In Ontario, a Quest to Rediscover the Work of a Groundbreaking 19th-Century Botanist

Who is Catharine McGill Crooks, and what happened to her specimen collection?

In the spring of 1860, Catharine McGill Crooks paused on the banks of Mill Creek, in what is now Cambridge, Ontario, Canada. Pulling a narrow tool from her belt, Crooks lifted several stems of watercress (Nasturtium officinale) from the silty creek bed, before slipping them into a vasculum—a slim box outfitted with leather straps like a backpack. Later, she pressed these few, wet strands between sheets of heavy paper, before carefully mounting the dried plants with a solution of gum arabic and water.

Crooks repeated this process hundreds of times, preparing a sizable collection of award-winning specimens which were exhibited at home and abroad. Collecting rare native plants and introduced species alike, Crooks captured a valuable record of southwestern Ontario’s flora before industrialization, large-scale agriculture, and urban sprawl erased much of the region’s wild spaces forever. Yet despite her dedication and skill, these treasures have all but vanished.

Who is Catharine McGill Crooks, and what happened to her collection?

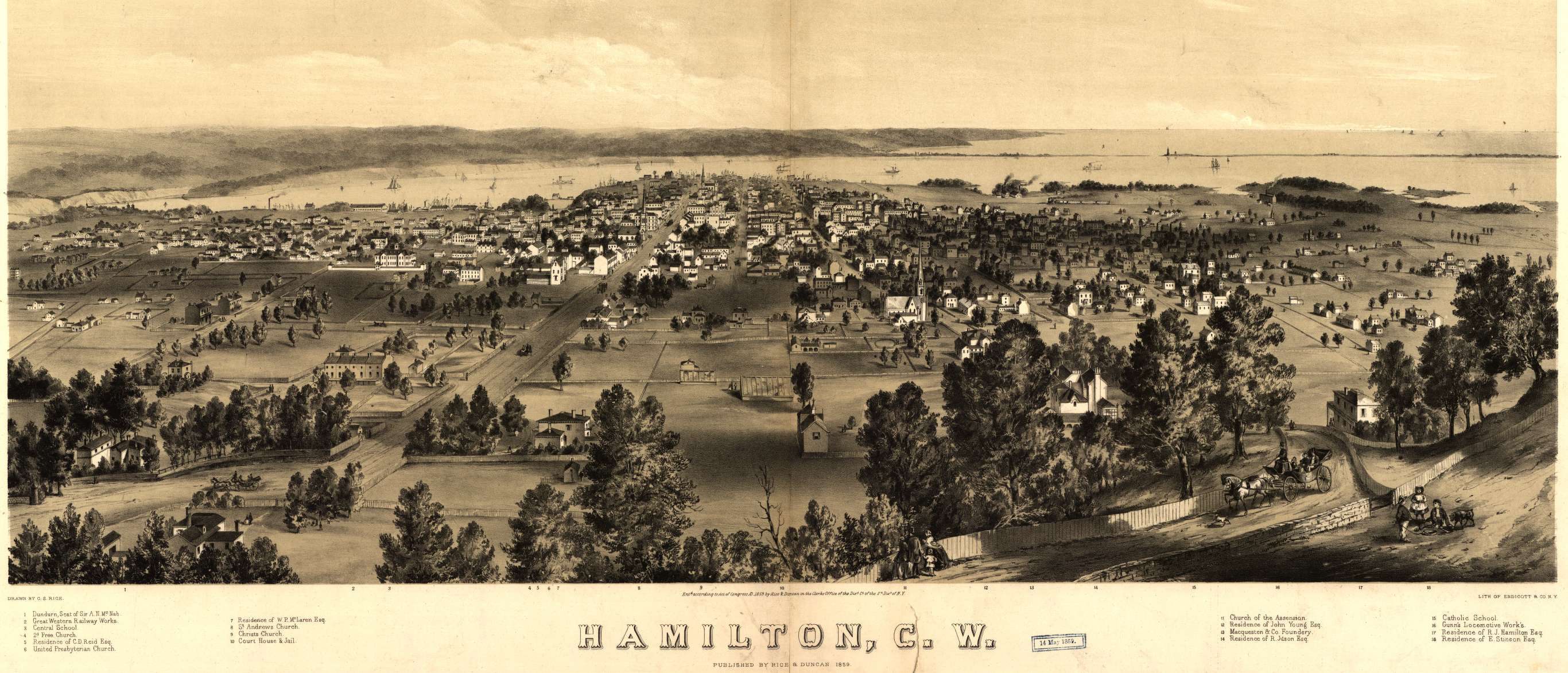

Traveling between the Canadian cities of London, St. Thomas, Hamilton, and Galt (now Cambridge), Crooks prepared roughly 500 sheets of dried botanical specimens, including plants collected in Hamilton by her brother-in-law Alexander Logie. Talented and ambitious, Crooks’s observations were cited in numerous publications, including the Geological Survey of Canada’s Catalogue of Canadian Plants—now considered the “ultimate in historic Canadian floras.” Posthumously described as “a most enthusiastic botanist,” Catharine Crooks—also known as Kate—fell into obscurity in the years following her death, leaving just a few tantalizing traces of her life and work.

Kate Crooks never achieved the reputation of the iconic Canadian author Catharine Parr Traill, whose 1885 book Studies of Plant Life in Canada was once called a triumph of nature writing. Nor is she as celebrated as Mary Delany, Beatrix Potter, and Anna Atkins, 18th- and 19th-century naturalists who skillfully merged their passions for art and science. Nonetheless, in the last years of pre-confederation Canada, Crooks’s work contributed to a burgeoning understanding of the Canadian flora.

Born in February 1833, Crooks was raised in Newark, Upper Canada (now Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario). Part of a large extended family of Scottish immigrants to Canada, Crooks was brought up by her mother and sisters after her father John, a postmaster and church elder, died of scarlet fever in March 1833.

As their mother’s health, too, began to fail, Crooks’s sisters turned the family home into a private school, educating local girls from prominent families. Margaret Crooks was just 16 when she formed the school with her younger sisters Mary and Susan. Having watched their late father teach a lively Sunday school, the girls were primed to follow in his footsteps. Kate and another sister, Augusta, were likely among their first pupils.

Little is known about the years that followed, until 1861, when Kate Crooks, then 28, joined the Botanical Society of Canada. Crooks identified over two dozen plants for her brother-in-law’s flora of Hamilton, including rare species such as Canada lily (Lilium canadense) and smooth false foxglove (Aureolaria flava). In the 1950s, Dr. Leslie Laking, then Director of Canada’s Royal Botanical Gardens at Burlington, Ontario, described the paper as “one of a few standard references for Ontario flora” at the time of its publication.

Crooks’s career reached new heights in 1862, when her collection of dried botanical specimens was displayed at the International Exhibition in London, England. She received an Honorable Mention for her work, which was exhibited alongside samples of Canadian wheat, wine, and forestry products.

Following the International Exhibition, several items from the Canadian display were donated to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, in London, England—but contemporary records indicate that Crooks’s work was not among these gifts.

So where are these specimens today?

I began my search with several databases specializing in biodiversity data—GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility), the Mid-Atlantic Herbaria Consortium, and Canadensys among them—but as a librarian, I know these tools have limits.

Every cataloguer has a to-do pile of items waiting to be catalogued. With this in mind, I also emailed herbarium curators in Canada and abroad, hoping I might uncover a lead. What followed was a litany of responses familiar to anyone working in memory institutions.

“Unfortunately, a very small percentage of the specimens in our collection have been catalogued,” replied one curator.

“None of Crooks’s specimens are in our database—of course, that doesn’t mean we don’t have any, but does make them very hard to find,” added another.

“Sorry I haven’t replied sooner. Lots going on and not enough people.”

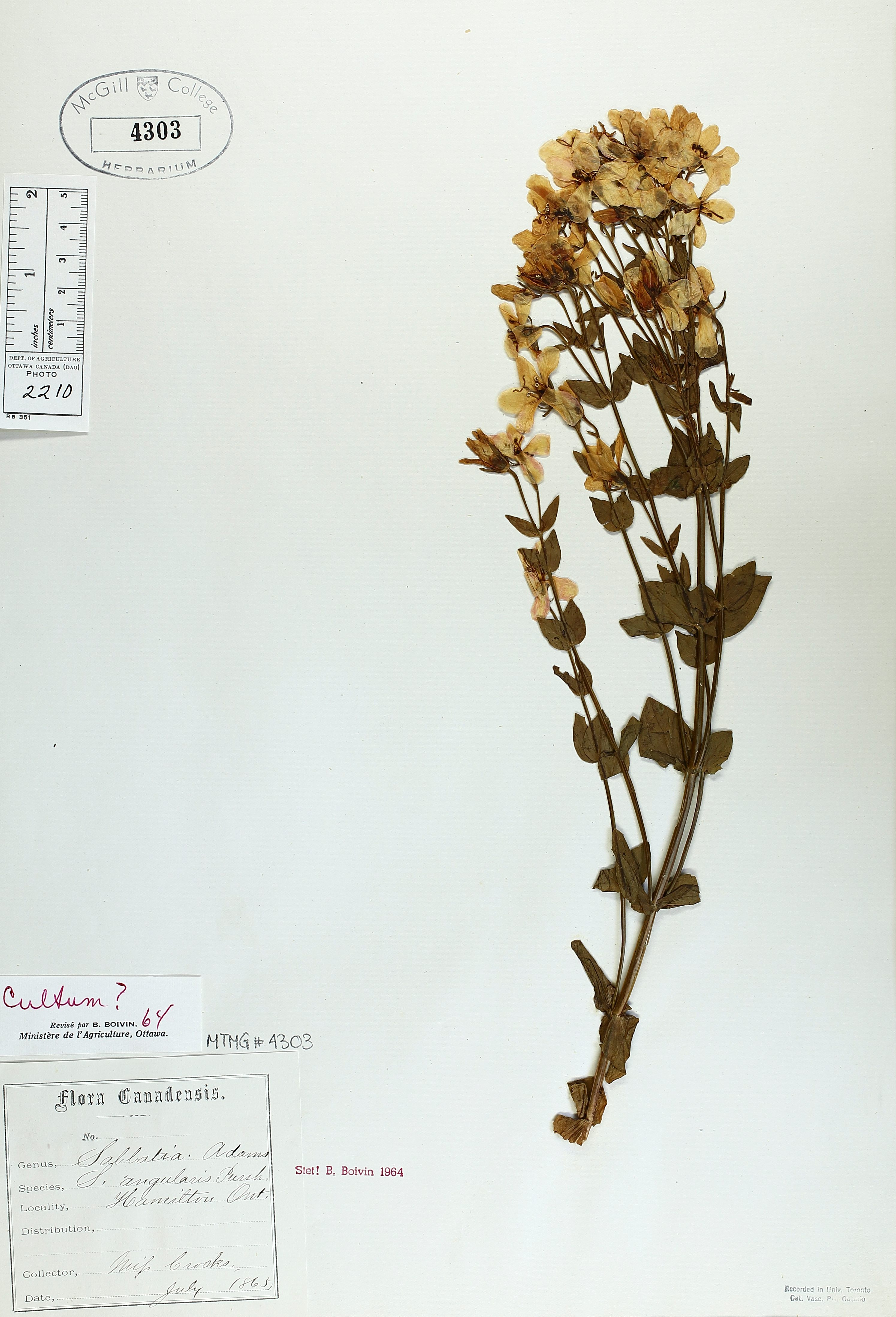

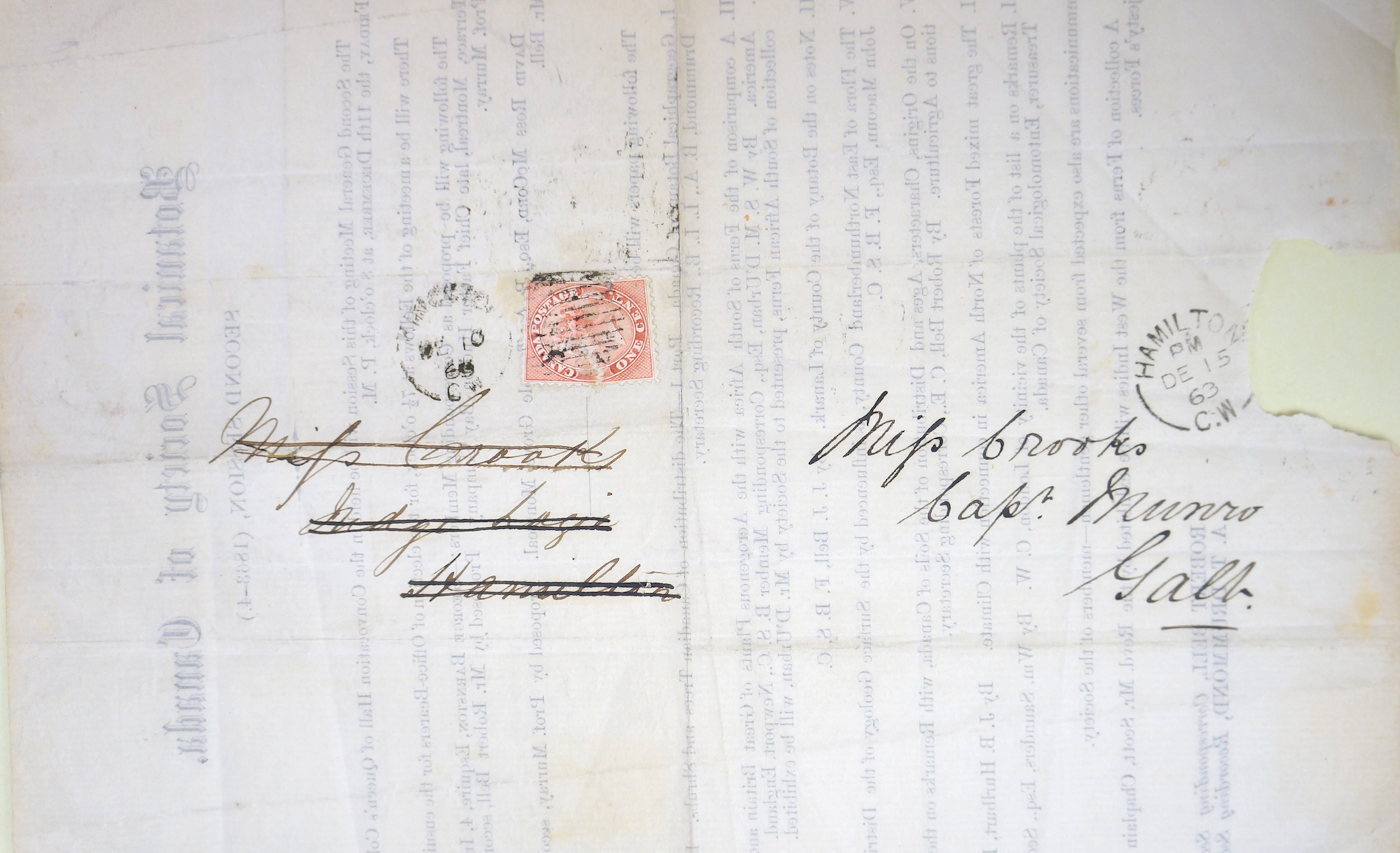

Finally, I received an email from Dr. Frieda Beauregard, curator of the McGill University Herbarium in Montreal, Quebec. Earlier, I had located a promising specimen held at McGill’s herbarium. Collected in 1865 by an M. Crooks, the date and surname matched. But who was M. Crooks? Dr. Beauregard’s email confirmed: The collector was not M. Crooks, but Miss Crooks.

Commonly known as rose pink, Sabatia angularis is an appealing wildflower native to North America. Rising to a height of one-and-a-half to two feet, on subtly angled stems, its star-shaped, pink blossoms carry five yellow stamens apiece. Its overall conservation status is considered secure, but rose pink is now endangered in the state of New York, and is considered locally extinct in Ontario.

In July 1865, a Miss Crooks—likely Kate Crooks—cut a single stem of rose pink in the city of Hamilton, roughly 40 miles west of Toronto. Today, this specimen is still the only documented collection of rose pink from the province of Ontario. Fixed to the page in a spray of pink-rimmed blossoms, it is likely the last botanical specimen Crooks prepared as Miss Crooks. The 32-year-old married William Lynn Smart, a British-born barrister, on July 3, 1865.

Crooks continued to work after her wedding, and in the autumn of 1866, she participated in the Provincial Agricultural Fair at Toronto’s Crystal Palace. As Mrs. Smart, her work was noted in the trade publication The Canada Farmer. “Mrs. Smart, of Yorkville, displayed… a very good collection of dried native plants. It was, of course, impossible to look through the whole of it, but in our brief examination we discovered some rare varieties which would gladden the heart of a botanist.”

Three weeks later, Crooks gave birth to her first child.

Crooks and her husband had three children in all, but like her father before her, she did not live to see them grow. In 1871, eight days after the birth of her son William Catharinus Gregory Smart, Crooks died in Toronto at the age of 38.

Forgotten as a botanist, Crooks left her mark on history in other ways. Shortly after her death, Crooks’s husband and young children were sued by three of her four sisters. All widows, they contested the terms of their sister’s will based on her status as a married woman. Crooks’s cousin Adam—a provincial legislator and Ontario’s Attorney General—leapt into action, drafting the Married Women’s Real Estate Act. Passed into Ontario law two years after his cousin’s death, the Act gave married women the right to open their own bank accounts, apply for life insurance, and dispose of their own property without a husband’s permission.

The Toronto Daily Mail mocked Adam Crooks, writing, “…for these, the first principles of revolution, the ‘strong-minded’ matron of a future day may teach her infants to lisp the name of Crooks.” While the historian Dr. Lori Chambers has observed that the Act was “a remedial measure intended for women’s protection, not their emancipation,” it is Kate Crooks, not Adam, who can be given full credit for these “first principles of revolution”.

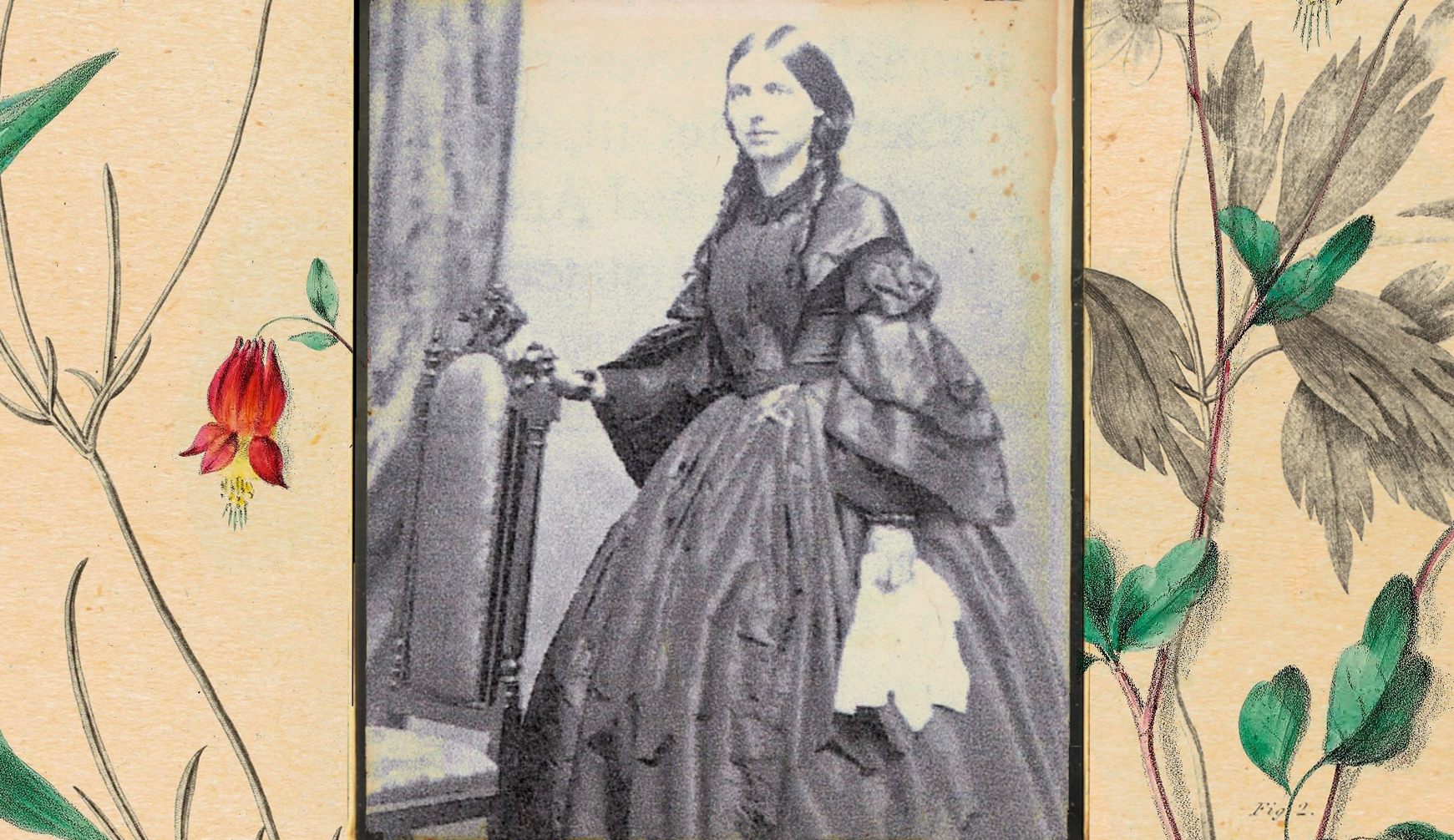

There is one known photograph of Catharine McGill Crooks. Shot in Hamilton by the daguerreotypist Robert Milne, Crooks stands tall against a brightly-lit backdrop. Her dress is voluminous—dark and bustled—while her hair tumbles in tight, shiny curls. Serene and self-possessed, she resembles a Victorian Mona Lisa.

Had she survived the birth of her third child, it’s not hard to imagine Crooks continuing her work once her children had grown. Inspired by Catharine Parr Traill, she might have written memoirs of life in the field. She might have explored photography or botanical illustration. Or she might have returned to the woods and meadows of her youth, building a new body of work in the process. While Crooks’s botanical observations offer a glimpse of the landscape around her, finding any more of her lost specimens would offer new opportunities for scientific and historical research. As Dr. Beauregard told me, plant specimens provide much stronger evidence than records based on observation alone. For now, a dormant legacy rests like seeds in the earth, waiting for the first days of spring.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook