How Boston Cream Pie Changed Americans’ Relationship With Chocolate

It was likely the country’s first cake made with cacao.

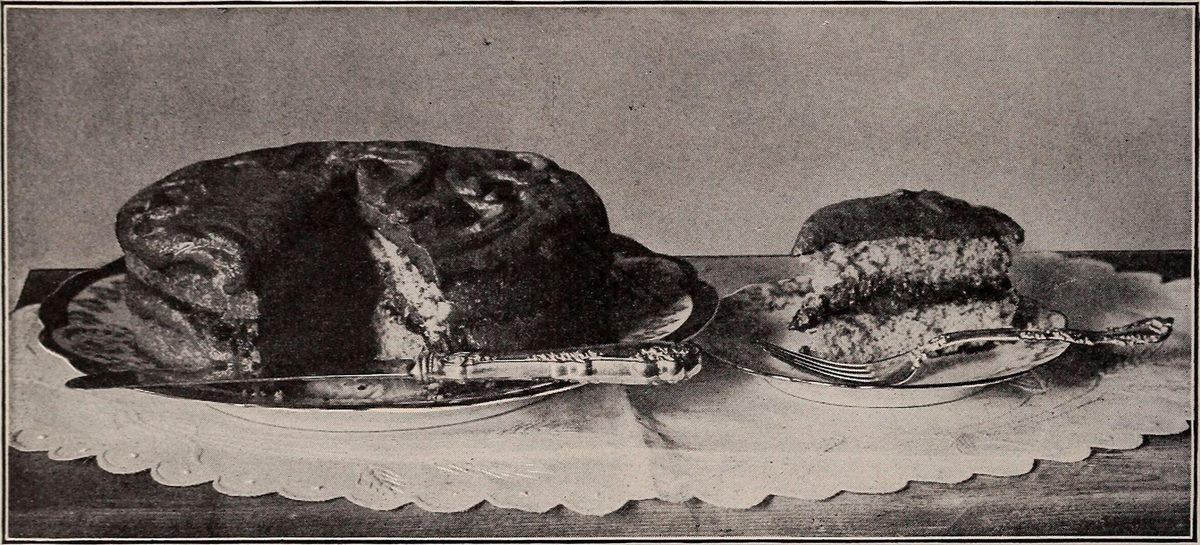

The Boston Cream Pie is a simple dessert: two golden sponge cakes with pastry cream between them and a thin layer of chocolate ganache on top. But the cake—and it’s definitely a cake, not a pie—has become so legendary during its more than 150-year history that it’s now the official state dessert of Massachusetts.

This makes the Boston Cream Pie something of an elder statesman of American dessert. It’s often made and served in the spirit of nostalgia and tradition, though some bakers create modern iterations, such as turning it into cupcakes and even ice cream. But while Boston Cream Pie now feels like a throwback, it was once groundbreaking. Because while the origins of the pie are a bit murky, we know the dessert was a pioneer, forever changing Americans’ relationship with chocolate.

Before the city gave its name to a cream pie, Boston was home to the United States’ first chocolate mill, Baker’s Chocolate Company, founded in 1764. The city had ready access to chocolate, which was a rarity in the country. But that doesn’t mean Bostonians were enjoying chocolate bars and truffles and cakes. Instead, they were sipping “drinking chocolate.”

“At least in the European and Colonial North American context,” says Dr. Carla Martin, Executive Director of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute and Lecturer at Harvard University, “people primarily consumed chocolate as a beverage.” As early as the 1670s, she says, Boston had a coffee and chocolate house where the mercantile class would go for a drink. By the 1700s, drinking chocolate had made its way into the kitchens of elite families, like those of Bostonians Benjamin Franklin, who grew up in the city, and Judge Samuel Sewall, who presided over the Salem Witch Trials.

Until relatively late in the 1800s, when better technology emerged, the only chocolate available was “crude circles that were gritty,” Martin explains. “You could see chunks of sugar particles in there. That’s the kind of thing you would need to prepare as a beverage because it wouldn’t be great for eating.” This was the state of chocolate in America when the Boston Cream Pie appeared on the scene.

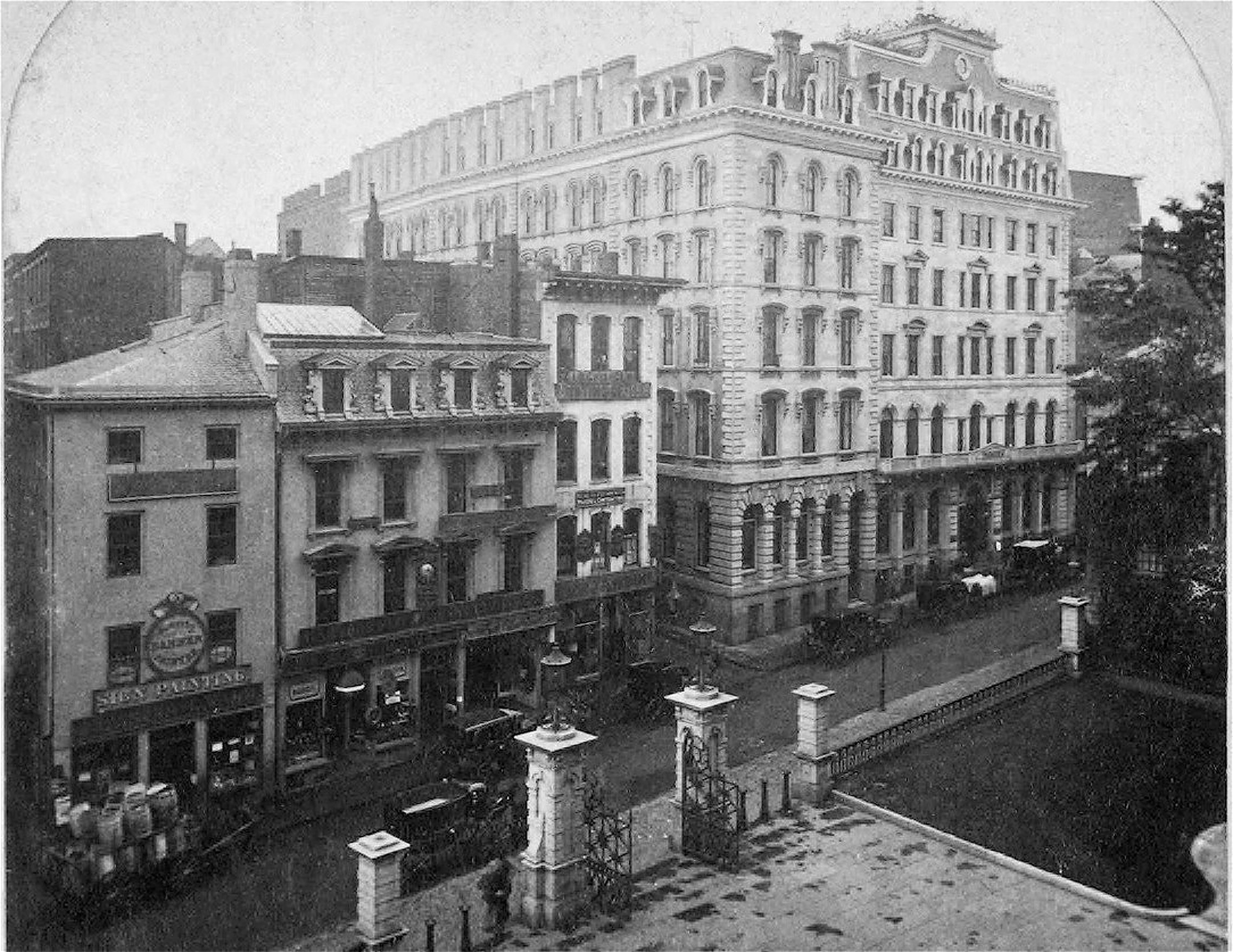

In 1855, Harvey Parker opened the Parker House Hotel just off Boston Common, the oldest city park in the United States. A former restaurateur, Parker envisioned a luxury epicurean experience, what Parker House historian Susan Wilson describes as “a hotel, a restaurant, and a destination.” At the time, there was an influx of tourism into Boston from both America and Europe.

Parker hired a French chef to lead the hotel’s culinary program, paying him $5,000 a year, roughly 10 times the going rate for a Boston chef at the time. Chef Augustine Francois Anezin joined the hotel staff in 1865 and set to work elevating the Parker House’s food. “A typical Parker’s banquet of the 1860s or ‘70s might include green turtle soup, ham in champagne sauce, vol au vent of oysters, filet of beef with mushrooms, roast mongrel goose, black-breast plover, charlotte russe, souffles au ris, mince pie, and a variety of fruits, nuts, and ice creams,” Wilson writes in her book Heaven, By Hotel Standards: The History of the Omni Parker House.

Another staple on the menu: one of the earliest known cakes with chocolate as an ingredient served in the United States. In other words, Boston Cream Pie.

Its appearance on the Parker House’s menu, under the culinary eye of Anezin, is the most common origin story of Boston Cream Pie. But it’s contested. “Every fact that I give you and every fact that you read will be contradicted somewhere,” says Wilson. Still, because the earliest known surviving menus from the hotel feature a version of the cake, she believes that this is when Boston Cream Pie was first served as the dessert we know today. “I never say they invented it,” she says, “I say they developed or perfected it.”

Parker House, which is now known as Omni Parker House and still serves Boston Cream Pie, can’t cleanly claim to have cleanly invented the dessert because similar recipes were circulating locally since Colonial times: Desserts like Washington Pie involve two sponge cakes with a custard or jelly filling, and sometimes a confection sprinkled on top. These desserts were called pies and not cakes, Wilson says, because home cooks made the cakes in the pie pans they had in their kitchens.

According to chef Peter Kelly, Associate Professor in the College of Food Innovation and Technology at Johnson & Wales University in nearby Providence, Rhode Island, there are many similar iterations of Boston Cream Pie’s basic premise. “I have a cookbook from around 1915 that doesn’t use the word Boston Cream Pie at all, but exactly describes the process,” he says. “It’s a derivative of this kind of pie, which is actually a cake with a filling. The third or fourth one down says Chocolate Cream Pie, but it’s actually a genoise with pastry filling inside and ganache on top.”

Wilson describes the Boston Cream Pie as “a direct descendant” of those Colonial progenitors. “If you look at old Parker House menus, you will see Washington Pie being served alongside Boston Cream Pie, or Boston Chocolate Cream Pie,” which are all essentially the same thing, with minor variations on filling and topping. Wilson points out that an 1887 cookbook, The Kitchen Companion by Maria Parloa, had a recipe for Chocolate Cream Pie that closely resembles our modern concept of Boston Cream Pie, and her cooking school was just around the corner from the hotel.

But to Megan Elias, Director of the Gastronomy Program at Boston University, the question of how the Boston Cream Pie was invented isn’t that important. Before the advent of celebrity chefs, recipe origins were hard to trace, as they evolved simultaneously in different places. Her students have researched the pie’s origins and come to the same murky conclusions. Instead, she is interested in why Boston Cream Pie became so influential.

“When someone makes something that other people want to eat, that’s when it enters into the common language,” she says. There often isn’t a good answer of where exactly a food came from. “The more interesting questions are the ones like, why does it matter to people? Why does Boston Cream Pie come to represent Boston, or New England, to people?”

A major reason was that Boston was, at the time, a culinary tastemaker for the country. “New England was a key space for that because it was such a cooking-focused area,” Wilson says. Parloa, who authored the 1887 cookbook with a Chocolate Cream Pie recipe, was one of the first directors of the Boston Cooking School. Along with the city’s other educational and communication resources—including farmers markets that featured baked goods, access to a major port, and the Parker House—it helped ideas like the Boston Cream Pie spread.

“Boston Cream Pie is late-19th century culture,” Elias says. “That food culture is a really specific moment.”

That moment included Boston seeding the idea across America of treating chocolate as not just a drink, but a common ingredient. The 1892 Fannie Farmer Cookbook, also known as The Boston Cooking School Cookbook, was revolutionary for its standardization of measurements in cooking, but also because it had recipes that called for chocolate as a pantry staple, an idea spread by the school’s Domestic Science and Home Economics classes as well. Martin describes the cookbook as pushing chocolate into “the public imagination.”

Despite its murky origins, the experts I spoke to agreed that the Boston Cream Pie was a pioneering dessert, and deserves credit for introducing Americans to a new way of using chocolate. Even if it wasn’t “the first,” it was still one of the first, and so popular that its history is still remembered and discussed.

In the decades that followed Boston Cream Pie, Massachusetts became such a center for chocolate production that it still has a “candy row” in Cambridge, where Tootsie Rolls are made close to Martin’s home. “It used to be the site of a dozen different chocolate companies,” she says. “On hot, humid summer days, it smells like Tootsie Rolls in my neighborhood.”

The legacy also lives on in New England’s sweets shops. “If you go anywhere on the coast, they have these little confectionery and fudge shops that are still so popular,” Martin says. “There’s this long tradition of coming off the beach and getting a piece of chocolate fudge. That stems back to the time when it really became a coastal tradition to have these kinds of chocolate-based sweets.”

America’s modern appetite for chocolate, she thinks, comes out of this history. “New Englanders continue to be deeply engaged with it, even if we’re not necessarily thinking about it.”

Original Boston Cream Pie

Recipe shared with permission of Omni Parker House

Sponge Cake

7 Eggs, separated

8oz. Sugar

1 Cup Flour

1 oz. Melted butter

Pastry Cream

1 tbsp. Butter

2 cups Milk

2 cups Light Cream

½ cup Sugar

3 ½ tbsp. Cornstarch

6 Eggs

1 tsp. Dark rum

Icing

5 oz. Fondant for white icing

6 oz. Fondant for chocolate icing

3 oz. Semi-sweet chocolate, melted

Substitution for Fondant Icing

Chocolate Icing

6 oz Semi-sweet chocolate, melted

2 oz. Warm water

White Icing

1 cup Sugar (Confectioner’s)

1 tsp. Corn syrup

1 tsp. Water

1. Separate egg yolks and whites into two separate bowls. Add ½ of the sugar to each bowl. Beat both until peaked. When stiff, fold the whites into the yolk mixture. Gradually add flour, mixing with a wooden spatula. Mix in the butter. Pour this mixture into a 10-inch greased cake pan. Bake at 350 degrees for about 20 minutes, or until spongy and golden. Remove from oven and allow to cool fully.

2. Bring to a boil in a saucepan the butter, milk and light cream. While this mixture is cooking, combine the sugar, cornstarch and eggs in a bowl and whip until ribbons form. When the cream, milk, butter mixture reaches the boiling point, whisk in the egg mixture and cook to boiling. Boil for one minute. Pour into a bowl and cover the surface with plastic wrap. Chill overnight if possible. When chilled, whisk to smooth out and flavor with 1 tsp. dark rum.

3. Level the sponge cake off at the top using a slicing knife. Cut the cake into two layers. Spread the flavored pastry cream over one layer. Top with the second cake layer. Reserve a small amount of the pastry cream to spread on sides to adhere to almonds.

4. For chocolate fondant: Warm 6 oz. of white fondant over boiling water to approximately 105 degrees. Add melted chocolate. Thin to spreading consistency with water. For white fondant: Warm 5 oz. of white fondant over boiling water to approximately 105 degrees. Thin with water if necessary. Place in a piping bag with a 1/8-inch tip.

Alternate: Melt the chocolate. Combine with warm water. Combine ingredients and warm to approximately 105 degrees. Adjust the consistency with water. It should flow freely from the pastry bag.

5. Spread a thin layer of chocolate fondant icing on the top of the cake. Follow immediately with spiral lines starting from the center of the cake, using the white fondant in the pastry bag. Score the white lines with the point of a paring knife, starting at the center and pulling outward to the edge. Spread sides of cake with a thin coating of the reserved pastry cream. Press on toasted almonds.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook