and diplomacy work takes place in border zones—places that are often off-limits to traditional state actors. Hypermobile by choice and by tradition, they serve populations who are themselves mobile as a desperate consequence of war, natural disaster, or upheaval. At the Turkish-Syrian border, the Order runs a field hospital for refugees. They are facilitating resettlement for Yazidi populations in Iraq. Medical teams joined Italian ships to assist migrants at sea (until Italy’s right-wing government closed their ports). As a diplomatic entity, they only work publicly, visibly, and in partnership with governments, but the Order’s reach is such that roughly half of all new refugees in Germany in 2014, for example, received aid from them.

In Lebanon, the Order operates four MMUs, which patrol the country’s remote, neglected areas and act as satellites to nine brick-and-mortar health centers. They were first deployed in southern Lebanon, after the 2006 war between Israeli and Hezbollah forces. During that conflict, the Order’s local healthcare center had its windows and doors blown out and stayed shut for 33 days. But patients still picked through the broken glass at night to fill their prescriptions—and kept a log of their own to indicate who had taken what.

“Sometimes you’re there because no one else is there,” says Ghade El-Zein, Director of Health and Social Services at the Tyre-based Imam Sadr Foundation, named for a famed Shia reformer who disappeared during a trip to Libya in 1978. The foundation collaborated with the Order to comanage the MMUs. “When we can move,” she adds, “we move.”

In a quiet village in Akkar, not far from where Ghadire was recovering, a long line gathered at midday in front of the MMU, a white, modern minibus with windows discreetly covered and the symbol of the Order—a red shield with a white, eight-pointed Maltese cross—on the side. In the air-conditioned bus, a feverish nine-month-old baby lay fitfully on a padded examination table. “I come here very often,” sighed his mother. “I have six kids, so each takes their turn getting sick.” A man in chipped eyeglasses handed the doctor a lab report he had brought with him. Another man carried an eight-year-old boy with a fractured ankle through the door.

In line was a Syrian woman in her 60s. In her hometown of Talbiseh, she spent every night for a full year in a cellar, escaping bombing. Then she began having difficulty breathing. After coming by bus to Lebanon six years ago, she learned that she had a blocked artery and required surgery. After the operation, phone calls to her home in Syria, where her husband stayed behind, went unanswered. “I’m afraid of going back,” she said. “I don’t know what I’ll find there.”

“I didn’t know there were even people like this, who spend their lives in such misery,” said the doctor, 70-year-old Abdallah Khoury. “If we didn’t exist, what would these people do?” He began to examine the boy with the broken ankle, and then held up a stethoscope to listen to his lungs. “This is an asthmatic family,” he explained. Though Khoury sees hundreds of patients, he recalls many of their medical histories by sight. “I like to stay in my bus,” he added, “and listen to the lives of people.”

In its earliest incarnation, the Order of Malta was dedicated to the care of the sick and poor, then it took up arms to defend Christian territories in the Holy Land, before reverting back to its original mission, many centuries later. Lebanon has the largest proportion of Christians among Middle Eastern countries—roughly 40 percent—but a century ago, there were twice as many. Active in Lebanon since 1957, the Order still works to safeguard Christian interests, but—in a move that might seem paradoxical—only through strictly interfaith charity work. “Our culture here in this region has always been a culture of living together,” explains Oumayma Farah, General Delegate of the Order’s Lebanese Association. “The idea was not to serve Christian minorities but to serve everyone, and to empower Christian minorities to stay in their land.” She adds, “One day, when the Syrians go back to their homes, the MMU can go back with them.”

In 1985, the same year that the Order of Malta began its collaboration with the Imam Sadr Foundation, the body of a Dutch priest, 44-year-old Nicolas Kluiters, was found in a ditch in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. It was a decade into the country’s 15-year civil war. In response, the Order of Malta made the decision to construct a new medical center there. “Any sensible person would think it’s too dangerous,” says Farah. “We thought, this is where we have to be to respond to our mission.” The Order partnered with a local Sunni humanitarian organization to bolster support. “They told us, you are crazy to go there,” says Farah. “But one thing our faith tells us is not to be afraid.”

Order of Malta staff spent months gaining trust there, and eventually the center became a refuge, where Muslims and Christians gathered for medical and psychological support. But criss-crossed for centuries by fighters and fortune-seekers, missionaries and mercenaries, sages and sultans, the Levant and its turbulent histories cast long shadows. During the first uncertain months, the Order took a precaution. It kept its emblem—a relic from its medieval association with the Republic of Amalfi in Italy—hidden. “It’s still a cross. You’re in a very sensitive area,” explains Farah. For many, there were still boundaries. “For them,” she adds, “the knights are always the Crusaders.”

Leafy, church-filled Aventino is one of the seven hills of Rome, and home to one of the city’s more cryptic attractions: the Aventine Keyhole. The tiny, bullet hole–shaped opening in an otherwise unremarkable green door is hidden by an omnipresent queue of tourists, off their idling Segways and jostling for a peek inside. Through the hole, designed by the artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi in the 18th century, one can see a tiny, zoomed-in view of St. Peter’s Basilica, two miles away, perfectly framed by laurel trees. The experience captures three sovereignties in one field of vision: Italy, the Holy See, and the Order of Malta.

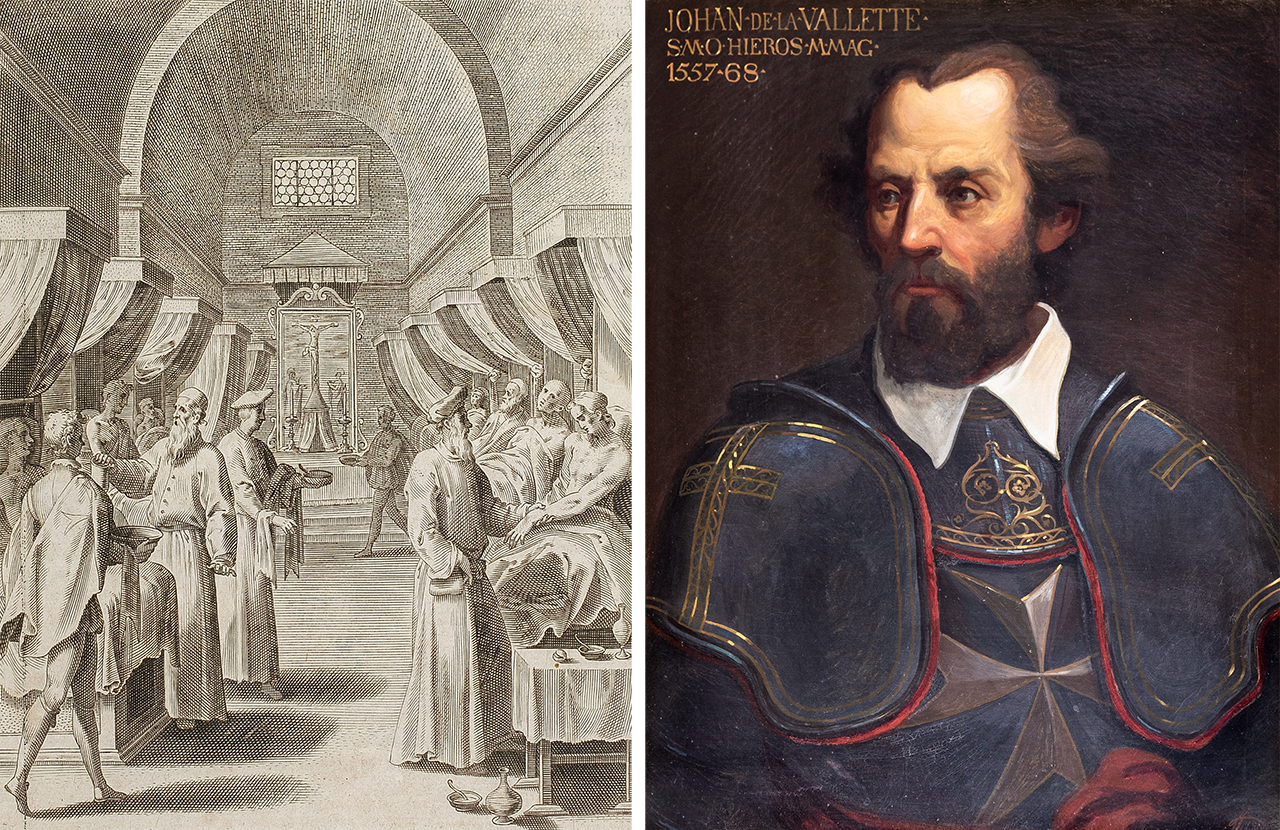

The green door is the entrance to an old hilltop priory that serves as the extraterritorial headquarters of the globetrotting knights. After their defeat in the Holy Land centuries before, and before they settled in Rome in 1834, the Order controlled the island of Rhodes and then Malta, reflected in their mouthful of an official name: the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta. Behind the green door, a sprawling, sun-drenched garden with carefully cubed hedges leads to the Magistral Villa, where the Grand Masters of the Order are elected in clandestine meetings similar to papal conclaves. Leaders, who should be over 50 or have 10 years of the necessary experience, are selected from the Order’s knights and serve life terms. (British-born Grand Master Matthew Festing resigned in 2017 following a dispute over the distribution of condoms—as revealed by Wikileaks.)

In the ornate, chandeliered Chapter General Room, portraits of the 78 deceased Grand Masters hang in rows, beginning with the Blessed Gerard, an 11th-century leader who traveled to Jerusalem to found the Hospitallers’ first monastic hospital. Christian eschatology has infused the gallery. “People say that when the wall space runs out, that will be the end of the world—the apocalypse,” says Valérie Guillot, who coordinates guided tours, available only on Friday and Saturday mornings. There is currently room for a dozen or so more paintings.

The Aventino compound once belonged to the Knights Templar. After the militaristic Christian knights were dissolved in the early 14th century, the Order of Malta inherited their contemporaries’ properties, along with their duty to defend Latin Christendom, as detailed in the book The Knights Hospitaller by the medieval historian Helen Nicholson—one of many monographs shelved in the Order’s magistral archives in Rome. Once known for their care of the poor and sick in Jerusalem and then Acre, the Hospitallers participated in multiple campaigns at the front line of the Crusades, advancing the Church’s interests along battle-scarred Christian-Muslim borders. Pope Honorius III extolled the Order’s militarization, praising the fighters, Nicholson’s history explains, as “defenders of the orthodox Christian faith, their hearts inflamed with the fire of the Holy Spirit.”

In another gallery in the villa hangs 17th-century oil paintings depicting fierce naval skirmishes, primarily with Ottomans and North African corsairs. After the Order of Malta seized control of Rhodes in the early 13th century—ousted just two centuries later by Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent—they established a naval league and earned a reputation as skilled mariners. Aspiring knights were selected from noble families and underwent four tours of duty at sea, each lasting half a year, known as “caravans.” These included raids on Muslim ports and ships, with the knights-in-training acting more like buccaneers.

“They created a very particular image of themselves which might be bizarre,” says Emanuel Buttigieg, a historian at the University of Malta, through the dual functions of fighting and nursing. But both were perceived as sacred duties. Unlike the Templars, who proudly trumpeted their military prowess, the Order “kept a lower profile,” simultaneously continuing work as interfaith healers. That’s one reason a holdover from medieval Christendom kept swinging, through the Renaissance, the Age of Discovery, the Enlightenment—and beyond. “The reason that the Hospitallers survived is that they were a bit more canny about how they presented themselves,” says Buttigieg.

From 1530 to 1798, the Order had its seat of power in Malta. Jean de Valette, 16th-century Grand Master of the Order, founded the island’s capital, still called Valletta, following the dramatic Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565. The armed Hospitallers clashed with Ottomans and Mamluks, whose rivalries the Order capitalized on, according to Buttigieg. Both sides captured a reserve of slaves to serve as free labor. But the idea of a clash of civilizations—Christendom versus Islam—“simplif[ies] what is a much more complex and interesting picture,” the historian says. Despite the Order’s long-held opposition to Islam, more nuanced relations emerged across the fractious Mediterranean. In the 1750s, when Sicily launched an embargo on Malta, Tunisians, who wished to assert their autonomy from their distant Ottoman masters, stepped in to provide a supply of meat.

At the turn of the eighteenth century, Napoleon Bonaparte and French revolutionary forces invaded Malta, plundering the island’s churches. The Hospitallers retreated into an amorphous, ignominious exile. Pope Gregory XVI allowed the Order to move to Rome a few decades later, coinciding with a push for the now-landless Order to rededicate itself solely to its original medical, humanitarian mission. During World War I, they established ambulatory clinics aboard moving trains—precursors to the modern MMUs.

Despite their modern humanitarian reputation, the Order is still—through its longevity and perceived secrecy—the subject of a number of conspiracy theories. These can involve, at times, Satan, Freemasons, or JFK—and, more recently, American foreign policy in the Middle East. In 2007, a widely reported op-ed in the Dubai-based daily al-Bayan, written by a member of the Jordanian parliament, urged readers to attack the Order’s Cairo embassy. Under the headline “The Knights of Malta—more than a conspiracy,” and referring to the Order as “the most mysterious government in the world,” their piece linked its charitable missions to the George W. Bush administration’s evangelist-inflected military campaigns. Several years later, the Pulitzer-winning investigative journalist Seymour Hersh accused top-ranking U.S. officers in Afghanistan and Iraq, among them General Stanley A. McChrystal, as being members or supporters of the Order of Malta, which both McChrystal and the Order have denied.

The Hospitallers, going back centuries, have always had a particular focus on aiding populations on the move, from pilgrims to refugees. But, according to Grand Chancellor of the Order of Malta, H.E. Albrecht Freiherr von Boeselager—also a Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion in Obedience—its Catholic-inspired charitable mission “is not normally carried out in weapons.” While it once chased Muslim armies and others from Christian-patrolled lands and waters, the Order now aids safe passage. Working across continents, says Buttigieg, “has given the Order this feeling that it’s an organization that is beyond borders—that it is there to serve people, irrespective of borders.” This is a far cry from past centuries, when, from hard-won strongholds in the Levant and along the Mediterranean coasts, the Order “was also about making war across borders,” Buttigieg says.

The mandatory training for knights, known as caravans, still exists, but has been repurposed to refer to a 10-month volunteer program in Lebanon. From autumn to early summer each year, German and Lebanese youth delegates tend to the disabled during daily visits to group homes and psychiatric wards. On one recent beauty-themed session in a women’s facility in the mountains, German caravan volunteers brought along nail polish. Patients are still referred to as “Lords,” a distinctive fusion of devotion and humanitarian work. But the Order’s landscape of loyalties has shifted—and softened. “I think we survived a thousand years,” von Boeselager muses, “because the Order was always able to adapt.”

The Ramadan-deserted streets radiated with furnace-like heat. A woman in a black abaya hung a carpet in the sun, then darted back into her house. A chipper weather report on the radio promised “températures effrayantes,” frightening temperatures. But on looming mountaintops in the distance, patches of snow glittered incongruously. Rising from the plains of eastern Bekaa Valley, which runs like a scar through the middle of Lebanon, is Mount Hermon, at 9,232 feet. It straddles Lebanon and Syria, part of the highlands that include the Golan Heights, which were seized in 1967 from Syria by Israel. Recently a controversial new settlement was inaugurated there: Trump Heights.

An energetic and gregarious doctor, 62-year-old Jamal Ismael, head doctor of the Bekaa Valley MMU, was out making his rounds. The MMU was parked that day in the village of Aakaba, where people belong to the distinctive Druze ethno-religious group. Its arrival is usually announced by both mosque and church loudspeakers. Ismael entered the van and instantly began bantering with patients, who gathered to shake his hand. He chided one older woman for not taking her diabetes medication: “You have to take the medicine. You have to.” Nurses thumbed through a reserve of canary-yellow folders stocked with patient histories. A pair of sisters came in, each with hormonal imbalances—one dressed in the traditional black robe and long white veil of the Druze faith, the other in hot pink sneakers and acid-washed jeans. “That’s the freedom of the Druze,” Ismael remarked cheerfully.

Another Order of Malta patient, 45-year-old Sabah Daoub, lives with three of her six children behind an abandoned storefront in town, wedged between a gas station and a kanafeh shop—one of many belly-up businesses rented out to house refugees. When the family arrived from Syria six years ago, Daoub sought out treatment for her traumatized son, Mohammad, who was stricken with fever. Years later, he still suffers from recurrent nightmares and visits an Order of Malta psychologist. “They told me it’s normal. He’s been through a lot,” Daoub said. “Even when someone sets off a firecracker, he panics.”

Just 139 miles long and 35 miles wide on average, present-day Lebanon is the product of a 19th-century, European-born cultural imaginary: the modern nation-state. Once part of a great swathe of the Ottoman Empire known as “Greater Syria,” it has been conquered and ruled by a patchwork of successive powers: the Fatimid and Mamluk dynasties, with their centers in Egypt, and Frankish Crusaders. Lebanon was parceled off as a French mandate in 1923—touted as a haven for its Maronite Christian majority—and gained independence in 1943.

Characterized as a bridge between cultures and continents, Lebanon is unusually religiously diverse for any country, especially one in this region, but is in practice a chessboard of strained sectarian identities. It counts 18 official faiths and, until 2009, religion was listed on all Lebanese identification cards—information considered as essential as surname or date of birth. A balance of powers is maintained by constitutional law: the Lebanese president must be a Maronite, the prime minister a Sunni, and the speaker of the parliament a Shia.

This shaky coexistence was tested by a protracted civil war. In 1975, followers of the Christian Kataeb Party massacred 27 Palestinians in a Beirut suburb, sparking 15 years of fighting, during which a sniper-filled, militia-manned demarcation line divided West (Muslim) and East (Christian) Beirut. “In a lot of people’s heads, the war never ended,” says Ismael, a Shia Muslim with four sisters who all married Christians and converted. Years of conflict “compartmentalized the different religions,” he says. “It even divided Christians between each other, and Muslims between each other. It was like a crescendo.” The Order was particularly active during the civil war, which saw the construction of eight of its healthcare centers. “The beautiful thing that we do,” says Ismael, “is this cross goes everywhere. It reaches Druze, it reaches Muslims, it reaches Christians.”

Syria loomed large over the war in Lebanon, occupying the country during its duration and for another 15 years after—swept out, finally, during the popular Cedar Revolution of 2005. Syria’s own civil war broke out six years later. In 2011, poverty rates in Lebanon’s northern border areas already hovered at over a third, stretching the limits of Lebanese hospitality to migrants fleeing the war. It was another opening for the Order.

If nations are built on shared histories—imagined or real—then modern Lebanon might well be formed by shared traumas. Sudanese, Iraqi, Palestinian, Syrian: one in four people in Lebanon is now a refugee. As the Lebanese novelist Dominique Eddé has observed, “Every Lebanese invents a personal Lebanon for a country that does not exist.” The same is true of its borders, places of fluidity and flux that can be harsh or welcoming, depending on the circumstances under which one encounters—or reinvents—them.

At the height of their presence in the warring Holy Land, the Hospitallers maintained some 40 fortified outposts. A sprawling, fabled Crusader castle, the Krak des Chevaliers, was their largest, occupied from 1142 to 1271. Originally built by the Emir of Aleppo (though some accounts dispute this), it held an Order of Malta garrison of 2,000 troops and horses to fortify advancing Christian armies, with reserves of supplies lasting five years. According to the author Diana Darke’s account, skeletons uncovered in the castle’s ornate loggia were entombed with their shields and swords.

Sitting on a hilltop just five miles from the border where Syria meets Lebanon’s Akkar district, the castle became a base for rebel fighters traveling overland from Lebanon early in the Syrian war. The regime of Bashar al-Assad bombarded the UNESCO-listed castle in 2013, and cornered rebel forces blew up its medieval-era staircase, obliterating a Latin inscription on a window lintel from its crusader days: “Grace, wisdom and beauty you may enjoy but beware pride which alone can tarnish all the rest.” Today the fortress still towers, eroded and damaged but remarkably intact for now, over the village of Al-Hosn—Arabic for “fort.” And down in the village, there was, or perhaps still is, a stone house and vegetable garden—the ones that sisters Munira and Ghadire Abdelrahman once shared with their mother, and that they were forced to flee at the start of the war.

You can join the conversation about this and other Border/Lands stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook